Glencore was once billed as the Goldman Sachs of the commodities world. Back in 2011, the secretive Swiss firm listed here in London, going straight in to the FTSE 100.

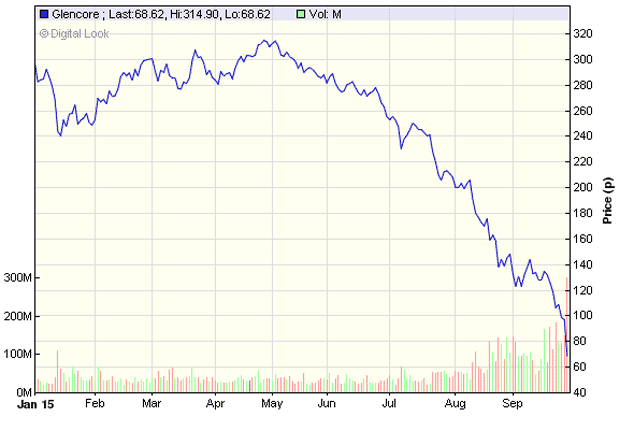

Since then it’s shed more than 85% of its value, as the chart below shows. What’s more, around 75% of that came since the start of this year. This is simply not what’s expected of a FTSE 100 company.

The stock plunged some 30% on Monday alone, following an analyst report suggesting Glencore could be worthless to shareholders. I’ve never seen a FTSE 100 company plunge in such a manner purely on the back of a broker’s note. When companies publish truly awful news, yes. But off the back of a broker’s note – a FTSE 100 blue chip? No chance.

So what’s going on?

Nigel Wilson, chief executive for Legal & General (a Glencore shareholder), said the mining company was facing a “quasi-Lehman moment”.

He refers to Lehman’s not-so-insignificant debt mountain that finally brought it down. Glencore’s acquisition of Xstrata in 2013 left a debt-pile stretching to £20bn. More seriously, £7.9bn of that is due to for refinancing before 2017. This could be a ticking timebomb.

As the price for insuring Glencore debt has risen, so the stock has fallen. But the release of Investec’s damning note undoubtedly brought a previously unthinkable scenario to a wider audience.

Investec suggests that the real reason for concern isn’t so much the real value of the debt, but the state of Glencore’s key commodity markets. Glencore has its finger in every commodities pie out there. If Glencore doesn’t mine the stuff, it’s trading in it. And if it’s not trading it, it’s probably worthless.

This is why it finds itself compared to the large merchant banks. And as with Lehman, if you’re holding a load of toxic junk when the markets turn down, then there could be big trouble ahead.

Friends in high places

The commodities business is highly cyclical. Boom and bust is par for the course. The share prices of the large mining giants ebb and flow accordingly. As demand in China has fallen, the mining sector’s share prices have drifted lower.

But in Glencore we have a behemoth that’s not only a miner, but banker/trader too. That puts it at risk of the interest rate cycle, as well as the commodities cycle.

The fear then is that if interest rates go up, there could be a whole world of trouble for Glencore.

It’s a textbook example of how even the greatest business minds can get carried away by the allure of debt. You see, as right as Glencore’s chief exec, Ivan Glasenberg, may have been about the interest-rate cycle, (ie rates have been pinned to the floor), it’s of little use if revenue plummets.

The capital value of Glencore’s mining projects are falling – and that puts its debt/equity value on a dangerously negative path.

Now, as it happens, Glasenberg has powerful allies, including several sovereign wealth funds. Indeed Glencore’s shares have bounced back somewhat since Monday’s heavy falls amid speculation that Glencore could raise funds through the sale of some of its divisions.

It’s worth remembering, that during the crisis, even the mighty Goldman tapped none other than Warren Buffett for help in shoring up its balance sheet.

Analysts at Citigroup have suggested that if Glencore’s share price remains at these levels, Glasenberg may well consider taking the firm private. Like I say, these boys have got friends in high places.

But as one looks to the wider economy, be it businesses or individuals, it’s hard not to notice similarities with Glencore’s drama. The only thing is, most people don’t have friends in high places.

What will mere mortals do when the tables turn?

Glencore’s debt trap is a classic example of misguided assumptions, not so much on debt, but on revenue. We see it time and time again in (admittedly) smaller quoted companies. This is why studying the balance sheet of small businesses is absolutely vital.

The balance sheet gives the company the financial backing to ride out revenue hiccups. And every business and individual needs a strong balance sheet, as revenues are always unpredictable. Too many investors get caught up in profit analysis, at the cost of balance sheet analysis.

Now, for a sector with both balance-sheet red flags hoisted, and misguided revenue assumptions, one need look no further than the good old buy-to-let market.

George Osborne, has already fired his first torpedo at buy-to-let investors. Restricting the amount of tax that can be offset against interest payments will probably not be the last move we see in this campaign.

After all, there are plenty of paper profits on the table. Encouraging landlords to get out of the game will release stock back to the market, thus delivering a few houses for potential voters. But it will also trigger capital gains and stamp duty – pretty handy for the UK Treasury’s coffers.

And considering what would happen to the landlord’s revenue stream should Corbyn’s Labour party win power, it’ll have many investors recalculating their revenue assumptions.

The point is, revenues are not within the control of Mr Glasenberg, and nor are they in the control of landlords – or anyone. Whether pushed by market forces or pulled by government intervention, it’s dangerous to assume a status quo. In an adverse market, only those with a strong balance sheet survive.

Who’s going to be there to bail out the ill-prepared? Have they got friends in high places?

Didn’t think so.