This week, restructuring firm Begbies Traynor reported that it had seen a 54% leap in the number of supermarket suppliers in financial distress. The argument goes that the effects of the supermarket price wars are being shoved down the line. So it’s the supermarket suppliers that suffer – they take the hit as the supermarkets try to cut prices while maintaining their margins.

Now I’d take a bit of issue with this. It’s undoubtedly a tough environment out there, but it’s also true that the supermarkets draw an unwarranted amount of this sort of criticism.

Many suppliers have been more than capable of getting themselves into their own scrapes. And judging by the performance of the many food suppliers quoted on the stock exchange, things really aren’t as bad as some like to make out.

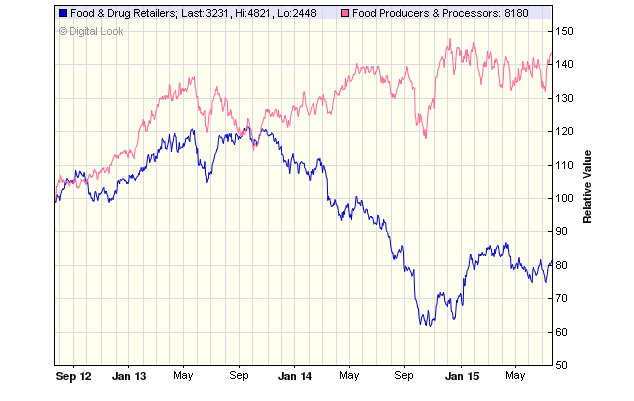

In fact, it looks like the travails of the grocery industry have fallen squarely on the shoulders of the major supermarkets. Take a look at the chart below.

Suppliers vs retailers over last three years

The pink line shows the stock market performance of the ‘food producers and processors’ over the last three years. Indexed to a base value of 100, the sector is now up some 40%.

The ‘food and drug retailers’ (blue line), tells a very different story. It’s down some 20% – that’s pretty poor, bearing in mind that stocks have been pretty bubbly over two of the last three years.

Now, I know that many people will tell me that my chart doesn’t tell the full story, and that specific suppliers have borne the brunt of the supermarkets’ malign intent – the dairy industry being the classic example.

But let’s take a moment to really consider what’s going on here. Are the supermarkets really asking suppliers to pay for their brutal marketing campaigns? A look at the realities of the dairy business suggests it’s a lot more complicated than that.

The supermarkets aren’t to blame for the dairy industry’s pain

The wholesale milk market is in a very strange place right now. Russia has refused imports from Europe (it’s tit-for-tat retaliation over sanctions), which means that the European market has seen a glut of the stuff – especially out of the Baltic states.

Earlier in the year, the Guardian reported that the wholesale price of milk had fallen to 16p per litre.

Now, that’s half the price that the major supermarket chains (including M&S, Tesco and Sainsbury) were paying British suppliers. At 32p a litre, the supermarkets are offering farmers around the cost of production. It’s not hugely generous, I agree – but for the farmers, it’s a ‘get out of jail’ card.

If some farmers have higher costs of production, perhaps as a result of investing in their facilities during earlier, more profitable years, then that can hardly be the fault of the supermarkets.

And if a supermarket decides to sell said milk as a loss-leader – at say 22p a litre – that’s entirely up to them. Headlines that scream “Milk being sold below the cost of production” and then infer that it’s the farmer who’s getting screwed here, miss the point. Loss-leaders are exactly that – it’s the supermarket taking the hit!

Look – I know that supermarkets ask suppliers to help to finance discounts and promotions, but this is evidently not the case when it comes to milk. The real problem for the dairy farmer is that he’s dealing with a ‘commodity’ product. As such, he’s open to rampant global competition.

Good business is about turning threats into opportunities

However, even with this huge competition, some people are still making it work. Only a couple of weeks ago, I was speaking to a local organic dairy farmer, who told me he’d just had his best year ever! As well as organic milk, he’s producing cream, cheeses and yoghurts.

In fact, given the changes in the retail industry, there’s never been a better time for small-scale producers to get out of the ‘commodity’ product business and into a genuine growth market – niche and local produce.

You don’t need me to tell you that consumer habits have changed remarkably over recent years. If the supermarkets are suffering, it’s because they haven’t evolved with the times. So I’m not proposing for a minute that we should feel sorry for them.

Online shopping and bulk shopping at discount chains such as Aldi and Lidl have developed relatively quickly. Faced with an oversupply of retail space, the supermarkets have battled it out on price. That’s history – but what’s important is the opportunity it’s opened up.

Much of the online and discount sector deals with bulky, boring, ambient produce (ambient is the term for non-fresh, or frozen).

But as it turns out, people are still willing to visit local shops, even on a daily basis, to fill up with fresh food. The modern punter, it seems, doesn’t know what they want to eat on Thursday, until Thursday rolls along. So, they get what they want, when they want it, and arguably, there’s less rotting food piling up in the nation’s fridges.

And supermarkets are responding to that shift. My Tesco Local (the convenience store) even stocks my old chum’s organic milk and cream. Perhaps this even marks a return to the traditional butcher, baker, and… er… Costa Coffee bar?

The point I’m making is that people are prepared to pay higher prices for a premium product, so long as it’s fresh, and easily available.

restructuring firm Begbies Traynor reported suggests it’s the average small-scale supplier that’s under financial stress. But these are exactly the same guys who should be evolving to accommodate the new, local and quality goods opportunity.

Of course it’s not easy making major transitions as this. But just as with the supermarkets, it’s the companies that are slowest to respond to changing habits that suffer the most.

So let’s not pretend that this is all the fault of the major supermarkets – after all, these are the guys who are really feeling the pain. The suppliers instead need to develop ways to capture niche and local markets.

My local organic farmer is working hard on the mail order side of things too. Funny – could it be that the online threat has turned into an opportunity for the canny producers?