Some spectacular failures have made outsourcing a dirty word. But the industry is here to stay, says Jonathan Compton.

Outsourcing in essence just means paying someone to do something that they can probably do better than you can. Most of us outscource our plumbing work, for example. It has, therefore, been around for a long time. But strangely, it only became recognised as a business strategy in 1989 – perhaps proving that consultants can be a little slow to spot trends.

The boom in outsourcing began in the 1980s, driven by a change in government policies, especially those of Margaret Thatcher in Britain. Since the end of World War II, the accepted wisdom had been that government was and should be responsible for an ever-wider range of economic activity, as owner, builder, manager, and operator. All radio, TV and telecommunications were government-owned and controlled. So too were power generators, railways, airlines, hospitals, coal mines, steel works, water supplies, education provision and parcel delivery.

Most of the car industry (British Leyland) and house building was government owned too; the private sector got the crumbs. In most of these businesses, even the most mundane operations, from cleaning windows to painting front doors, were carried out by state employees.

An objective Martian would have seen little operational difference in the management of the economies of the UK and the USSR.

The rise of privatisation

The break came in 1981, led in part by the Bank of England and the City. The telephone system was so dire that the City’s position as world-leading financial centre was at risk. So it was spun out of the Post Office, limited competition was introduced and privatisation followed. As ever, the decision was based on one simple thing: money. Privatisation took loss-making businesses off the national balance sheet. Better still, it raised considerable revenue for the exchequer while absolving government from responsibility for inefficiency and incompetence.

For the first time in two generations, people asked why government was involved in vast areas of activities that could be carried out by the private sector. Britain exported privatisation to the world, where it was seized upon by even rampantly socialist countries. In the aftermath, the private sector not only found that it suddenly owned highly lucrative cartels, with the consequent scope for excess profits, but started to look internally at its own organisation. In other words, they turned to a kind of privatisation of their own – “outsourcing”.

Outsourcing, as we have seen, just means using outside resources the better to perform activities traditionally carried out by employees internally. The theory is that a business should contract out non-core functions to cheaper specialists. Yet there is a subtle, albeit blurred, difference between “supply chain management” and true outsourcing. Toyota is an example of the former; it assembles and manufactures key parts of a vehicle, such as the engine, and sub-contracts specialist parts, such as the GPS navigation system.

Mistakes in such chains are inevitable, even at places such as Toyota, which is notorious for strong management of its suppliers. In October 2015 Toyota recalled 6.5 million cars because of a risk that faulty window switches could cause fires. This followed a ten million recall due to faulty air bags and, prior to that, nine million because of stuck pedal problems (later shown to be caused largely by drivers). Most of the faults lay with the sub-contractors.

True outsourcing

But true outsourcing today is most rampant in the dominant sector of all major economies (save China) – service industries. This sector has a big problem – it employs lots of people to carry out often mundane tasks, and people are expensive and unreliable. When I started in investment management, every firm had its own overstaffed department covering settlements, dealing rooms and primitive IT; they also had security guards, drivers, cleaners, librarians, report writers – and even dining rooms, all run by employees.

Most were expensive luxuries: for example, if there was little trading activity, then those in settlements and dealing rooms were twiddling their thumbs. As a result, most firms have passed these functions to third parties.

The way your money is managed today is an outstanding example of a virtual business. Apart from farming out the service operations, most research is copied from analysts at investment banks, or outsourced to third-party fund selectors, leaving your investment manager with the sole function of schmoozing current and new clients – better known as marketing. Fund-management balance sheets show this clearly – marketing costs are often the largest item of spending. Some now even outsource part of this to “customer service providers”.

The role of the crash and the internet

Two factors have accelerated the trend towards outsourcing: the internet, and the banking crash. The internet delivered pools of cheaper, often better-educated labour. Globally, India still ranks top for outsourcing, with six of its cities in the world’s top ten, but the Philippines has caught up fast – Manila now ranks second globally. In 2015, the “business process outsourcing” sector in the Philippines employed over a million people and enjoyed an estimated income of around $16bn, a tenfold increase in a decade. In the UK, outsourcing – from London especially – has made Dublin, Belfast and Glasgow numbers 12, 43 and 64 respectively in the world rankings. The reason?

The 2008 crash put huge strain on government budgets, driving more cost cutting and hence outsourcing. Britain’s welfare cuts caused much controversy, but the savings were minor compared with what was outsourced. Since 2010, the value of UK government work contracted out to the private sector has more than doubled to more than £90bn. It’s similar for other developed countries.

The downsides

Many outsourcing trade bodies produce robust papers on the value of the benefits they offer. In the main their insights are true. Outsourcers allow a firm to concentrate on what it does well. They also give access to the best specialists globally, who can neither be found nor funded internally. As with government privatisations, the key reason is money – to cut staff, thus costs, and improve profits. But there are downsides.

At the level of the whole economy, it has depressed wages. There has been much head scratching by central banks over the lack of inflation and growth in real (after-inflation) wages. Although weak commodity prices and competitive devaluations have played a part, globalisation and its symbiotic twin, outsourcing, have had the greater impact by cutting manufacturing and labour costs. Studies consistently show that workers in outsourcing businesses are paid substantially less than those they have replaced. It is a key reason why wages in the UK and developed countries have remained stubbornly flat, despite often reasonable growth and relatively strong employment.

Another downside is the outsourcers’ reputation for incompetence. I have long enjoyed an illicit thrill from financial disasters – and outsourcing provides many happy moments. The 2012 Olympics highlighted the incompetence of the world’s largest security firm, G4S. It proved hopeless at providing contracted personnel – the army had to be deployed instead. Prior to this fiasco, its overpaid CEO, Nick Buckles, had tried to take over ISS, the largest cleaning firm in the world, to create a global giant. Shareholders forced the deal to be aborted. Then, in 2014, G4S, along with the troubled Serco, lost a £400m monopoly contract on electronic tagging of criminals and were referred to the Serious Fraud Office.

Both companies were gouging the taxpayer, even charging for offenders who were dead. The information technology sector also provides a rich seam of outsourcing disasters. Since 2007, France’s Atos has failed to deliver even a fraction of its contract for the NHS patient record system and was lambasted by an all-party government committee late last year, especially for a cost-overrun from £14m to £40m.

This was dwarfed, though, by the heroic failure of the Universal Credit system introduced by the present government to rationalise welfare payments. The original estimate was a cost of £2.2bn; by the middle of last year less than 1% of all claimants had been enrolled. Estimated costs to date have exceeded £16bn. To spend £250 per head of population not to create a computer system is beyond ridicule. The four main initial providers were Accenture, BT, Hewlett-Packard and IBM. They continue to win outsourcing contracts. IBM also wins my gold medal for outsourcing disasters. Its health department payroll contract for Queensland, Australia, had projected costs of $6m in 2007. The final bill was 16,000% higher, at $1.2bn.

Surviving the fiascos

Despite these fiascos, though, outsourcing will remain a major growth industry. Occasionally, such as in 2012, it stalls, and there is a continual drip of firms taking back parts of their business from third parties (known as in-housing and on-shoring). Even a few government departments have taken operations back in-house to improve efficiency, for example, DVLA (issuer of driving licences), which had been outsourced for two decades.

Yet the trend is sure to continue for three main reasons. First, economic growth is likely to be muted for a prolonged period and government deficits remain high. Without strong growth and with ageing populations, costs must be cut – outsourcing is the least difficult solution. Second, in businesses, much outsourcing has become highly efficient (bill payments) and may be about to become more so (a revolution in how deliveries are made to customers is under way).

Firms frequently complain about the cost of the ever-rising tide of legislation: be it health, safety, food hygiene, or compliance. The obvious solution is to find a provider to ensure compliance rather than take on more employees. Finally, the disasters are not enough to reverse the trend. Major mistakes will happen, whether the work is outsourced or done internally – as every RBS customer discovered when its computers crashed in 2012.

In my own small businesses, it is inconceivable that we would run the payroll or basic bookkeeping; contract cleaners have proved more reliable and work faster; pensions, various computer and marketing functions, and hiring staff via agencies have all been more efficiently done by outsourcers than we could do ourselves. In short, outsourcing saves time, money and effort. Most importantly, when outsourcers fail, they can be fired at a minimal cost.

While every reader will have frothed with frustration at automated call centres or raged about sub-standard privatised national transport, these frustrations are insignificant when compared with the alternative – the huge waste of life spent waiting for government departments and bloated businesses to deliver services and goods at a reasonable price and on time.

The four stocks to invest in now

Outsourcing is a major growth industry, but with a serious structural flaw. When government departments or the private sector award contracts, they claim to give consideration to all stakeholders, with the priority being customer service.

In reality, the majority go to the lowest bidder. The outsourcers themselves make this problem worse. Friends and former employees from the UK’s largest outsourcer, Capita, tell a similar story. The policy is to win at any price, then work out how to squeeze the contract to make a profit. Hence the industry is plagued by loss-making deals with poor delivery, compounded by badly drafted contract terms. As a result, outsourcers tend to have long boom-bust cycles – large contract wins drive share prices up, but these deals often then turn sour. My hunch is that this will happen to Capita, and I cannot take G4S seriously – so I’d pass on two of the most popular shares in the sector.

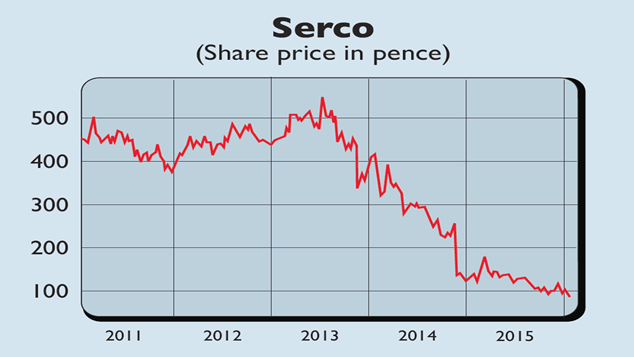

An outstanding example of the above behaviour is the once-mighty Serco (LSE: SRP), which has had a torrid two years, hence its share price falling from over 500p to 90p, taking the market cap to a five-year low of £1bn. Bad management and loss-making contracts globally resulted in an emergency rights issue last year, and no growth is expected in 2016. Moreover, the balance sheet remains stretched. However, the risk of bankruptcy has much diminished and loss-making contracts are being reduced by the new management team. This is led by Rupert Soames who enjoyed great success building up Aggreko and Misys. It is my favourite play in the sector, but is also the highest risk.

After the abortive bid by G4S, Denmark’s ISS (Copenhagen: ISS) finally listed in 2014. The market cap is £4.5bn, the prospective price/earnings ratio 15, and it has just started to pay dividends that should rise steadily. The core business is simple – office and industrial cleaning services – then there are various bolt-ons, such as catering, consulting, and emergency management services. ISS has a vast reach – somewhere very near you and in over 50 other countries, it has just cleaned a washroom. It’s a steady, if unspectacular, business.

Rentokil (LSE: RTO) is often dubbed “the Queen’s Rat Catcher” for its pest control services, but it is also involved in hygiene and heavy-duty workwear. Like so many outsourcing service companies, it almost went bust five years ago. But it has restructured, is steadily reducing debt, and is now expandingat a consistent and more sensible pace. Operating across 43 countries, it is growing both organically and through small acquisitions. The market cap is around £2bn, the forward multiple is 15, and it yields 2%.

Last year, in an article for MoneyWeek on defence, I suggested Babcock International Group (LSE: BAB). The share price has risen modestly and it appears that the period of missed targets is over. Babcock is the UK’s pre-eminent defence support contractor, whose operations include managing dockyards and other bases, trucks, fire fighting, computers and logistics. The Royal Navy is its largest client, but it has considerable business with other branches of the armed forces and similar significant business with foreign governments.

Modest but profitable contract wins have been accelerating recently. Defence spending is rising and so too will Babcock. The prospective multiple and yield this year are 13 times and 3% respectively. I think it is cheap and as safe as anything else around.

• Jonathan Compton spent 30 years in senior positions in fund management and stockbroking.