A new battery technology is being born – lithium – which could fuel big changes in mobile phones and cars. Buy the picks and shovels, says Bengt Saelensminde.

The biggest technology story so far this century has to be the huge growth in the use and sophistication of mobile devices. Yet incredible as it’s been, we could have had even more rapid growth and a far wider range of devices – but for one thing: batteries.

Smaller, better batteries

While batteries have improved incrementally over the years, they haven’t seen anything like the huge leaps seen in microchips, which are still doubling in power roughly every 18 months. The problem is that the basic battery design hasn’t changed since Sony released its rechargeable lithium-ion (li-ion) cell way back in 1991. The li-ion is a great battery – it powers most of our devices, as well as the burgeoning electric car industry. But you’re still talking about a technology that is nearly 30 years old.

It’s time the industry moved on. And move on it will. The technology behind the humble li-ion battery is on the cusp of revolution. A long-awaited second generation of li-ion cells will bring huge changes. With more powerful, longer-lasting batteries, we’ll see all manner of machines and gadgets shift away from using cables, or even combustion engines, and making the switch to battery power. We’ll see some big winners from this change. But among the biggest will be the companies who provide the basic raw material – lithium.

The whole battery question boils down to something called “energy density” – that is, how many free electrons (a battery is simply a store of electrons) you can pack into a given space. Cracking the energy density problem will inevitably lead to smaller, more powerful batteries. The biggest thing standing in the way of increased energy density today is what the technically minded call “parasitic elements” – ie, things that are in the battery, but don’t actually provide free electrons. The most significant parasite is the liquid solution in which the electrons are held – the electrolyte.

Huge corporations are working on ridding the li-ion cell of this type of electrolyte. For example, according to The Wall Street Journal, Google’s highly secretive Google X laboratory is working on a design for the next generation li-ion battery. But it’s far from the only one doing so. The key is to produce a “solid state” battery – where the electrolyte is solid, rather than liquid. These have a much higher energy density, and they’re safer too – liquid electrolyte li-ion batteries have been known to short-circuit and overheat, sometimes bursting into flames. And without liquid, the battery could become flexible, being designed into the product itself. That would be a big benefit for wearable technology, such as Google Glass, or the Apple Watch.

Google is developing all sorts of products that will depend on next-generation li-ion batteries. Drones that can fly around delivering things, or checking out travel information, or even assisting the police – they’ll all need a dependable, light, relatively cheap source of power. Google is also involved in health care (electronics within the body), robotics, and artificial intelligence, as well as plenty of conventional electronic equipment – all of which could do with a shot in the arm from better-performing batteries.

Arch-rival Apple has reportedly been poaching the best battery technologists in the world, leading to speculation that it’s set to make a move into electric vehicles. And even if it doesn’t, Apple has plenty of reason to be interested in batteries, simply for its current portfolio of products. It really doesn’t need to get into cars to justify investing in solid-state battery technology.

A breakthrough

The thing is, solid-state batteries do exist – but using current technology, it’s impractically expensive to build ones large enough to use for anything much beyond back-up power for microchips. The good news is that at least one firm – Michigan-based Sakti3 – reckons it’s cracked this problem, meaning that it’s hopefully just a matter of time before we see these new wonder-batteries on the market.

Without getting too technical, the company uses a process similar to that used to make computer chips – building the battery layer by layer using “thin-film deposition”. Sakti3 reckons it can build solid-state li-ion batteries at a cost of $100 per kilowatt hour. To put that into perspective, ‘old-school’ li-ion batteries cost around $500 per kilowatt hour, according to The Economist.

British technology giant Dyson – yes, the vacuum cleaner group – recently made a modest $15m investment in Sakti3, reports Christopher Mims in The Wall Street Journal. I say modest because, in reality, Sakti3 didn’t really want Dyson for its money. Instead, it’s the access to market that Dyson provides. Dyson wants to be one of the first companies to implement the solid-state li-ion batteries developed by Sakti3’s team of scientists.

As Dyson put it: “Sakti3 has achieved leaps in performance which current battery technology simply can’t. It’s these fundamental technologies – batteries, motors – that allow machines to work properly. The Sakti3 team has amazing ambitions, and their platform offers the potential for exponential performance gains that will supercharge the Dyson machines we know today.”

Look at the Sakti3 website and you’ll see the battery design work has already been done. Now it’s all about commercialisation and getting it into real products. That’s why it allowed Dyson to buy some equity in the business – it wants an investor who can bring products to market. The solid-state li-ion battery deals with the issues of size, weight, charge time, capacity and degradation (the number of recharge cycles possible before starting to lose charge).

In short, this battery tackles everything that users currently hate about mobile devices.

Booming demand

Better batteries will inspire greater demand for existing mobile devices. But more importantly, they will drive growth in products that aren’t yet largely battery powered. I’ve mentioned electric cars and drones.

But how about vacuum cleaners, mowers, and scooters? These are all items that can’t really cut the mustard with today’s batteries, but would benefit hugely from a power injection.

Earlier this year, electric-vehicle maker Tesla Motors updated investors with its latest suite of products. It has an obvious interest in better batteries: it takes the equivalent of 7,000 Panasonic laptop batteries to power a Tesla electric car. But it is also innovating in renewables. Powerwall widens Tesla’s business into battery manufacturing. The Powerwall promises to make renewable energy for households or small businesses a more realistic proposition. It is a mega-battery that makes it possible to store energy from solar, wind or waves, providing back-up power when the sun doesn’t shine. These pioneering efforts point to a very different energy future. When battery storage for renewables really takes off, demand will be huge.

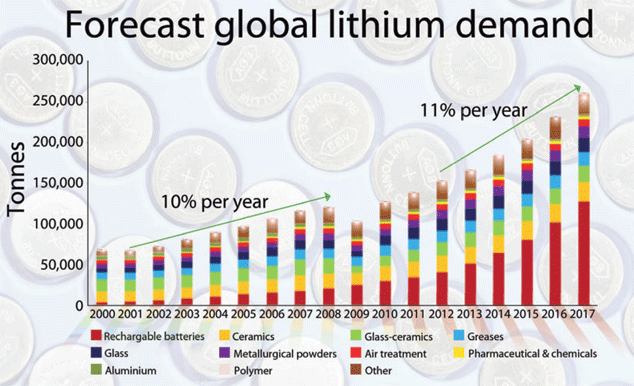

What this means is that industry projections for li-ion demand – and therefore for lithium – are woefully inadequate. The chart above, of projected demand for lithium, shows just how badly analysts are miscalculating growth in battery use. The red bars show how lithium use for rechargeable batteries has grown from next to nothing in 2000 to become the biggest source of demand right now. But the forward projection merely uses previous growth rates and extrapolates them forward. Few analysts are factoring in the huge new demand that’s set to come from the second generation of li-ion cells.

Tesla’s battery-making ‘gigafactory’ is set to come on stream in 2017, doubling production of li-ion batteries from today’s levels. And Tesla certainly isn’t alone. Other companies are working in this field too – we’re talking about battery production trebling or more in the next few years. This is huge.

In short, if you look at what’s happening in the battery-manufacturing industry – as opposed to what has happened over recent years – then you’ll see that analysts are making a big mistake. Or looked at another way, this could be a huge profit opportunity.

Innovations in mining

The other thing you can see from the chart is that there’s a vast range of uses for lithium, across the industrial spectrum (see below). Over the years, production has grown fast enough to satisfy demand, largely because of new extraction processes. Over the last 20 years or so, the industry has moved on from expensive and difficult hard-rock mining to extracting lithium from brines. These brines are largely found in South America and consist of huge inland lakes, known as salars, which have high levels of naturally occurring lithium. Brine from the salars is evaporated, leaving a cocktail of chemicals, including the highly prized lithium compounds.

It’s a big improvement on hard-rock extraction, but there is a downside – time. It takes about two years to complete the process. Even then, the climate can cause havoc – rain isn’t helpful when you’re looking to dry out an inland lake. So with demand for lithium set to grow on a scale we haven’t seen before, you might expect prices to rocket. Trouble is, that would be detrimental to the battery market – batteries need to be economic, as well as have great performance.

So the good news is that lithium mining has moved on. A new method is in the ascendency. It’s cheap, timely and can be scaled up to meet growing demand. As well as occurring in rock formations and in the salars, lithium is also known to exist within deposits of hectorite clay. Getting the metal out of the clay has proved tricky. But at least two junior miners believe they have cracked it – more on them below.

In short, the rechargeable battery market is in an incredible place right now. There’s a pervasive, growing demand for electricity storage – be it industrial and renewable, or for consumer devices.

A new battery technology is on the verge of being commercialised, ready to meet our ever-increasing demand for new gadgetry. Right at the same time, we have a whole new supply chain of lithium, the key element required to bring the whole thing together. I look at the best ways to play these changes below.

• Bengt Saelensminde worked in the City for several years before setting up his own business. He is now a freelance writer, entrepreneur and investor.

The three stocks to buy now

Over the years, the lithium market has developed into an oligopoly – that is, a handful of key suppliers have sewn up the market. As junior miners with lithium resources emerge, they’ve been gobbled up by the big boys. Lately, even the big boys have been consolidating. Last year, Albemarle Corp paid $6.2bn for Rockwood Holdings, the world’s largest lithium producer. But with the huge changes looming in the rechargeable battery sector, the dynamic of the market looks set to change. Well-funded firms such as Tesla and LG Chem won’t want to sit back and pay the oligopoly for their lithium – they’ll want a seat at the table. That could mean putting up the cash needed to put new clay extraction plants (see main story) into production. These are exciting times for the few junior miners at the coalface.

US-based, Canada-listed Western Lithium (TSE: WLC) has patented a process for extracting lithium from hectorite clay, and proved that it works in its demonstration plant in Germany. The company reckons it will be able to clear the lithium out of its Nevada clays at a similar speed to hard-rock mining, but with the cost base of brine extraction, the cheapest method.

London-listed Bacanora Minerals (Aim: BCN) – full disclosure: I own a small stake in this stock – stumbled on what seems to be a world-class lithium clay deposit in the Sonora region of northern Mexico almost by accident. It bought the mining rights for a borate prospect (another niche compound) from Rio Tinto, only to discover that it was sitting on huge deposits of lithium-rich hectorite clay. With these sorts of deposits starting to become of commercial interest, it partnered up with another London-listed company, Rare Earth Minerals (Aim: REM), which has funded a programme of exploratory drilling that has unearthed billions of dollars’ worth of lithium in the hills of the Sonora region.

Of course, the question is – can it recover the lithium cheaply enough? Over the years, Bacanora has developed a lab-based extraction method. The company chairman (and veteran of the junior mining sector) Colin Orr-Ewing has let it be known that the company’s unique methods of metal extraction is both environmentally sympathetic and can even beat brine extraction on costs. Rather than use nasty chemicals to extract the lithium, Orr-Ewing says the process is a relatively simple one involving roasting the clay, then leaching the lithium compounds out with water. Given environmental regulations in the car industry, such concerns could be a significant factor when choosing a supplier.

The huge battery corporations require secure and scalable supply. Both Western Lithium and Bacanora say they can deliver. What they need is the money to put their laboratory-based models into full-scale production. Both are looking for partners who will fund construction of plant and facilities,in order to secure future supply. I have researched the lithium market, and it’s my view that both miners can get these deals done.

Don’t get me wrong – these are still highly speculative investments. All junior miners and explorers must be considered punts. Remember, there’s no production yet, lots of things can go wrong, and these tips are for your speculative money only. But this is also an industry in a state of flux. So getting in early could be hugely profitable – just don’t bet the house on it.

You might instead consider Rare Earth Minerals as a slightly more diversified play – it’s a holding firm investing in both rare-earth mineral projects and lithium (not technically a rare-earth), and has big stakes in both Bacanora and Western Lithium. Another company to keep an eye on is European Lithium – it’s not yet listed, but plans to raise £5m on Aim later this year to develop a project in Austria.

What is lithium?

Think back to your school chemistry lab. Remember the lesson where a piece of metal got dropped in a flask of water and it started fizzing? This may have been your first introduction to lithium. It is a soft silver in colour, and it’s the lightest known metal. In nature, lithium is only found in compounds (in subtances where it is joined to other elements, in other words) and often occurs in sea water, which is why a common way to extract it is from brines. It was first discovered in 1817 in the mineral petalite. Commercial lithium is extracted electrolytically from lithium chloride and potassium chloride.

It has a number of uses beyond batteries. It is often used in alloys with aluminium, copper and cadmium to produce strong, lightweight materials for the aircraft industry, as well as in heat-resistant ceramics and mirrors. It is also used in lithium grease lubricants and as an additive in the production of steel, iron and aluminium. It was the transmutation of lithium atoms into helium that formed the first man-made nuclear reaction in 1932, while lithium-6 deuteride is used to fuel thermonuclear weapons. The metal also occurs naturally in plants, animals and the human body and has been used since the 19th century to treat bi-polar disorder. While it is not rare, it can be difficult to mine because concentrations are often too low, making extraction onerous and expensive. America once dominated production, but now 60% of mining takes place in South America, with 30% in Australia and China.

Six ways to invest in the batteries of the future

By Piper Terrett

We can’t know exactly which next-generation battery technology will triumph, but it’s clear that demand for better batteries will just keep growing. So as well as keeping an eye on lithium producers, it’s worth watching the battery manufacturing sector too.

One of the biggest and best-known players is Nasdaq-quoted Tesla (Nasdaq: TSLA). While it earned its reputation as an electric car maker, it is creating a stir with its recently launched Powerwall home storage and industrial Powerpack mega batteries. In recent first-quarter results, the firm said that response to the launch had been “extremely positive” and that the potential market is “enormous” and easier to scale up globally than car sales.

Since March, the share price of the “Apple of autos” has recovered from a low of $181 to hit $256. However, Tesla notched up a $154m loss in the first quarter alone, and the shares trade on an astronomical forward price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 240. Bloomberg consensus forecasts put the shares on a price target of $274, so there could be some upside for the brave – but despite its high profile, it’s arguably as much of a punt as the lithium miners mentioned below.

Another car manufacturer getting in on the action is German-listed Daimler (Frankfurt: DAI). The firm recently announced its move into the energy storage sector via subsidiary Deutsche ACCUmotive. Having worked on the technology since 2009, its first lithium-ion unit is already online and it is targeting the industrial, business and domestic markets. The subsidiary already makes batteries for the hybrid and electric Mercedes-Benz. Daimler says its Mercedes-Benz energy storage units will be available for order this summer.

This is only a small part of Daimler’s business and it will be some time before it materially contributes to the bottom line, but otherwise the company is in decent shape. First-quarter sales of Mercedes-Benz cars and Daimler trucks were solid and analysts at broker Natixis upgraded their price target from €91 to€100. A French crackdown on diesel cars is a worry, but the forward p/e of 11.2 looks reasonable.

Two major firms producing lithium-ion batteries are Samsung SDI and LG Chem. Both are listed in South Korea, but have London International listings. You could get exposure to Samsung by buying an exchange-traded fund – one possibility is the Vanguard FTSE Asia Pacific ex Japan ETF (LSE: VAPX) – or consider the iShares MSCI South Korea ETF (NYSE: EWY), which invests in both companies. But neither are pure plays on the sector, so they’re not the best way in.

In Japan, Sony Corporation (Tokyo: 6758) is another big player. After a decent run, the shares have dropped back. They trade on a current p/e of 25, falling to 20 for next year, which, while not cheap, is relatively fair compared with its peers in the electronics sector. Analysts were upbeat about a recent investor day held by the corporation.

Lastly, American firm EnerSys (NYSE: ENS) may be worth a look. The international battery manufacturer and distributor recently posted record fourth-quarter results. It services the aerospace and defence sectors and is developing its own lithium-ion batteries. The shares trade on a forward p/e of 15.