Recent months have seen some spectacular moves in foreign-exchange (forex) markets. Switzerland’s shock decision to abandon its peg to the euro in January saw the Swiss franc surge almost 30% against the euro in a day. And the US dollar has risen 15% over the past six months against a basket of its major trading partners.

So it’s no surprise that investors are more worried about how exchange-rate moves can affect their returns – and that’s driving a mini-boom in funds that hedge their currency exposure.

There’s now $60bn invested in currency-hedged exchange-traded funds (ETFs), according to data from BlackRock, the manager of the iShares ETF range, up from just $10bn at the end of 2012. Over $13bn went into these funds in the first two months of this year alone. But does it make sense to hedge your currency exposure, or is it likely to result in lower returns?

Taking a view on currencies

The most obvious reason we might choose to use a currency hedge is because we have a strong opinion on what a currency is likely to do. Imagine that we plan to buy Japanese stocks because we think that the Bank of Japan’s quantitative easing (QE) policies will help to boost the stockmarket. However, we also believe that QE will cause the yen to weaken.

So we invest using an exchange-traded fund (ETF) that hedges its yen exposure. Let’s assume that the Japanese market then goes up 10%, while the yen weakens 5%. Our currency-hedged investment gives us a return of 10% in sterling terms, while an investor who didn’t hedge would only gain 4.5% – so deciding to hedge has meant larger profits. Of course, if the market had dropped 10%, while the yen gained 5% instead, we wouldn’t have had the benefit of the strong yen trimming our losses – so this can work both ways.

The important point here is that we are consciously taking a view on the direction of the currency – that the yen will get weaker – and we’re looking to incorporate that view in our investment decision. Of course, predicting currency movements is more a matter of luck than judgement and we stand a good chance of being wrong. But if we’re confident in our forecast, currency hedging here is more consistent with our overall investment view than not hedging. Conversely, if we expected the yen to strengthen for whatever reason, it would be more consistent not to hedge.

Avoiding the unexpected

However, this scenario is quite unusual. We often won’t have a strong conviction about the outlook for a specific currency. Yet we know from history that exchange rates can have a large impact on returns over time. For example, from 2002 to 2007, when the pound was strengthening against the dollar, the S&P 500 returned 67% in US dollar terms, but 36% in sterling terms. Over the next five years after the pound peaked, the opposite happened: the S&P 500 lost 3% in US dollar terms, but still showed a profit of 19% in sterling terms. Given that, we might want to hedge simply to reduce the risk of unpredictable losses from currency moves. By doing so, we give up the equally unpredictable possibility of currency gains. And we will incur expenses: currency hedging costs money, even if the impact should be minimised when investing in a fund that can use low-cost ways of hedging. But we may feel that the reduced risk makes this worthwhile.

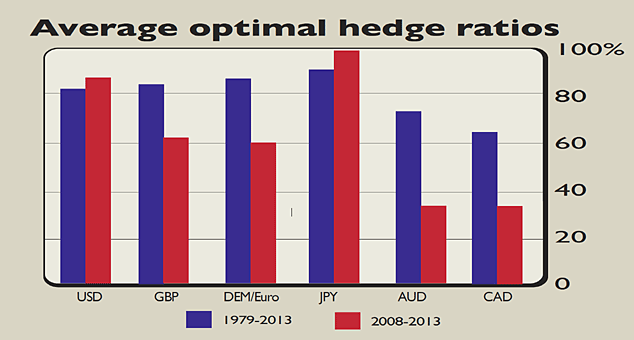

Whether hedging turns out to be beneficial will only be obvious in hindsight. But a recent paper* by Sanne de Boer of QS Investors (part of US fund group Legg Mason) offers a fairly comprehensive test of the impact over the last few decades. De Boer looked at the outcome from hedging stocks across six currencies between 1979 and 2013. She found that hedging slightly reduced long-term returns, but improved risk-adjusted returns as measured by the Sharpe ratio (returns relative to volatility). This implies that if it’s important to protect our capital during times of market turmoil, hedging is the way to go. If we can stomach the ups and downs, choosing not to hedge should give us higher returns.

Selective hedging

However, there are some nuances to this. Hedging all foreign-currency exposure did not always give the best trade-off between risk and return. The ideal hedge ratio varied depending on the investor’s home country and the country they were investing in. The more cyclical their currency was – meaning the more it tended to rise and fall in line with global stockmarkets – the smaller the benefit from currency hedging. That’s because exchange-rate movements can provide a natural hedge for countries with cyclical currencies (if our home currency tends to weakens as global stocks fall, it helps cut the losses on our foreign holdings).

So an investor who wants to balance risk and return should hedge selectively. For example, from 2008 to 2013 a UK investor who held equal amounts of the other five countries in the study would have done best by hedging around 60% of their exposure, as the chart above shows. However, that would have consisted of hedging all their Australian and Canadian holdings, most of their European exposure, but almost none of their US positions. A Japanese investor did best hedging almost everything, while an Australian should have done relatively little hedging – mostly of other cyclical currencies, such as the Canadian dollar. As the chart illustrates, the optimal hedge ratio changes over time, so the exact numbers may not be a perfect guide to the future. But the broad principle of hedging currencies that are more cyclical than your own seems to be a useful rule of thumb.

*Smart currency hedging for smart beta global equities, Sanne de Boer, October 2014, qsinvestors.com