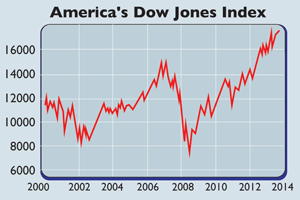

American stocks have hit new records amid more upbeat economic data. More than 200,000 jobs were added to payrolls in June, the fifth month in a row of solid gains. The unemployment rate, now 6.1%, fell to a six-year low. But things might get trickier from here on in.

As the economy improves, the end of money printing – followed by interest-rate rises – draws nearer. And the withdrawal of central-bank stimulus could give markets a nasty jolt.

History suggests that after some initial jitters, equities cope reasonably well with tighter monetary policy. Interest-rate hikes may temper growth, but rising rates also mean that an economy is deemed strong enough for the central bank to fret about pre-empting inflation. But this tightening cycle could be different.

For starters, the level of central-bank help has been unprecedented. In the past seven years, global policymakers have cut interest rates 567 times and injected $14trn of liquidity into markets, says Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Fifty-six per cent “of the entire world lives under the spell of zero interest rates”.

“Perfectly judging a retreat from these exceptional policies is not possible,” says John Authers in the Financial Times. Events in the US tend to set the tone for world markets, and “it is a given” that the US Federal Reserve will make a mistake.

The only real question mark is over what type of mistake the Fed will make: will it tighten too soon, damaging fragile growth, or will it err in the other direction, leaving rate hikes too late?

Doing nothing will just encourage more bubbles to form, creating another crisis when they burst. It could also allow inflation to get out of control, meaning the Fed would eventually have to raise rates more rapidly than it had hoped.

That could hammer growth. That’s because economies are unusually vulnerable to rate hikes this time round. Debt loads have barely fallen since 2007, says Buttonwood in The Economist.

The debt has merely been “shuffled around” from the private sector to the government. And in America, companies have taken on more debt again, with corporate borrowing at a record. Rock-bottom rates have allowed debtors “to scrape by”.

But “it is far from clear that debtors could handle interest rates that would have been classed in the past as normal – say 3%-4% – or indeed that governments would welcome bond yields of that level”. Whatever happens, it’s hard to see markets being weaned off liquidity without some serious turbulence.