German house prices have finally started to rise. Housebuilders and furniture makers are set to benefit, says Matthew Partridge.

Property markets around the world were hit hard by the financial crisis. But one area has suffered more than most – the eurozone. With sovereign debt a huge problem, and the European Central Bank unwilling to print money as freely as central banks in America and Britain, prices in some countries have cratered and have yet to really recover. In Greece, prices dipped by 18%. In Spain, it’s 19%. Lithuanian prices fell by 28%, prices in Estonia are down 34% and in Ireland prices have pretty much halved, according to EU data. Even nations such as France and Italy, which have avoided an all-out crash, have still seen prices fall in ‘real’ (inflation-adjusted) terms.

As if seeing the price of their house tumble wasn’t enough, homeowners are bearing the brunt of efforts to balance the budget. France has raised both the level of property taxes and the length of time that people have to hold onto their house before it becomes exempt from capital-gains tax. Spain has stepped up fines for evading planning regulations. And Greece is using property as a tool to identify potential tax evaders. While this makes fiscal sense – property can’t be hidden away or dragged across the border – it doesn’t bode well for a rapid recovery.

However, there’s one European property market that looks decidedly healthier: Germany’s. The main problem with the eurozone has always been that having one key interest rate shared by so many different countries means that monetary policy will always be too loose for some, and too tight for others. When the euro first came into use, more than a decade ago, countries that are suffering today, such as Ireland and Spain, were growing rapidly. Interest rates were too low for these countries, which is why they had such epic property booms and busts.

For Germany, on the other hand, still struggling after the reunification of east and west, interest rates were – if anything – too high. That made the early years of euro membership tough. But it also meant that the housing insanity that engulfed many of the eurozone’s other capitals didn’t take hold in Berlin. So while Germany didn’t enjoy a property boom during the pre-credit crunch years, it hasn’t suffered a bust either.

And now the positions are reversed. The German economy is now the strong one, while the rest of the eurozone languishes in or near recession. Interest rates that were once too high for Germany are now arguably too low. With fears over inflation growing, German house prices have finally started to rise. The market in Berlin has been especially strong: German economic think tank the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) reckons prices for flats have risen by as much as 70% since 2007, while the time needed to sell property in the German capital has halved to three months. But it’s not just a regional phenomenon; the popular Eurospace property index suggests that national prices are up by 8.5% over the past year.

That sounds like it’s just another high-risk bubble – until you realise that this boom has a long way to go before German property actually becomes expensive. In many parts of Germany, including Berlin, prices remain lower than the rebuild cost (in other words, you can buy for less than it would cost you to build the same property, a good indication of value). As M&G points out, German property prices have barely moved in nominal terms since 1990 and reunification. “The recent increases in house prices at the national level and in cities like Berlin have started from a very low base, and there is significant potential for further increases.”

Germany remains cheap by historical standards, with the ratio of house prices to incomes about 20% below its long-term average. And if you look at house prices in relation to rents, the undervaluation is even greater. Of the major global housing markets, only Japan looks better value.

Now, you could go and buy a property in Germany. But while it’s certainly an option, it’s not the most practical one for most people. Buying a single property is an illiquid, undiversified investment. Unless you have a specific use for the property – as a holiday home, or pied á terre – there are easier ways to profit from the German property boom.

First, you can buy shares in a property investment company or a real-estate investment trust (Reit). Secondly, you can buy shares in the companies that build houses (or in some cases manufacture them). And finally, since new houses usually mean new fittings (think fresh bathrooms and kitchens), the future looks bright for companies that make furniture and sell do-it-yourself materials.

Incentives to become a landlord

Until recently, a defining feature of the German property investment market was the fact that existing tenancies were subject to strict rent controls, limiting annual price rises. This is great for tenants – rents in Germany are lower than in most other major European cities. It also means German home ownership levels are relatively low – only about half the population owns the house they live in, compared to an average of around 70% Europe-wide, according to M&G. But rent controls have also limited the supply of housing (if landlords can’t raise the rent, there’s less incentive to be a landlord). The main German landlord association thinks there is a shortage of 250,000 apartments.

The powerful tenants’ lobby makes radical change unlikely. But there are signs that controls might be loosened. New laws passed in 2012 allow landlords to raise rents by up to 11% a year, as long as they carry out undefined ‘improvements’: a loophole that has been eagerly exploited. Higher rents, along with cheap prices, have drawn a steady stream of overseas buyers, who now account for just under a third of sales. But while the costs of buying and selling are relatively low, German banks are quite conservative, typically limiting loans to two-thirds of the value of a property. This means individuals must be cash rich if they want to enter the market.

However, banks are far more willing to lend to companies and trusts. And because both Germany and German property are seen as secure, low-risk investments, they can take advantage of rock-bottom interest rates. Since property firms make most of their profits (excluding capital gains) on the difference between the rental yield and the cost of borrowing, this is good news for them. Borrowing more allows them to boost their returns on equity (although it also increases the company’s vulnerability to any downturn).

The amount of money flowing into the market may also encourage a wave of mergers and acquisitions – for now, the industry is extremely fragmented. Merging some of the major investment companies would allow them to share resources and cut costs in areas such as marketing and management.

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

If you’re interested in buying gold, our up-to-date directory of the foremost gold brokers and ETF funds makes essential reading.

Compare the UK’s leading gold brokers

The kit-home revolution

However, housebuilders are likely to enjoy the biggest boost from the German boom. In the early 1990s, reunification drove a burst of investment in housing. But much of the housing stock remains poor quality, particularly in eastern Germany, where cramped pre-World War II housing is common. This means there’s plenty of demand for new homes, and housebuilders are getting busy again. Nearly 100,000 permits for building new houses were issued in the last year, according to Danske Bank. That’s up more than 50% from the late 2009 trough. Construction’s share of German GDP has also risen to levels not seen since 2000. Official forecasts suggest this growth will continue throughout 2013.

One particular beneficiary has been the prefabricated-homes industry (sometimes called ‘kit homes’ or ‘flat-pack homes’). In most countries, prefabs are viewed with suspicion, if not outright disdain. In Britain, they will forever be associated with the low-quality dwellings knocked up in the late 1940s and 1950s, to deal with the post-war shortage.

Until a decade ago, a similar stigma existed in Germany. But German firms have used advances in technology and design to produce prefab accommodation the equal of any ‘normal’ house. These ‘next-generation’ prefabs have several advantages over traditional building methods: they can be assembled very quickly, with the exterior put together in less than two days; and because they are made from scratch using computer-aided design, each house can be customised.

‘Luxury prefabs’ are environmentally friendly too. The materials and design can be tweaked to maximise the sunlight allowed in and minimise the heat that escapes. This saves so much energy that some German flat packs are ‘passive homes’ – needing little or no extra heating, even in the depths of winter. As a result, German prefabs have grown in popularity beyond Germany too. While the main overseas markets are Switzerland, France and Italy, firms are establishing small footholds in America and Australia. The Huf Haus design has won a following in Britain, with its homes profiled on the TV show Grand Designs.

Profit from a consumer boom

As we know from our own property bubble in Britain, a buoyant housing market also means booming sales of furniture, materials and fittings. There are many practical reasons for this: new houses need bathrooms and kitchens. But the ‘wealth effect’ (where you feel wealthier because your house price has risen, even if your income hasn’t) also means rising house prices boost consumption.

Furniture sales in Germany are growing at a healthy rate of around 6% a year. Amazingly, despite the recession in the rest of Europe, furniture exports have grown too, at double-digit rates. Nearly a third of goods produced now end up abroad. To maintain this edge, many German firms focus on integrating technology into furniture. For instance, Alno has developed kitchens with remote-controlled tops, adjustable to the user’s height. Similarly, Gaggenau offers an integrated cooking system, controllable via a smartphone-style device.

Traditionally, Germans have had little enthusiasm for DIY. As consultancy McKinsey notes, two years ago, spending per head was only €467, far behind France on €602 and Britain on €709. Germans also tend to buy the cheapest tools, driving down profit margins. But this seems to be changing. Spending on equipment used in home improvements, especially power tools, is taking off. Analysts expect the overall market to grow by around 5% a year for the foreseeable future. Firms are also starting to pay attention to the potential of online sales and social media.

A few weeks ago Praktiker AG, which owned one of the major DIY chains, filed for bankruptcy, after it took on too much debt, and the sale of a subsidiary fell through. That may not sound promising, but it will reduce competition in the sector, helping profit margins increase for the remaining firms, at a time when demand for their goods is only set to grow. We look at how to profit from all these trends below.

Six of the best investments

Germany has seven stock exchanges (Berlin, Hamburg, Hanover, Munich, Stuttgart, Düsseldorf and Frankfurt). By far the most important is the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, which is where most of the tips listed below are drawn from. Going solely by volume of shares traded, it is the tenth-largest market in the world, with many large German companies listed on it.

If you want to buy one of these blue chips, there are several British brokers and spread-betting firms, such as Saxo Capital Markets, you can use. The exchange also lists several smaller companies, along with the secondary listings of many Asian firms. As many of these companies are relatively illiquid, you may need to shop around to find a specialist broker willing to deal in these.

Bien-Zenker (FRA: BIE) is one of the main manufacturers of prefabricated houses, a sector that is growing strongly. It also provides a range of services to the wider German construction industry. These include financial advice, architecture and design, and management of building sites. Its shares have surged in the past year, nearly doubling in value, while sales have risen by nearly a third over the last two years. The stock trades on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 16, and offers an attractive yield of 3.5%.

Another company that should do well out of the German housing boom is Creaton AG (FRA: CRN3). Creaton makes and distributes clay roof tiles for the construction industry. The tiles are produced in a wide range of styles and materials, including flexible tiles and special shapes. It also makes other roofing-related products and various types of cladding. Although its main subsidiary is in Germany, it also has substantial sales in Central Europe. It trades on a p/e ratio of 9.6, with a dividend yield of 2.35%.

If Germans continue to spend more on DIY, Hornbach Holding AG (FRA: HBH3) should be in a prime position to benefit. It owns a 75% stake in the third-largest home improvement and garden centre chain in Germany. It also owns a subsidiary that sells to the trade via a builders’ merchants chain. While profits have been hit by recent cold weather, sales have been growing by double digits since its foundation in 1987. It trades on a forward p/e of 11.7.

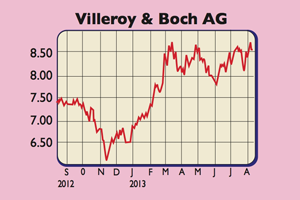

Villeroy & Boch AG (FRA: VIB3) makes tableware and ceramic fittings for kitchens and bathrooms. While Germany is its largest market, it also enjoys strong sales growth in Britain and Russia. A joint venture with Indian firm Genesis Luxury Fashion should also boost revenues on the subcontinent. While it currently trades on a p/e of 14.8, this is set to fall to 11.3 in 2014. It yields 3.6%.

While most of the ways to buy into the German property boom involve buying German shares, the Taliesin Property Fund (Aim: TPF) is one of the few pure plays listed on the London markets. Taliesin is a property investment company that aims to make money by buying property (both residential and commercial) in Berlin and eastern Germany. While this is riskier than buying in more prosperous parts of Germany, there are higher yields on offer, along with more chances of capital gains. The firm trades on eight times earnings, and does not pay a dividend as yet.

TAG Immobilien (FRA: TEG) is another promising-looking property fund. It holds a broader range of properties than Taliesin, but remains focused on finding value. Rental income has grown sharply from €46m in 2009 to an estimated €254m by 2013. However, the fund remains relatively conservatively financed with an average loan-to-value of 57%. It trades at book value and is profitable enough to pay a dividend of 3.4%, while still having ambitious plans for expansion. The average occupancy rate of its residential properties is 90.6%.