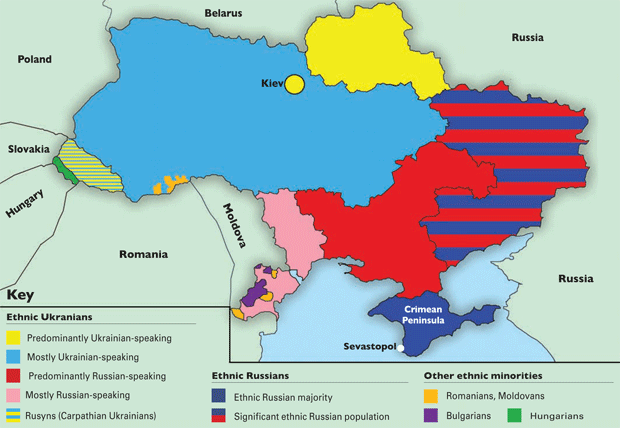

The Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea (see map below) lies at the heart of a region that has always been hugely strategic, notes Liam Halligan in The Daily Telegraph. With Russia tightening its grip on Crimea following the toppling of Ukraine’s pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, the “economic and political stakes” remain “sky-high”.

The West fears a “resurgent” Russia and there are anxieties about western European energy security and the “systemic fall-out if a near-bankrupt Ukraine defaults on its sovereign debt”.

Russia supplies more than a third of western Europe’s gas and many powerful Western firms are heavily committed in Russia. This will “seriously complicate” any attempt at economic sanctions.

In short, “Moscow has its thumb on our economic throat”. It also has fiscal strength on its side. Government debt is the lowest of any major economy. Moscow has currency reserves of $450bn, so it “holds most of the cards” when it comes to rescuing Ukraine financially at a time when “little Western cash has emerged”. When it comes to “statecraft and diplomacy, money talks”.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t act, says the Financial Times. EU leaders must draft a “series of escalating measures against Moscow” including sanctions, even if they could undermine our business interests.

They may be a “blunt tool”, but “sceptics need only look at their success in bringing Iran back to the negotiating table to be reminded of their usefulness”. As Putin “ponders his next move he must know that he faces a strong and united EU”.

This is vital, agrees Malcolm Rifkind in The Guardian. If Western reaction is limited to “rhetorical protest and a few symbolic gestures like the boycott of the G8 meeting”, this will embolden Putin. Eventually we will see “aggressive action against the Baltic states, further denial of Georgia’s territorial integrity, and pressure to separate eastern Ukraine from the rest of that country”.

Putin is not Hitler. But the fact remains that “the last time the alleged need to protect ethnic brethren was used as a justification for invasion and annexation in Europe was the Sudetenland, and the shame of the Munich Agreement in 1938”. Since he came to power, Putin’s aim has been to reassert control over Russia’s “near abroad”.

It would help if Arseniy Yatsenyuk, interim prime minister of Ukraine, gave Moscow an explicit, public reassurance that Russia’s lease on the Sevastopol naval base will be honoured and that it will chart an orderly course to the “greater autonomy that will almost certainly have to follow a Crimean referendum”, says The Times.

The Kremlin propaganda machine is milking the idea that Russians are at risk. Even as he appeared ready to ‘de-escalate’, Putin spoke of Russia being involved in a “humanitarian” mission on behalf of Russians at risk of “annihilation and torture”.

This is “patent nonsense”, but it is “nonsense that may be blinding Putin to the fundamental rule that military intervention in another country must have consequences”.