Investors who have risked their hands and been bitten might be wary of Russia. But every market has its price, says James McKeigue.

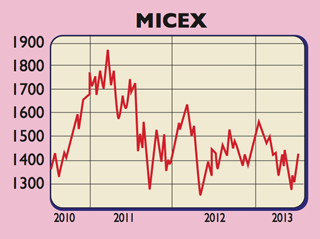

For long-term investors in Russia’s stockmarket, the country’s national symbol of a bear feels depressingly appropriate. Russia’s main market, the MICEX, is down 20% over the last two years, while annual GDP growth slowed to an annualised rate of 1.6% in the first quarter. That might not be as bad as Britain, but it’s a big drop from the 5.3% average annual growth Russia enjoyed between 2000 and 2012. Given that this promise of fast economic growth is what tempted foreign investors to brave the endemic corruption and poor corporate governance in the first place, it’s little surprise that many have run for the exits.

We can understand why many investors are cutting their losses. Russia faces several long-term challenges that will continue to hamper its growth. But the fact is that every market has its price – and Russian stocks are now so cheap that they look as though they have priced in all but the most apocalyptic scenarios. Russian stocks now trade at a big discount to both their historic average and to their emerging-market peers. So it looks like a good time to go shopping and pick up some Russian bargains.

But first, let’s get Russia’s problems out of the way so that we know we’re investing in the country with our eyes wide open. The most obvious question is: why is the economy slowing? One reason, says William Jackson from Capital Economics, is that much of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. “The dismantling of the Soviet economy, the ensuing recession and the subsequent rise in unemployment left Russia with a huge amount of under-utilised labour and capital.” The existence of all this ‘spare capacity’ meant that, when demand recovered, firms could increase output without upping investment or causing inflation to rise. Now that spare capacity is pretty much gone. That’s one reason why prices are rising – inflation is at 6.9% – despite weak economic growth.

One obvious solution is for Russia to invest in new productive capacity. Unfortunately, that doesn’t look like happening any time soon. It’s not that the country hasn’t got the money – it has one of the highest saving rates among emerging markets. The problem is that Russians are wary of reinvesting in the local market. A poorly developed financial system and poor corporate governance means rich individuals and businesses prefer to stick money in saving accounts, or invest it abroad, than put it to work in the local economy. As a result Russia has high net capital outflows – around $80bn last year – a sharp contrast to other emerging markets, such as India or Brazil, which receive heavy inflows.

This poor business and investment environment has its roots in Soviet times. Back then, a centralised planning system created powerful officials at every level of society, which encouraged people to bend the rules to get ahead. When that system was taken apart at breakneck speed during the chaotic Boris Yeltsin years, rising oligarchs created giant corporations that grew far more powerful than the nascent institutions set up to govern them. Meanwhile, the arrival of ex-KGB strongman Vladimir Putin as president in 1999 created a government that isn’t afraid to intervene directly in business deals.

The result is that foreign investors buying into Russian companies today will often be the least of the firm’s priorities. Accounting scandals, fraud, dodgy court decisions or plain old government expropriation have all hit investors’ pockets in recent years.

“Russian stocks have all but the most dire scenarios priced in”

Another worrying sign is that the commodity export boom that has powered Russia’s economy since the 2000s is starting to falter. Put simply, Russia’s exports are made up of sales of metals and energy to Europe and China. When commodity prices were booming, that model brought in a steady stream of foreign cash that buoyed consumers and helped the government fix its fiscal situation. But now metal prices are down, while Europe and China’s economies are struggling. So far energy prices have held up, but the spread of unconventional energy – using new techniques to tap once-inaccessible oil and gas reserves – could threaten those too.

There are already signs of this affecting Russia. Gazprom, the state-run giant that until recently had a monopoly on gas exports, has been forced to discount deals for European partners. As more countries develop shale deposits for export, and others develop the facilities needed to import seabourne supplies, Russia’s piped gas supplies will face more competition. Given that energy companies account for half the value of Russia’s stockmarket, this is likely to hit investors. Gazprom has already taken a battering, with its share price down almost 80% since mid-2008.

In light of the above, it’s understandable that some investors are nervous. Yet, while many worries are well-founded, much of the bad news is already in the price. Russia’s travails have left the MICEX on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 6.3, far cheaper than emerging or developed market peers. Russia also looks cheap when measured by its cyclically adjusted p/e (CAPE) ratio. This works like a p/e ratio, but divides the price by the average of ten years’ earnings to smooth out any anomalies due to fluctuations in the business cycle. On a CAPE of just 6.2, Russia is one of the world’s cheapest markets.

It is cheaper than insolvent, recession-hit economies such as Spain and Italy, which are hardly strangers to corruption themselves. It is far cheaper than all of its fellow Brics – the fashionable emerging market club made up of Brazil, Russia, India and China – and less than a third of the price of its old enemy America. Of course, sometimes things are cheap for a reason. Yet with the market currently ranking Russia alongside bankrupt countries such as Greece, it would seem there has been an overreaction.

Moreover, Russia’s situation is not as bad as it seems. Take energy. Shale may hit Russia in the short and medium term, but it’s worth remembering that, as well as its supplies of conventional energy, Russia is estimated to have the world’s largest supply of shale oil and ninth-biggest supplies of shale gas. With global energy demand expected to rocket – the International Energy Agency expects an increase of 30% by 2035 – Russia looks well-placed to benefit. It has already taken steps to boost production. Gazprom’s monopoly on gas exports was broken for the first time recently when Novatek, an independent gas producer, was permitted to make a joint venture with China National Petroleum Corporation in a planned $20bn liquefied natural gas (LNG) export plant. At a recent conference, Putin indicated that this was the first step in Russia liberalising its LNG export sector.

As for the economy, there are a number of reasons to think the situation will improve. One is that while economists may bemoan the loss of ‘spare capacity’, for the people in the street it’s a good thing – unemployment at 5.6%, is among the lowest levels in Europe. And competition for labour means the average monthly wage, measured in euros, has increased by almost 80% since 2009, says François Chauchat from GK Research. This is reflected in a buoyant consumer market. “Vehicle sales in Russia are running at three million a year” – far bigger than in Britain. “Russia’s retail market is now bigger than those of France or Germany with annual sales of e550bn.”

Russian bank Sberbank goes further, claiming that despite Russia’s reputation as an energy-based economy, it is actually more reliant on consumer spending. It notes that while “the extractive industries of oil, gas, metals and mining, and utilities represent two-thirds of the Russian equity market…the remaining consumer-related sectors, which represent two-thirds of GDP, have driven more than 80% of domestic GDP growth since 2004”. One reason for the spending strength is that, compared to other Brics, Russia’s GDP is fairly equitably distributed. “Based on $15,000 annual median income, 55% of Russia’s households are in the middle class, versus 30% in Brazil, 21% in China and 11% in India.” Sberbank expects this consumer boom to continue, pencilling in 23% growth in retail sales in 2013. By 2020 it expects Russia’s consumer market to be the biggest in Europe and fourth-most valuable in the world.

“Putin is ready to tackle the economy’s big problems”

Of course, if Russia’s economy went into a deep recession all these predictions would go out the window. But – barring a global recession or energy price collapse – Putin has the will and the means to keep the consumer boom going. When he came to power in 1999 he signed an unwritten contract with the Russian people, says The Economist: in exchange for power, he guaranteed them increased wealth and security. He delivered this by channelling the proceeds of Russia’s energy wealth into pensions and healthcare. With Russia in a strong macroeconomic position (it runs a balanced budget, enjoys low public debt and a meaty sovereign wealth fund), there is little sign this will change.

Putin has indicated that Russia is also prepared to use some of this fiscal strength to boost growth. He plans to dip into its sovereign wealth fund, currently worth $187bn, to launch $14bn of transport projects.

We’ve heard this before, but Putin finally seems ready to tackle some of the economy’s biggest problems. Last year he championed Russia’s entry into the World Trade Organisation (WTO). For a man with a penchant for intervening directly in business deals, and under whom state firms have grown, it may seem a strange move. Signing up to the WTO subjects Russian firms to international rules. The move was the clearest sign yet that Putin, who has often stated that Russia’s business environment must improve, is prepared to make that happen.

Another important process is financial reform. “This is an ongoing, and slow, process but we are starting to see progress,” says Gordon Fraser, a fund manager at the BlackRock Emerging Markets specialist team. He points to the recent decision to merge Moscow’s two exchanges, create a central securities depositary and reduce settlement time for trades, as evidence that policymakers are serious about improving the investment environment. While Fraser admits there have been “many publically reported instances of negative developments”, he believes these reforms will attract new investors and raise standards. He also feels the state is becoming more aligned with minority shareholders than ever before. “There is a push for companies to increase their dividends, as this would benefit state revenues as it is also a major shareholder.” If widely touted dividend reform went through, it would boost what is already a generous dividend-paying market.

We’re not saying sink your pension fund into Russia. But if you have a portion of your portfolio to allocate to more risky investments, it looks a bargain right now. We look at some of the best bets below.

The five investments to buy now

Our favourite fund for playing Russia is BlackRock’s Emerging Europe investment trust (LSE: BEEP). It underperformed its benchmark in 2012, recently changed its focus, its name, and halved the number of holdings in the portfolio to around 25. “We believe you need a selective approach in markets like Russia to deliver the best returns”, says BlackRock’s Gordon Fraser. Given the poor performance of some Russian stocks, we’d agree.

If you’re paying for active management there’s no point buying something that acts like a tracker. Rarely for a Russia-focused fund, its main weighting is to financials. If more financial reforms go through, the sector should benefit. But the fund doesn’t ignore energy. Its second-largest holding is state gas producer Gazprom. This suffers from political interference but is unbelievably cheap. The fund is a big believer in the consumer theme, with stakes in supermarkets and mobile-phone outfits. It currently trades at a discount to net asset value (NAV) of almost 10% and is offering investors the chance to sell out for NAV, regardless of any discount, in five years’ time.

If you’d rather track the market passively, you could use an exchange-traded fund (ETF). There is a range of options, from the iShares MSCI Russia Capped ETF (LSE: RUSS), which tracks the market’s biggest 28 stocks and is weighted towards energy and materials, to specialised small cap trackers, such as the Market Vectors Russia Small-Cap ETF (NYSE: RSXJ).

If you want to buy Russian stocks directly, we like Sberbank (LSE: SBER). It is a solid retail bank with an extensive Russian presence. The bank has also grown its product range and is now the top provider of credit cards, with a 22% market share, and mortgages, with 47%. Despite worries in some quarters about a credit bubble – the central bank is bringing in rules to slow loan growth to more sustainable levels – there is plenty of room left for expansion. Russia’s ratio of household debt-to-GDP hovers around 11%, compared to 20% and 30% in peers Turkey and the Czech Republic respectively. With less than 20% of Russians owning a credit card, Sberbank should have plenty more scope for making sales. It is trying to become a more comprehensive financial outfit and break into investment banking, buying Troika Dialog, Russia’s oldest brokerage. The shares look good value on a forward p/e of just six.

Above, we outlined the attractions of the Russian consumer theme. Unfortunately, the most obvious plays, such as listed supermarkets, are very expensive. However, one indirect way into consumer spending is through mobile phones. The Russian industry is backward by international standards. The world’s largest country by landmass, it’s proved difficult to build the wireless infrastructure needed for good mobile data service coverage. Smartphone sales have been sluggish, making up just 10% of the market.

However, Russia’s four major wireless carriers have just agreed to spend $13bn on building the fourth-generation technology needed to speed up the network. As a result, network speeds should increase by 17 times between now and 2017, while smartphones numbers are expected to triple. That’s good news for Mobile TeleSystems (NYSE: MBT), Russia’s largest mobile phone operator, which has a smartphone-focused strategy. It was the first operator there to create tariffs that give unlimited voice minutes to data users in a bid to tempt smartphone owners. The firm also offers cheap, Chinese-made smartphones to persuade more of its customers to sign up to data packages. Already in a market-leading position, the firm aims to make more from each existing customer through data services rather than by growing market share. It looks cheap on a forward p/e of 7.5, especially when you consider its historical p/e is 13.