Cyprus broke all the rules this week. First, it stunned savers across the eurozone when it proposed that bank deposits – and those of small savers in particular – were fair game in order to secure a bail-out deal from the eurozone.

In Europe, savings of up to €100,000 in any bank are meant to be protected from loss. This deposit insurance exists for a very good reason: to prevent bank runs. The idea that savings over and above that level could be confiscated was controversial enough. Taking it from those with less than €100,000 in the bank broke a real taboo – even if you argue that it’s a tax, and therefore not within the remit of the deposit insurance scheme.

As Marcus Ashworth at Espirito Santo Investment Bank put it: “Depositor sanctity is such a fundamental concept as to be at the heart of any fiat money system – without trust that your money is safe within a bank… then we are back to groats and the barbarous relic as the only true stores of value.”

Then, having scared everyone and shut down the banks, the country did a U-turn, as the understandable outcry forced the Cypriot parliament to reject the deal comprehensively. But the damage was done.

It’s not clear when the banks will re-open, but the chances of any sensible saver keeping a substantial sum of money within the vaults when they do seem slim. And now that Cyprus has breached the taboo, savers in banks across the eurozone – and troubled nations like Spain, Portugal and Greece in particular – can’t be feeling terribly comfortable either.

But the biggest rule that Cyprus broke was this one: when you steal the ordinary citizens’ money, you’re not supposed to tell them about it. As far back as the 17th century, French politician Jean-Baptiste Colbert recognised that “the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest amount of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing”.

And this is where the Cypriot government went wrong; because while we British might like to imagine that what happened in Cyprus couldn’t happen here, it already has.

How British savers are losing out

Let’s say that you – a British saver – had put £50,000 of savings in a bank account in Cyprus at the start of 2008. At the going exchange rate back then (around 74p to the euro), you’d have received around €67,600. Over the last few years, Cypriot bank accounts have paid a typical rate of around 4%-5% a year on deposits, according to Credit Suisse. So by now, you’d have €84,240 (assuming a 4.5% a year average interest rate).

Let’s knock off 6.75% for the bank levy (which looks unlikely to happen now, in any case). That gives us €78,554. Convert that back to sterling at the current exchange rate of around 85p to a euro, and you’re left with £66,770.

Compare that to keeping £50,000 in a UK bank account since the start of 2008. At an average interest rate of 3.12% (a figure boosted by the fact that savings rates were still quite high in 2008), you’d now have just £58,317. In other words, even given the banking levy, you’d have been £8,453 richer now by banking in Cyprus.

Let’s throw in the impact of inflation. Since 2008, the UK retail prices index has risen by 17.2%. So for your £50,000 to retain its purchasing power, it would have to have grown to £58,579 by now. So only the Cypriot option would have delivered you a ‘real’ (post-inflation) return. By saving in Britain, you’ve actually lost £262-worth of purchasing power.

Indeed, as Ian Cowie pointed out in a blog for The Daily Telegraph this week: “Millions of savers have already lost much more of the real value or purchasing power of their money to prop up financial institutions closer to home.”

Now, we’re not recommending for a moment that you bank in Cyprus. The banks in Cyprus remain shut at the time of writing, and the threat of capital controls – whereby transfers of money are capped and monitored – is being bandied about. So the chances are that any hypothetical person who had opted for the Cyprus option would now be wishing they’d stuck with keeping their savings in Britain.

In short, Cypriot deposit rates were high for a reason – savers were being compensated for the risk they were taking by keeping their money within an obviously insolvent banking system, even if many of the smaller savers didn’t fully understand that.

However, it’s a very clear demonstration of how the collapse in the pound since 2008 has stealthily acted to make British savers far poorer over the past few years.

The great wealth repression scheme

So why is this happening? It’s all part of the ‘financial repression’ playbook. As we all know, Britain is heavily indebted. We have one of the highest deficits in the world (in other words, for all the talk of ‘austerity’, the government spends a lot more than it collects in taxes each year). That means our national debt keeps rising too.

Even if you exclude all the ‘off-balance-sheet’ debts, such as bank bail-out costs (which are extensive), our debt-to-GDP ratio is around 74%. And this is only rising – Chancellor George Osborne had to admit in the Budget this week that he has missed his ‘deficit reduction’ targets. We’ll still be spending more than the tax take by 2017. Meanwhile, our financial sector and our consumers are also heavily indebted.

All of this debt is holding back the country’s growth, and leaves us very vulnerable to any future increase in interest rates. As Kathleen Brooks of Forex.com notes: “Interest rates are low until they are not and then economic disaster becomes a real possibility. Just ask Spain and Italy, or Greece and Portugal. The consequences of being reliant on living on debt when interest rates are volatile and rising is not the place you want to be.”

So how do you get rid of it? As we’ve noted before, there are three main paths. The pleasant way is via growth: you become more competitive through efficiency gains rather than pay cuts, you grow your economy, everyone makes more money (including the government), and the debt gets paid off that way.

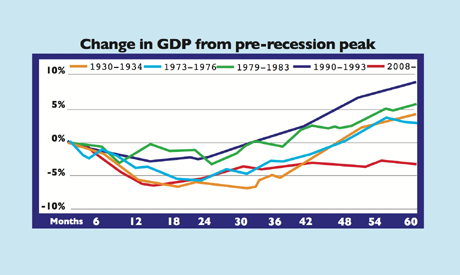

Unfortunately, growth in Britain is conspicuous by its absence. This has been one of the slowest ‘recoveries’ on record (see the chart below). And the government is too timid and internally conflicted to push through any significant reform measures that might improve Britain’s prospects. So growth is unlikely to be our escape route.

Source: National Institute of Economic and Social Research / The Guardian

The second option is explicitly to default. Everyone takes a pay cut. Debts get written off, asset prices fall, and lenders lose their money. This is the route that the eurozone is trying to wobble its way down. As Cyprus shows, they’re not proving very successful.

At the first sign of default, lenders panic and try to call in their loans before you can default on them. It can work if you do it hard and fast enough. But it’s not an option for the UK – if Britain was to default on its debt outright, it would make the crash of 2008 look like a minor economic squall.

That leaves the third option. You repay your debts, but you do it with devalued money. It’s just like defaulting, but nowhere near as ugly. By having the Bank of England buy gilts (UK government debt) through quantitative easing (QE), the government gets to borrow at interest rates that are below inflation. So in effect, it can borrow £100 today, and repay the debt with £99 tomorrow.

Low interest rates also act to prop up house prices, which in turn helps to keep the banking sector solvent. Meanwhile, pay rises for workers are failing to keep up with inflation, which, combined with the devaluation in sterling, makes the labour force more competitive without forcing through pay cuts.

It sounds like the perfect solution. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch. So who pays? With inflation above interest rates, savings lose value in ‘real’ terms, while efforts to keep the government’s borrowing costs down also mean that annuities – the income stream that most people still have to buy with their pension funds when they eventually retire – are at their lowest levels in years.

In 2008, a £100,000 pension pot could buy a 65-year-old man a level income of £7,850 a year. Now it’ll only buy him around £5,900 a year. As The Economist puts it: “Savers will pay for the mess. They are the only ones that have any money left.”

In short, you can and should expect the government and the Bank of England to continue to pursue inflationary policies – indeed, Osborne gave the Bank a clear signal to maintain loose monetary policy at the Budget, by enshrining its right to “look through” above-target inflation levels as long as the economic backdrop justifies doing so.

That’s not all. ‘Fiscal drag’, whereby tax allowance levels are left frozen, or rise at an even slower rate than wages, will drag increasing numbers of people into higher and higher tax bands, or into the clutches of taxes such as inheritance tax and capital gains tax. Beyond that, there’s the prospect of entirely new taxes.

As Dr Tim Morgan of Tullett Prebon notes: “Beyond such stealthy transfers, could expropriation become both more blatant and even more rapacious, with, for example, the introduction of a ‘wealth tax’? The government knows that it must do anything – literally anything – to stop rates from rising. Only the bravest would bet that the definition of ‘anything’ would stop short of further asset transfers from prudent individuals to a spendthrift state.”

So what can you do about this?

How to protect your wealth

Before we say anything else, it’s important to clarify one point: if there’s a lesson from Cyprus, it’s that nothing is safe. A determined and desperate government can tax or target whatever it likes, and short of actively breaking the law (which we certainly don’t recommend), there’s nothing you can do about it.

However, you can take precautions by trying to avoid the most obvious targets. For a start, we’ve been regularly urging you to diversify out of sterling since the start of this year. So far that’s been a good move, with the pound falling from around $1.63 to around $1.51 now.

It looks as though the pound’s losing streak may well continue – Sir Mervyn King has tried to arrest the decline in the past week by talking up the pound, and the panic over Cyprus has distracted attention from Britain. But Britain’s fundamentals are poor, and a weaker currency is seen as part of the solution by the authorities, so don’t expect the bounce to last.

Where should you diversify into? We’re happy to own assets denominated in falling currencies – such as cheap Japanese and European stocks, which we regularly write about – because we expect the gains in the stock markets to outweigh any losses on the currency side (particularly given how fragile sterling is). However, if you’re looking for a strong currency to diversify into, we think the US dollar is the one to back.

Although the Federal Reserve is still desperately trying to devalue the dollar, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for the US to win the global currency war. While its economy remains weak, the data are still more impressive than for most other developed economies.

With all the excitement over America’s access to cheap natural gas, and the rallying property market, the US simply looks like one of the least ugly options.

On top of that, as Russell Napier notes, the US is seen as a more capitalist-friendly nation, and therefore a safer bet, certainly than Europe. “While this might not be the case in the long term, the relative protection of private wealth in the US, following the sequestration of euro bank deposits by the dictat of an unelected regime in Brussels, is without question.”

There’s another ‘currency’ you should be looking at – gold. So far in 2013, the yellow metal has had a pretty poor year. In US dollars, the price has fallen from $1,685 to $1,605. This has given much cheer to the gold permabears. Why on earth, amid all the panic, they ask, is gold so lacklustre? The answer is pretty straightforward – it’s down to the strengthening US dollar.

The best way to think about gold is as another currency. Depending on sentiment, it will go up and down against all the other currencies in the world.

This year so far, for example, it’s up by 6% against the Japanese yen. More importantly, for sterling investors, it’s up by 3% against the weak pound.

What makes gold different – and this is what gives gold its function as portfolio insurance – is that it doesn’t derive its value from the government, and it doesn’t require a fully functional financial system to be a viable means of exchange. That means it’s always worth holding some, in case of emergencies.

You should put 10% of your portfolio in it, and then hope it doesn’t go up in value (because if it does, that usually means that there’s something amiss in the financial system, and the rest of your portfolio will be hurting).

As for fears over gold confiscation, it’s worth remembering that the most significant episode of confiscation (in the US in 1933, under the then president Franklin D Roosevelt) occurred when much of the world was still on the gold standard.

Confiscating gold today would endow the metal with a level of importance that monetary authorities (in the West at least) would be loath to grant it. So while it can’t be ruled out (nothing can), things would have to get a lot worse than they are just now.

Finally, make use of your tax-free allowances. It’s hard enough to make a ‘real’ return without having to worry about the impact of income and capital gains taxes on your money as well.

There are two main tax-advantaged ways of saving in Britain: via an individual savings account (Isa), and via a pension. If your company offers a pension scheme, to which it contributes, then it’s usually worth signing up for – the contributions made by the company make up for any disadvantages.

But if you are investing for yourself, we would make use of your Isa allowance before you decide to open a self-invested personal pension (Sipp).

Why? Because pensions are a honey pot for cash-strapped governments. And there’s a good reason for that. If we asked you how much money you had in your Isa account just now, to the nearest £5,000 say, you’d probably be able to give a pretty accurate answer off the top of your head. Even if you couldn’t, you’d probably only need to check one piece of paper, or one website, to find the answer.

What if we asked the same question about your pension fund? I suspect this might be easier for MoneyWeek readers to answer on the spot than for most, but even so, I imagine many would struggle. And getting an accurate valuation would involve flicking through a lot more paperwork.

That’s why pensions are attractive to governments. There’s a mound of cash just sitting there. And in the main, the rightful owners of this cash – us – don’t have any real idea of what it’s worth, or how much should be in the pot at any one time.

In fact, most of us prefer not even to think about it because we have such a bleak view of what it will take for us to retire.

So compared to targeting Isas or cash in the bank, pensions are a doddle. Clearly, if you have enough money to fill up your annual Isa allowance with some left over to spare, it makes sense to have a Sipp. But if not, we’d prioritise the Isa – just make sure you have the will power to avoid pillaging the fund before your retirement date.