America’s Dow Jones index is only 4%-5% below its all-time high of 14,164. It reached this milestone five years ago, just before the credit crunch kicked in. Excited talk of a new record, however, only serves to highlight how little progress American stocks have made since the turn of the century.

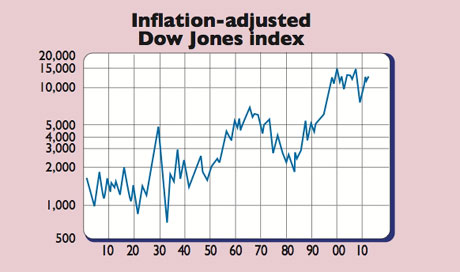

America’s S&P 500, deemed a fairer reflection of the US market as it covers 500 firms, compared to the Dow’s 30, is at levels first seen in 1999. In real terms, stocks have fallen. The inflation-adjusted Dow is 15% below its 1999 high (see chart).

The indices’ poor performance since the tech bubble burst is a reminder that, for more than a century, US stocks have moved in long, multi-year (or secular) cycles. Secular bull markets show a rising trend and secular bear markets a flat or downward one.

Since 2000, stocks have been in a secular bear market. That followed the record 1982-2000 bull run, which followed the bear market of the late 1960s and 1970s. The economic backdrop affects secular trends. 1982-2000 was an era of deregulation and privatisation; in the 1960s and 1970s, high inflation crimped growth and equity returns.

Since 2000 America has been grappling with burst bubbles and deleveraging. It tempered the impact of the burst tech bubble by blowing up a worse debt and housing bubble, which burst in the crunch five years ago.

Another key feature of secular markets has been the journey from very high valuations to very low ones and back again. Valuations revert to the average after falling below it and going above it.

At the market peak in 2000, the cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio, or Shiller p/e, hit a record 45. In 1982 at the start of the bull run it had fallen into single digits. A low Shiller p/e, then, has been a reliable predictor of good long-term returns.

At present, the Shiller p/e is still historically high at 21, a far cry from the single-digit levels that imply good long-term returns. But the good news is that Shiller p/es in Europe are at the low levels that presage healthy returns.

The upshot is that Western indices may not shake off the credit-crunch hangover soon. However, in Europe, unlike in America, they are already cheap enough to be a solid bet for patient investors.