We learned a new word this week: ‘goldenfreude’. It’s a word coined by Joe Weisenthal of the Business Insider website to describe the sense of sheer glee felt by many financial pundits at this week’s plunge in the gold price.

On Friday, the gold price started the day at around $1,560 per ounce. By the end of the day on Monday, the price had fallen well below $1,400, dropping as far as $1,322 at one point. Resounding cries of “gold is dead” and “Bernanke has won” spread across Twitter and the blogosphere.

It’s understandable that anyone who has stood on the sidelines and watched gold’s remarkably steady rise over the last decade or so might feel a little touchy by now. But this extraordinarily visceral reaction is a testament to the hold that gold still has on the emotions and imaginations of bulls and bears alike.

The shiny yellow metal carries more political and moral baggage than any other asset class we can think of – and that includes UK residential property.

At one extreme, ‘goldbugs’ see gold as the one true currency. The ills of the modern world – from global warfare to soaring living costs – are largely due to the abandonment of the gold standard. When the price of gold falls, it’s because governments and their lapdogs, the big investment banks (or is it the other way round?), are deliberately manipulating the price in order to hide the true state of things.

At the other extreme, those who hate gold view it as a primitive leftover of no value whatsoever. Modern monetary systems, run by central bankers who know exactly what they’re doing, have no need of it. Holding gold is a positively anti-social action that demonstrates an unseemly lack of faith in progress.

At MoneyWeek, we’re more concerned about what role gold plays in your portfolio than in the politics of it all. But we’d argue that the goldbugs at least have history on their side. Central bankers have presided over bubble after bubble in the asset markets. To assume that they’ve now got their act together and know exactly what they’re doing is to put a great deal of faith in a group of people who have yet to prove worthy of our trust.

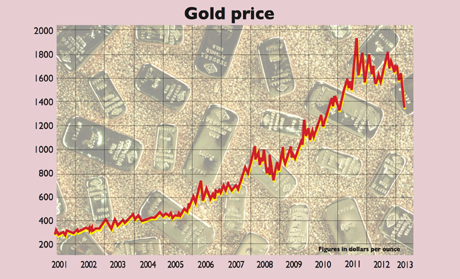

Having said that, we’ve also been pointing out for a while that gold is no longer cheap. At the start of this century, when you could still buy an ounce of gold for less than $300, it was clearly good value (even if few people recognised it at the time). The price was low by historic standards, and putting a significant proportion of your net wealth into gold back then made sense purely from a value investing point of view.

That’s no longer the case. Gold is very difficult to value – it pays no income, which is the basis of any serious measure of fundamental value – so anyone attempting to value it has to find more esoteric measures. But even where it is now, at $1,350-$1,400 an ounce, it isn’t the spectacular bargain it once was. So, as we’ve said with growing regularity over the past 18 months or so, you should view it as portfolio insurance. Hold 5%-10% of your wealth in gold, and hope that it doesn’t go up.

Why the crash?

We’ll return to this view of gold as insurance in a moment. But firstly, why the crash? There are lots of theories being knocked around about what drove it. It was certainly unprecedented. Using the financial industry’s (admittedly, horribly flawed) standard measures of risk, the sort of move we saw in gold on Friday alone should only happen roughly once every 5,000 years.

Clearly, that’s nonsense – it happened, after all, just as the 2008 stockmarket crash did, which was also supposed to be a statistical near-impossibility – but it gives you an idea of just how dramatic the slump was.

Yet it’s proved very difficult to pinpoint one explicit reason for the crash. One theory blames Japan’s promised money-printing spree. The Bank of Japan’s determination to ramp up inflation, while buying huge wads of government bonds at the same time, has sent the Japanese government bond (JGB) market haywire.

With prices bouncing around far more than usual, the argument goes that traders and banks in the sector have had to put more money aside in order to hang on to their positions. As a result, they’ve sold out of gold and other liquid positions to raise cash.

Others (including Goldman Sachs) say the trigger event was Cyprus potentially being forced to sell its gold. Now, Cyprus’s gold reserves are tiny by comparison to global supply. But if Cyprus has to auction off its gold, the bearish thinking goes, then maybe Greece will be next, or Portugal, or even Italy.

An alternative argument is simply that gold’s bull market is long in the tooth, and finally gave way to boredom. As far as James Ferguson (one of the few regular MoneyWeek contributors who is actively bearish on gold) of Macro Strategy Partners is concerned, gold’s price action since it peaked in 2011 has been that of a “classic, tired chart, with more and more people getting more and more worried about opportunity cost”. When gold slid through important ‘technical’ levels, “everyone with a chart bailed”, and gold just couldn’t hold it together.

Of all the arguments, this last may be the one that gets closest to the truth. And it also fits in with the idea that gold is there as insurance against financial disaster.

The death of a bull market

Let’s think back to what killed the last gold bull market. In 1971, when President Richard Nixon severed the last link between the US dollar and gold, gold was worth $35 an ounce. It started to take off seriously in the mid-1970s and then, in 1979 alone, gold almost doubled in value, from just under $240 an ounce to just over $440. In January 1980, it spiked to $850 an ounce, a record high that would hold for more than 20 years.

At the time the annual inflation rate was in double-digit territory. Paul Volcker, then-Federal Reserve chairman, crushed inflation out of the economy by raising interest rates to a 1981 peak of 20%. In doing so, he also ended gold’s bull run.

The fact that gold’s bull run is so closely tied to the inflationary days of the late 1970s is one reason why it’s often seen primarily as a hedge against inflation. But it’s not that simple. We’d argue that what gold really hedges against is a drop in faith in the financial system, and central banks in particular. Gold didn’t drop because inflation was falling – it dropped because Volcker was taking charge of the financial system, and investors had faith in his ability to do the job.

And right now, strange as it may seem, faith in central bankers is making a comeback. At the heart of all this is a growing conviction that quantitative easing (QE) works. Investors have been watching the Federal Reserve (and the Bank of England) in their money-printing efforts since 2009.

QE hasn’t caused hyperinflation yet, and in America (although sadly not Britain) it hasn’t even contributed to much ordinary inflation. So there are no obvious signs of pending disaster on that front. Meanwhile, one thing is for sure – QE has driven up stock prices.

QE as cure-all?

So investors are increasingly willing to give central bankers the benefit of the doubt on this score. You can see this in action by looking at gold’s most recent price peak. That came in September 2011, when the eurozone was enduring yet another crisis.

By that point, investors had lost all confidence in the then-governor of the European Central Bank (ECB), Jean-Claude Trichet. But the next month, Mario Draghi took over as ECB head. Since then, he has won the confidence of the markets by promising to “do what it takes” to save the euro.

Investors have gone from viewing QE as a destabilising influence on the financial system to being a sort of cure-all. After all, America is already starting to talk about withdrawing QE. None of the feared ill-effects have happened yet. Perhaps they never will. And in the meantime, look at the benefits. Banks gone bust? Don’t worry, the central bank will stand behind them and bail them out. Better still, investors also now see QE as a cast-iron guarantee that share prices will go up.

So it’s little wonder that the Bank of Japan’s printing spree has turned out to be the final straw for gold. Why would you hold on to gold, which has been such a dull performer for the last couple of years, when the Japanese central bank is almost literally telling you what the Nikkei 225 will be worth in six months’ time?

In short, the last gold bull market died because investors had confidence in a central banker who promised to squeeze inflation out of the system and acted to back up his words. As a result, gold was no longer needed as an insurance policy against financial collapse.

Now the current gold bull market is faltering because almost the exact opposite is happening – the market is putting its faith in the ability of central bankers to kickstart the global economy again, without completely destroying the system. Again, the insurance policy no longer seems as attractive as it did maybe 18 months ago.

But does all of this mean that you no longer need the insurance? Of course not. Investors get bored easily. It’s particularly hard to sit on a poorly performing position when everyone around you seems to be making amazing gains by chasing QE-fuelled asset classes. However, it seems a huge leap of faith to us to then imagine that central banks have this completely under control.

The new role of central banks

Hiking interest rates to crush inflation out of an economy, as Volcker did, is one thing. It’s very painful in the short term. But the mechanism by which it works is pretty clear and well understood. QE, on the other hand, is a whole different ball game. Volcker himself doesn’t seem too optimistic about central banks’ abilities to juggle all the targets they have been given.

“The basic function of a central bank is to defend the value of the currency,” he told Financial Times writer Gillian Tett recently. Instead, central banks have been given the almost impossible task of trying to encourage inflation and growth, while all the time keeping borrowing costs for their heavily indebted governments as low as possible. The chaos in the JGB market mentioned earlier is just one example of how difficult this juggling act is to manage.

And what happens when it’s time for these policies to be wound up? “The challenge you face in running a low-interest-rate policy is when to end it. Inevitably you will end low interest rates too soon or not soon enough… The easy part is easing; the hard part is tightening.”

It’s going to be much tougher this time round than it was even in Volcker’s day. The Bank of England now holds around a third of outstanding UK government debt. The Federal Reserve holds about 10% of outstanding US government debt. The Japanese central bank is going to end up with vast amounts of JGBs. And the ECB is already on the hook for a lot of bad debt – it’s just not as transparent as the other three.

Another Bretton Woods?

How will these holdings of debt be returned to the market without government borrowing costs exploding? Or what happens to inflation when investors realise they never will be returned to the market? It’s not too far-fetched to imagine that we might one day in the not-too-distant future need to see another version of Bretton Woods to manage the restructuring of the global financial system to account for the state of developed world economies.

And even if it doesn’t go that far, there is a huge amount of scope for panics and mis-steps and – yes – disasters on the road between here and a more ‘normal’ financial system.

So in short, we’d hang on to your gold. We’re more than happy to have money in the stock markets – it’s worth taking advantage of all this QE, after all – and Japan in particular is one of our favourite markets right now. But you still need to hang on to that insurance. Keep 5%-10% of your wealth in gold, and hope that it doesn’t go up. Because when gold is going up, it tends to be bad news for most other investments.

Is it time to buy the miners?

Until last week, the decline of the gold price had been a relatively leisurely and gentle affair. But gold mining stocks have had a far more torrid time. The NYSE Arca Gold BUGS, or HUI, index, a US index of gold miners who don’t hedge their output, has fallen by more than 50% since its mid-2011 peak, compared to around 25% for the gold price.

Rising costs and a tendency for production levels to disappoint have been just two of the problems afflicting gold miners. Combined with the general fear around commodities in general, as China’s economy slows, it’s little wonder that the mining stocks have fallen harder than the gold price itself.

Now, unlike gold, we don’t see gold miners as portfolio ‘insurance’. Ultimately, gold miners are equities with all the potential individual business problems that companies might face. So if it’s insurance you’re after, just buy gold.

My colleague Paul Amery looks at some of the easiest ways to get exposure via exchange-traded funds here; or if you prefer to buy physical gold, you can go to a bullion dealer, such as ATS, or you can buy coins and have them stored for you by a company such as LinGold or BullionVault.

However, if you have an appetite for risk, the gold miners are starting to look interesting down at these levels. If you divide the level of the HUI index by the price of gold, you get the HUI/gold ratio. It’s currently at levels we haven’t seen since 2001 – and that includes the aftermath of the financial crash in 2008.

As you can see in the chart on the above, that’s very low by historic standards. As Eoin Treacy of Fullermoney points out, “there is no confirmation yet that they have reached a floor, but the sector is deeply oversold”.

One way to get exposure to a wide range of gold mining stocks is via the BlackRock Gold & General fund. This popular fund has had a woeful 18 months, as you might imagine, but if gold mining stocks turn a corner, it will be one of the beneficiaries. You should be able to buy the fund via your broker.