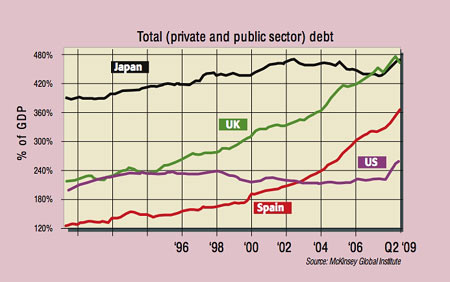

The bursting of the credit bubble has left a massive debt burden “that now weighs on the prospects for recovery”, says a new study by the McKinsey Global Institute. So a key question for developed world economies is how long and painful the process of cutting back on credit, or deleveraging, will be. Debt hit unprecedented levels in the years before the crisis. Britain’s private and public debt, for instance, jointly reached 469% of GDP in 2008. Only Japan has more overall debt.

The financial sector and households have at least made a start. Capital Economics notes that British households’ debt-to-income ratio has eased from 174% to 155%, although this is still sharply up from 105% a decade ago. McKinsey also notes that global financial sector leverage was actually back to the pre-crisis, 15-year average in mid-2009. But there is a long way to go. Overall debt levels in most big economies have barely budged as rocketing government debt has offset deleveraging elsewhere.

The McKinsey study examined 45 episodes of deleveraging since the Great Depression, 32 of which followed a financial crisis. In some cases, debt was reduced by a default, high inflation (which erodes the real value of the debt), or strong growth. But in half the cases, prolonged austerity, with credit growing more slowly than output, was the key.

In this scenario, the average country spent six to seven years deleveraging, with the debt-to-GDP ratio falling by around 25%. Deleveraging started two years after the crisis and growth shrank for the first two to three years before climbing above zero. The sectors that look especially overstretched and most likely to delever include households and commercial real estate in Spain, Britain and America.

With a growth boost via exports unlikely, given the simultaneous downturn in the West, McKinsey reckons that this time austerity is the most likely path to deleveraging, says Gillian Tett in the FT. But will Western voters “accept austerity without a backlash”? Don’t write off the chances of defaults or inflation. Yet if these appear too likely, government bond investors would probably “revolt and expedite the whole shebang” by demanding higher long-term interest rates, says Lex in the FT. Whether deleveraging happens quickly or slowly, however, it won’t be pleasant.