Is inflation or deflation the greater danger over the next few years? Will inflation take off now that central banks have cranked up the printing presses? Or, as the deflationists expect, will the credit squeeze bear down on growth and prices for years to come?

The most common argument against inflation flaring up is the so-called output gap, says Morgan Stanley. The “Great Recession” has created a gulf between actual and potential GDP, and all this spare capacity will take years to absorb. For example, the US Congressional Budget Office estimated that the output gap in the US was -6.2% of GDP in the first quarter. This implies that GDP could grow solidly for years before demand exceeds supply in the economy and it begins to overheat.

But estimating the current output gap is hardly an exact science, says Edward Chancellor in the FT. Economists can’t agree on how to measure it, for one thing, and estimates of potential growth can be wrong. Take the 1970s. The Federal Reserve thought the output gap was -10% during the recession that followed the oil crisis, and so kept monetary policy loose.

But it later became clear that the oil crisis was a “supply shock”, which resulted in a great deal of spare capacity being rendered obsolete (effectively destroyed) as businesses began to adjust to much higher oil prices. So overall levels of spare capacity, and potential GDP, were lower than assumed. Indeed, it was later estimated that the economy had been operating at full capacity as it entered the oil shock, so loose monetary policy caused inflation.

It could be a similar story this time round. Deutsche Bank says that US growth over the past few years was artificially ramped up by cheap credit. Potential growth was thus overstated. The unsustainable growth of recent years led to large amounts of capacity being built up – notably in the residential construction and financial sectors. This is now obsolete because the unsustainable credit-driven demand underpinning it has evaporated.

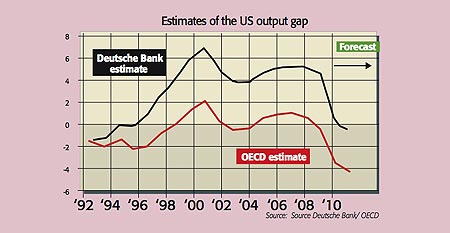

With this capacity gone forever, overall capacity and hence the output gap are smaller than assumed. Deutsche calculates that the US output gap in 2010 will be a mere -0.7%; and in the eurozone, it could be -2.4% next year, compared to the OECD’s estimate of -6.6%. So the risk of inflation, it concludes, is higher than investors think.