Eastern Europe is in serious trouble – and the eurozone’s not much better off. Can the euro survive? John Stepek and Jody Clarke report.

Last year was a tough one. But 2009 is shaping up to be worse. Already, global markets have hit fresh lows below last year’s troughs. But while collapsing markets and corporate bankruptcies will be a big theme this year, there’s an even bigger threat arising – that of entire countries going bust. As Jonathan Compton of Bedlam Asset Management puts it in the group’s latest annual report [pdf]: “The area that concerns us most is government bond markets, where several could fail before the end of 2010… such national implosions are more regular than appreciated, but will still cause panic.”

Many countries are deeply indebted, of course. Britain and America are wrecking their public finances with attempts to prop up bust banking systems and collapsing housing markets. But for now, the prime candidates for sovereign debt collapses are in Europe.

Eastern Europe’s big problems

Europe has two main problems. The first is the countries of central and eastern Europe (CEE). It’s a mistake to lump all these together as one basket-case bundle – several CEE economies are in better shape than their Western peers (see below) – but in a nutshell, as Ian Campbell says on Breakingviews, “eastern Europe is another burst bubble”.

“Far too much foreign money flowed into the region, rushed there by western European banks, keen to establish a presence and to profit from the region’s potential after its emergence from communism.” All that added credit saw house-price bubbles form across the CEE. But as with everywhere else, credit is now tightening up – particularly as the parents of those foreign banking divisions come under pressure – and foreign investment is bailing out of the region.

Countries with free-floating currencies, such as Poland and Hungary, have seen their currencies slump, driving up the cost of foreign-denominated mortgages for hapless homeowners. Average growth in the CEE region fell to 3.2% in 2008, from 5.4% in 2007 – this year it’s expected to shrink by 0.4%. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has already had to bail out several countries in the region and deals with others are being struck. “I’m expecting a second wave of countries to knock at the door,” says IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Meanwhile, the government in Latvia has collapsed. In short, eastern Europe’s woes “have all the hallmarks of the kind of emerging markets crisis that until now was confined to Latin America or southeast Asia: collapsing currencies, reversing capital flows and markets speculating on government default”, as Stefan Theil and William Underhill put it in Newsweek.

“Very simply, eastern Europe has become Europe’s version of the subprime market”

That’s certainly a pity for the eastern Europeans. But why should western Europe worry? Because its banks are behind most investment in the region. Stephen Jen of Morgan Stanley reckons eastern Europe has borrowed $1.7trn in total, and has to repay or roll over $400bn of short-term debt this year, reports Ambrose Evans-Pritchard in The Daily Telegraph. And now western banks exposed to the CEE face “hard landings”, reckons credit-rating agency Moody’s. “Very simply, eastern Europe has become Europe’s version of the subprime market,” says Robert Brusca of FAO Economics in New York.

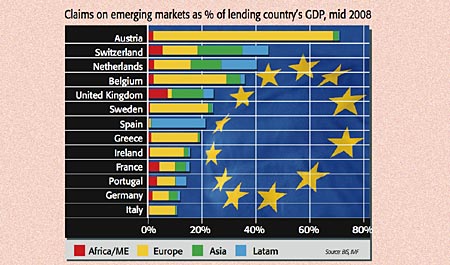

The eurozone country most vulnerable to this ‘subprime’ collapse is Austria. According to UBS, total “financial system claims on eastern Europe as a whole” are equivalent to 67% of Austria’s GDP, or €230bn – “an extreme level by any standard”. The Austrian government has already injected €1.9bn into Erste Bank, but a complete collapse in eastern Europe could put a real question mark over Austria’s ability to stand behind its banking system. Belgium and Sweden are also heavily exposed, with exposures of 27% and 22% of GDP respectively. Greek and Italian banks are also vulnerable, reports Pritchard.

This is very bad news for already fragile European banks. As Niels C Jensen at Absolute Return Partners points out, European banks in general are more heavily leveraged than US rivals, due to even more lax regulation. In fact, “Citibank has calculated that it would only take a cumulative increase in bad debts of 3.8% in 2009-2100 to take the core equity tier 1 ratio of the European banking industry down to the bare minimum of 4.5%. By comparison, bad debts rose by a cumulative 7% in Japan in 1997-1998. One can only conclude that European banks are very poorly equipped to withstand a severe recession.”

Trouble within the Eurozone too

The threat of CEE debts derailing the likes of Austria is one issue – on its own, it would probably be painful, but possible to handle. But it comes at a time when many of the Eurozone’s western members are already in deep trouble. The recession is taking its toll on every part of the world – the euro economy as a whole shrunk by 1.5% in the fourth quarter – but among the most vulnerable are the unflatteringly acronymed PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain), which account for 35% of the eurozone’s GDP.

These countries already have to pay more than Germany to borrow money. This reflects the fact that their economies are in such trouble that the market is concerned they may default or leave the eurozone. Ireland’s story is typical (see below), and not so different to that of its CEE counterparts. The country enjoyed a property bubble, driven by unsuitably low Eurozone interest rates and hefty amounts of foreign investment. But wages have soared, labour costs become uncompetitive, and now that the bubble has burst, it faces a severe downturn – one serious forecast is for house prices to fall by 80%, for example.

The route of sovereign debt default is not one that ends well

Membership of the euro prevents such countries going down the traditional route of devaluing their currency to boost exports while inflating away debt. So they face a long, slow, painful process of reform and public spending cutbacks. That’s tough at the best of times – and in the middle of a slump, it’s political suicide. But the alternative, leaving the euro, is no easy option either. The European monetary affairs commissioner, Joaquin Almunia, this week insisted that nobody would be “crazy enough” to leave. Julian Pendock of Senhouse Capital agrees. Any country that left the euro would see whichever new currency it adopted slide against the single currency. That’s a problem, because all of its debt would still be denominated in euros. As Pendock puts it, “gains in competitiveness would swiftly be offset by higher interest payments, negating any advantage”.

In this case, a country would plunge deeper into a deflationary spiral (as the value of its debt soared). Alternatively it could effectively default on its debt, by passing a law converting outstanding euro debt into the new domestic currency. But as Pendock says, “the route of sovereign default is not one that has ended well for other countries. Argentina has never been able to re-emerge as anything other than a ‘basket case’ since its first modern default in the 1940s.”

So what’s next for the euro?

Of course, any countries leaving the euro would also reflect badly on the single currency’s sustainability. So as fears grow, Almunia has been forced to insist that the EU has a back-up plan to save troubled euro members from having to go to the IMF, although he hasn’t revealed what it is yet. One option is to issue eurobonds through the European Central Bank. All member states would be liable for these, so the PIIGS would see their borrowing costs fall, drawing on the credibility of the likes of Germany, which would have to put up with higher borrowing costs. This means that the more creditworthy states subsidise the least creditworthy, but it keeps the whole euro project together. Certainly, both Almunia and German finance minister Peer Steinbruck have hinted vaguely that the idea of eurobonds is a possibility.

But as Sebastian Dullien at the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin tells The Economist: “If you want to stir anti-European sentiment, a European bond is the way to go.” It all boils down to the conflict between “idealism and nationalism”, says Simon Heffer in The Daily Telegraph. British taxpayers rightly resent being tapped to bail out British banks such as RBS. How will German taxpayers (it will be them more than any other group who are expected to cough up) feel about having to pay up for Ireland’s amateur landlords, or Spain’s unemployed builders?

Despite the fine talk at summits, there’s lots of evidence that nationalism is winning out when politicians are faced with the task of pleasing their own electorates or maintaining European solidarity. French president Nicolas Sarkozy has tried to suggest that bail-out plans for car makers be tied to measures preventing them from building factories in places such as the Czech Republic. The Spanish government has launched a ‘buy Spanish’ campaign. And there was the infamous ‘British jobs for British workers’ sloganeering by our own Gordon Brown. “A genuine assault on the European single market is brewing,” warns Gideon Rachman in the FT. “The threat over the next year will be the disintegration of the EU.”

“The threat over the next year will be the disintegration of the EU”

If Europe can’t agree on how to bail out fellow Eurozone members, then how much harder will it be to save troubled CEE countries? Hungary (admittedly, not backed by larger economies such as Poland) called for a €180bn rescue fund for the region, claiming there was the risk of a “new Iron Curtain” splitting west and east. The idea was rejected in favour of taking a ‘case-by-case’ approach, a decision that only served to push CEE currencies lower against the euro. More pertinently, how many of their weaker peers can the major economies afford to save? As Nouriel Roubini tells Time, “if Ireland or Greece go bust”, that’s one thing. “But if you have to rescue on top of them Austria and Italy, Portugal and Spain, and Belgium and the Netherlands, then that is not going to be possible.” In the longer run, of course, political paralysis may be the best thing for the Eurozone. While Britain and America build up bigger future problems by printing money, the European countries in the greatest trouble will be forced to face up to the changes they have to make to become more competitive, now that the route of devaluation is no longer easily open to them. It is possible that the number of countries in the Eurozone might shrink and expansion plans slow. Any survivors will be a tighter-knit group, better suited to a common currency. But for the forseeable future, the region faces a rocky ride, and that means the currency does too.

So what does this mean for investors? For now, the dollar will remain the ‘go-to’ currency as people rush for the ‘safety’ of the global reserve currency. The British economy’s weakness means sterling is no safe bet, but sterling investors who want to bet on the euro continuing to fall against the dollar can spreadbet, using a provider such as IG Index or City Index. Of course, with all currencies looking vulnerable, another good bet is gold. It’s fallen back after becoming over-exposed in recent months, but we’d be amazed if this was the end of its bull run. You can get exposure to the gold price via an ETF such as ETF Securities Physical Gold (LSE: PHAU).

Are there beacons of hope in the east?

Eastern Europe is submerging under the weight of its excess debt, not to mention capital flight as investors rush to cover investment losses closer to home. Hungary, Latvia and Ukraine have all sought IMF help to shore up their rapidly shrinking economies. Poland’s zloty has fallen by 28% against the euro in the past six months, Hungary’s forint by 21%, Romania’s leu by 18% and the Czech koruna by 12%.

But the east is not a uniform block. There is a world of difference between Slovakia, fast becoming Europe’s car-manufacturing hub, and Hungary, where a currency crash could topple the entire economy. In terms of stability, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovenia are by many measures faring better than countries in ‘old Europe’. Poland has a large domestic market to buffer outside shocks, while Slovenia and the Czech Republic have lower debt to GDP ratios than Spain, Greece and Italy.

The Baltic States, Hungary and Ukraine look to be in the most trouble, with all except Estonia likely to shrink by double-digit figures this year. The Latvian government has already fallen, while there seems no end in sight for Ukraine’s political and economic woes. Meanwhile, Hungarians are paying the price for switching their mortgages and personal loans into foreign currency, now that the forint is plunging – over 60% of loans and mortgages are in foreign currencies, says The Daily Telegraph, driving up interest payments – bad news at a time when 100,000 people are expected to be made unemployed this year.

But perhaps the best illustration of the gap between the strongest and weakest eastern European countries came at an emergency summit in Brussels at the weekend, where Ferenc Gyurcsany, the Hungarian prime minister, warned of a “new Iron Curtain” if eastern Europe was not bailed out of its difficulties. But Jacek Rostowski, Poland’s finance minister, was not in favour of a blanket bail-out fund, warning that if budget deficits were raised and the public debt expanded, “we would end up like Hungary”.

The Celtic Tiger: dead and buried

Just two years ago, Ireland was the eurozone’s second fastest-growing economy. Today, it’s the fastest shrinking – Goodbody Stockbrokers reckons the economy will shrink by 6% this year. Fears over the country’s ability to pay its debts mean the Irish government is being forced to to pay around 2.5 percentage points more on ten-year bonds than Germany, reports Bloomberg. Meanwhile, credit default swaps (CDS – effectively, insurance against a creditor defaulting) on Irish bonds peaked at 399 basis points last month, a sure sign the markets are losing faith in the Irish government’s ability to pay its bills. Already the budget deficit is heading for 13% of GDP, against an expected 4.4% average for the eurozone in 2010 – EU rules dictate that deficits should never go above 3% of GDP.

The good news is that the Irish government, under the surly direction of prime minister Brian Cowen, has begun taking action. The bad news – for the Irish people at least – is that it will hurt. Through a combination of higher taxes and spending cuts, Cowen plans to restore balance to the public finances by 2013, and to improve banking regulation. He aims to broaden the tax base to include many of the 40% of workers who currently pay no tax, while slicing €1.4bn off the public sector by introducing a pension levy.

Needless to say, many are not happy about this. After watching various dubious shenanigans unfold at Ireland’s banks, 120,000 people, mainly civil servants, took to the streets of Dublin last month in protest. Many were incredulous that they’d have to take a 7% pay cut while Ireland’s very own Fred the Shred – ex-chairman of the now-nationalised Anglo Irish Bank, Sean Fitzpatrick – could be walking away with a €25m pension pot. Earlier this year, it was revealed that he’d failed to disclose an €87m personal loan over a six-year period. Meanwhile, consumers are slashing back on spending – the Drinks Industry Group of Ireland reports that Irish alcohol sales are now at their lowest since 1997, while bookies are set to shut down 250 betting shops by the end of next year, reports Bloomberg.