With Britain on the verge of being bankrupt, encouraging the banks to increase lending is a wrong-headed and risky move, says James Ferguson.

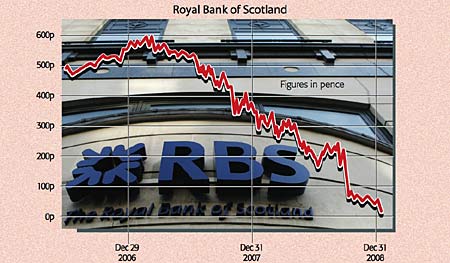

Saving the world is tougher than it looks. Gordon Brown may have hoped his first shot at rescuing the banking system, by pumping £37bn of taxpayers’ cash into the UK’s banks, would be enough. But it wasn’t. Galvanised by record losses at Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), last weekend the Treasury came up with a raft of measures to shore up the banks further. But the government’s confused approach is just making things worse – you only have to look at the market reaction to see that. Banking stocks have plunged. RBS, Barclays and Lloyds were hit particularly hard, but even HSBC, a global giant with £580bn in worldwide deposits, wasn’t safe, losing over a fifth of its value. So what’s going on?

The biggest fear for bank investors is the threat of nationalisation, which would wipe out shareholders. So the Treasury’s decision to turn the £5bn of preference shares (prefs) it owned in RBS into ordinary shares, raising its stake to 70% from 58%, rattled them badly. Certainly the 12% dividend on the prefs made it hard for RBS to expand lending – but that could have been dealt with by cutting the pay-out. Instead, shareholders suffered a savage dilution all without the benefit of any extra capital being provided.

Now the remaining big banks fear the worst. If the government can implicitly renege on its agreements while diluting shareholders at will, that shows the state is getting very close to dictating terms. The market now assumes we’re just one small step away from the state allocation of credit – full nationalisation is just one more weekend meeting away. The fact that the government has also imposed an unrealistic obligation on RBS to increase lending by a further £6bn disturbed the market even more. Either the banks’ problems are fixed – in which case they’ll lend again freely without the government forcing them to – or more likely, they’re not yet, in which case lending more money could prove fatal.

Nationalisation or not?

But while the government seemed to lurch towards full-scale nationalisation on one hand, on the other it announced an unconvincing rag bag of new ideas that mostly simply extended or supplemented earlier moves. Take the plan to offer capital and asset protection to the banks by insuring them against extreme losses. The aim is to underwrite the losses the banks might make on the investments “most affected by current economic conditions”. But it’s not clear how widespread the scheme will be or what it’ll cost to take part, which merely clouds things even further. Will it be significant enough to warrant optimism about the banks’ potential downside or not? Or will the terms be too onerous to be attractive to the banks?

The Treasury is also extending the liquidity facilities it had already made available to the banks, and also plans to let the banks’ capital ratios slide as losses come in, “facilitating continued lending”. So the Treasury actually wants to push banks into lending more, even as their capital position becomes dangerously precarious.

The Bank of England has also been given an initial £50bn of our money to go out and buy corporate bonds, asset-backed securities and the like – a form of “quantitative easing”. The claim is that this will “reduce illiquidity”. But this doesn’t stack up. Buying paper out of the market if anything will increase illiquidity by reducing supply. What it will do is narrow spreads between government bonds and high-quality corporate debt. What the government actually wants to do is to force investors to take more risk by pushing yields on gilts and “safe” company debt so low that they have no choice but to buy riskier assets.

Meanwhile, Northern Rock is to stop scaling back its mortgage book. This may seem a sensible idea, but Northern Rock has too many unfair advantages over the private-sector banks. In economist-speak, it is likely to crowd out the other banks, making any problems they may be dealing with worse. In nationalisation terms it’s all-in or none-in; you can’t have a half-way house.

Our banks can’t afford to lend

The problem is that the government still seems to believe that bank write-downs are all down merely to illiquid and wrongly priced securities markets. If we can just peg a floor to such securities, the banks can get back out there and lend like it was 2007. This is scary stuff. The government still doesn’t realise that we’re not facing a liquidity crisis – it’s not just a case of freeing up lending markets. We’re facing a banking crisis – our banks may not have enough capital to survive.

Banks don’t want to lend, because they’re fearful that the losses they may take during this recession on the loans they’ve already made could wipe out their capital bases. Encouraging the banks to “increase lending” at this stage in the cycle is like telling them to jump off a cliff. Think about it. Even if you were swimming in cash, would you lend money to a buy-to-let landlord right now? Or back a friend to open a new restaurant in the City? It would be madness. More to the point, who would want to borrow more money to set up such a business right now? So regardless of what the government tries to do, banks will shrink lending to the private sector. And this will happen even if they’re nationalised.

We know this because there have been 117 separate occasions since the early 1970s where nations have seen their entire banking system capital wiped out. The Bank of England has studied 33 in detail, while Harvard Professor Ken Rogoff and his colleague Carmen Reinhart have analysed 15 developed-world bank crises. In no cases did banks increase their private-sector lending – quite the opposite. Once banks have over-extended themselves to such a degree, they work very hard not just to stop lending, but to retract existing loans back from borrowers. This is what triggers the rapid rise in bankruptcies that recessions involving banking crises are famed for.

What else do previous banking crises teach us? For one thing, we’re in for the long haul. On average, banks take 4.3 years to mend their balance sheets, even with full government support or ownership. The direct costs of recapitalising banks, if there’s a currency crisis too (as there has already been in sterling), is nearly 18% of GDP. That’s £250bn, compared to the £37bn the government pumped into the banks ahead of this weekend.

We know that government debt tends to virtually double in the first three years of the crisis, as tax receipts fall, social security payments rise and public spending to alleviate the credit contraction soars. Yet real economic growth still drops an average of 9.3% over the first two years and remains sub-par for almost another three. Unemployment, of course, shoots up as firms cut back and many more are tipped into bankruptcy. On average, unemployment grows by seven percentage points – but it’s worse in developed nations. That suggests that in the UK and US the unemployment rate might exceed 12%. It’s already almost 7% in America. With so many out of work, the housing market can be expected to fall for six years and lose 36% in real value.

What needs to be done now

First of all, the government needs to acknowledge how serious this situation is, and forget about the illogical lunacy of trying to solve an over-indebted borrowing binge with more borrowing. Pretending things won’t get a lot worse before they get better, implying that recovery is just around the corner, and that the day can be saved if only the banks get back to 2007 levels of lending, is doing us all a disservice.

The banks’ problem in a nutshell is that they have too many risky assets for their inadequate capital bases. Either the banks have to run down those risky assets (meaning bankruptcies, unemployment and recession), or the government has massively to boost their capital bases (diluting the existing owners of capital – the shareholders – to near zero). This approach is nationalisation. A more palatable option, the good bank/bad bank split – which worked for the Nordic countries in the early 1990s – is essentially nationalisation, but instead of government capital backing all the assets, the government backs a ring-fenced group of the worst assets (the ‘bad’ bank), leaving a smaller amount of assets (and potential losses) to be backed by existing capital.

The capital to asset ratio is improved, just as it is in a nationalisation. The government capital commitment is the same as a nationalisation. But this way a private-sector entity, now adequately capitalised, remains. It’s just a way of hiding how generous the government has been in the terms of its aid because no one gets to see what the capital commitment will be.

Meanwhile, as banks are licking their wounds, the government must minimise the impact on the wider economy by pursuing monetary policy aims (such as credit provision to employers, home buyers and entrepreneurs), but using fiscal policy channels (by setting up state credit providers and mortgage lenders on a temporary basis). Unfortunately, it looks like the government may need a few more attempts at saving the world before it works this out.

Could the bail-out bankrupt Britain?

It’s not often that Wall Street falls as far as it did on Tuesday (the S&P 500 financials index plunged almost 17%) on events in the UK, writes David Stevenson. But the British banking sector’s woes succeeded in causing by far the worst-ever presidential inauguration day sell-off. Why? Because fears are spreading around the world that the British banking system is, in all but name, bust. And that in bailing it out – ie, simply shifting the banks’ bad assets into the public purse – the country itself could be brought to its knees. The cost of insuring against a default by gilts (UK government debt) has risen by 25% within the last week.

A British government default impossible? Think again. We have form. “Britain came off the gold standard in 1931 and sterling devalued by 28%. The economic crisis that followed marked the end of the UK as a global power,” says the FT’s Lex column. “It also led to an effective default on almost half the national debt, which was restructured into bonds still outstanding”. In other words, we’re still paying for the last time we went bust. There are already scary parallels with the present day. Since the middle of 2007, the trade-weighted value of the pound has fallen by some 27%.

And no one knows exactly what the toxic assets on British banks’ balance sheets are worth. Among others, new Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) boss Steven Hester has stressed that banks must “fess up” to the size of their problems. But “they should be careful what they wish for”, says the Evening Standard’s Anthony Hilton. “Asset values have dropped by at least 25% across the board”, with some falls much greater. The most recent financial accounts of the big four British banks – RBS, HSBC, Barclays and the Lloyds Banking Group (the product of the Lloyds TSB/HBOS merger) – show combined net assets of £6trn. Yet since the crisis began in late summer 2007, they have made write-offs totalling ‘just’ £67.4bn, ie, little more than 1%.

On the other side of their balance sheets, these British lenders have racked up $4.4trn of foreign liabilities, twice the size of the entire economy. In short, the UK banking system is on the brink. So the British government “faces an excruciating choice”, says The Daily Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, “it can’t let RBS and its fellow mega-banks go to the wall, yet it risks being swamped by their massive foreign debts by opting for full nationalisation”. Further, Britain has foreign reserves of under $61bn, less than Malaysia or Thailand, so “the mismatch is perilous”. There are frightening parallels with Iceland, which was ruined by the antics of its three big banks. These built up foreign liabilities equal to 900% of GDP, which the government lacked the reserves to match.

“But Iceland at least had the luxury of letting its banks default”, says Evans-Pritchard, “by refusing to honour foreign debts and so shifting losses onto the rest of the world”. If the government were to let our banks fail, those $4.4trn of foreign liabilities – eight times Lehman Brothers – would blitz the City’s standing. “The UK can’t go down that route because it would set off an asset price death spiral”, says Marc Ostwald at Monument Securities. “The Western banking system is already on life support. That would turn it off altogether”. Yet if the state has to take over the British banks, the UK’s cherished AAA credit rating is set to suffer. Spain has been relegated from AAA to AA+, even though its public debt is a much lower share of GDP than ours. “If Spain can get downgraded, the risks for the UK are self-evident”, says GFC Economics’ Graham Turner. “The increase in the UK gross public-debt burden – 11.8% in just one year – is troubling. The market rightly fears the long-term fiscal costs of a collapsing banking system.”

So far, Standard & Poor’s has denied talk that it will soon cut Britain’s top-notch ranking, which even survived the 1976 bailout by the IMF. But the IMF itself is clearly queasy about Gordon Brown’s latest ‘rescue’ attempt. “Market confidence in the [banking] sector has eroded to such a degree that it’s not clear whether these measures will bring a material improvement – full nationalisation of some banks remains a possibility”. Not only would a UK debt downgrade raise the cost of raising money via gilt sales, it would be the next step towards national bankruptcy. No wonder sterling, possibly the best barometer of the nation’s financial health, is in complete freefall.

What does all this mean for investors?

First off, the British economy is going to be in the doldrums for a long time. While we won’t be the only ones – both the US and Europe have serious banking problems, while Japan is in recession too – sterling is particularly vulnerable. It doesn’t have the reserve status of the dollar, the scale of the euro, or the relatively strong economy backing the yen. So we don’t see much scope for sterling to strengthen in the long run, beyond short-term rebounds between falls. That suggests that for sterling investors, foreign-currency-denominated assets aren’t a bad bet.

Gold has long been a MoneyWeek favourite and is currently regularly breaking records in sterling terms, even though it’s still well off its dollar high of more than $1,000 an ounce set in March last year. You can buy physical gold from a bullion dealer, or get exposure via a London-listed exchange traded fund such as ETFS Physical Gold (LSE:PHAU).

As for the stockmarket, avoid banks. This should almost go without saying, but there are still some investors who see big banks trading at near-penny stock prices and think “bargain”. Don’t be fooled – they’re cheap for the very good reason that no one knows what they’re worth or what the future holds for them.

Investors should instead look at cash-generative companies with solid balance sheets and decent yields. Oil majors such as BP (LSE:BP) and Royal Dutch Shell (LSE:RDSA), and pharma groups such as GlaxoSmithKline (LSE:GSK) look solid bets, and have the added advantage for British investors (assuming sterling keeps falling) of accounting in dollars.

As for broader market exposure, again, we’d stick with Japan. The market looks cheap, and although it has fallen substantially in yen terms, in sterling terms it’s barely changed in the past year. Should the Bank of Japan decide to start selling yen to weaken its currency the chances are that the likely boost to the stockmarket would offset any currency impact, particularly for sterling investors. One way to gain exposure to Japan is via the iShares MSCI Japan fund (LSE:IJPN).