If you’re going to put money into any stockmarket today, it should be Japan’s, says John Stepek.

Here at MoneyWeek, we’ve been fans of Japan for a long time. But unlike, say, our fondness for gold, or our scepticism about property, it’s not always been the most rewarding relationship.

Japan’s market did well in 2005 and 2006, but it languished in 2007, and dived in 2008 (along with everything else). Sterling investors wouldn’t have felt the pain as keenly as locals – the Topix index was pretty much flat in sterling terms that year, compared to a near 40% fall in yen, which just goes to show how weak the pound was. The stockmarket has rebounded since March, just like every other market around the world, but it’s still only clawed its way back to levels last seen in mid-2003, despite a 25% or so rise from its March low.

And even though it’s now 20 years since Japan’s bubble burst, in many ways the state of the economy has arguably never been worse. The country’s reliance on exports means it has felt the pain of the global recession more keenly than most. With Western consumer demand down, businesses are cutting production, which means lower wages and fewer jobs. That insecurity in turn has hit domestic spending. In the first quarter of this year, GDP shrunk at an annualised rate of 15.2% – the largest fall on record, and the fourth quarter in a row that the economy has shrunk. That makes the 6.1% fall in America over the same period seem almost respectable.

The fact that this atrocious figure was, in fact, better than expected goes to show just how bad things are. Every country in the world is suffering; butas one Japanese central bank member, Miyako Suda, put it in March: “The Japanese economy has tumbled off a cliff into a deep valley and is now wandering around in the mud in dense fog.” It’s the sort of wonderfully honest comment you’d be hard pressed to imagine coming from the lips of the permanently optimistic Ben Bernanke, or even from our own rather more critically inclined Mervyn King. It seems that Japan has been in the doldrums for so long that not even its central bankers worry about “talking the economy down” anymore. However, we still think that if you are going to invest in any stockmarket today, it should be Japan’s. Here’s why.

The worst could be behind Japan

As we noted above, first-quarter GDP was horrendous. But that’s in the past now, and prospects for the second quarter are much brighter. In fact, Julian Jessop at Capital Economics reckons Japan might even see a return to growth – one of the first major economies to do so.

How can this be? Well, on the one hand, global demand has tanked, but if anything, companies have slashed supply even more rapidly than demand has fallen. Leo Lewis in The Times points out that big companies such as Panasonic and Toyota “have been uncharacteristically ruthless about shutting factories and slashing staff headcounts”. Global car sales in the first two months of 2009 fell 25%, but Japanese car production fell by 50%, Richard Jerram of Macquarie Securities tells The Economist.

That means that as the collapse in global trade slows – as it has to – a rebound in activity is inevitable as factories have to restart production to keep up with demand. Now it’s unlikely that we’ll see demand for manufactured goods return to the credit-bubble-fuelled levels seen before. But as Robert Brooke points out in the Halkin newsletter, Japanese manufacturers “will be among those that cope best with the adjustment” to this newly frugal world, “probably by a combination of restructuring their own businesses and taking market share from weaker competitors”. That’s because they’re used to hard times. “They have done it repeatedly over the past 30 years, previously in response to protectionism and currency moves, now prodded by sharp changes in demand.”

There are also some hopeful signs on the political front. Since 1955, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has been in power for all but 11 months. The current prime minister, Taro Aso, has proved an uninspired leader, and in all, Japanese politics has disappointed since the departure of popular pro-reform prime minister Junichiro Koizumi, who was in power between 2001 and 2006. But change is on the way – the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) now looks set to win full control of the government after elections, which must be held by September. This is good news, because as Christopher Wood of CLSA points out, “the long overdue reform of Japan’s domestic economy is only going to happen if there is an end to traditional LDP rule”.

The DPJ, meanwhile, has just elected Yukio Hatoyama as its leader, replacing the outgoing Ichiro Ozawa, a former LDP secretary-general. In his acceptance speech, reports Martin Hutchinson on Breakingviews, he emphasised “sweeping away wasteful uses of tax money” and “moving from bureaucrat-led to citizen-led government”. If he can “combine Koizumi’s free-market approach with decentralisation of Japan’s ossified bureaucracy”, he could be good news for Japan.

However, it’s never a good idea to take hopes of political change too seriously – governments have a habit of failing to live up to expectations. In any case, none of this takes away from the fact that the world will remain in a precarious state, bumping in and out of recession for the foreseeable future. Despite a surprise bounce in consumer confidence in April, Japanese consumers are unlikely to pick up the slack anytime soon. Although they still have some savings, these are being eaten away as retired people are forced to dig into their capital by low interest rates. And you can hardly expect young consumers to up their spending now when they feel insecure about their jobs and the outlook in general, regardless of how much the government encourages them with subsidies.

And in any case, just like governments in the West, the Japanese state has taken on a great deal of debt during its ‘lost decade’ (or two), spending on various ‘stimulus’ packages that have had limited success. That’s going to have to be tackled, and will act as a drag on growth – due to higher taxes and, eventually, borrowing costs – for the foreseeable future. So while the outlook might be less grim than it has been, it’s hardly all blue skies. So why buy now?

Japan is cheap

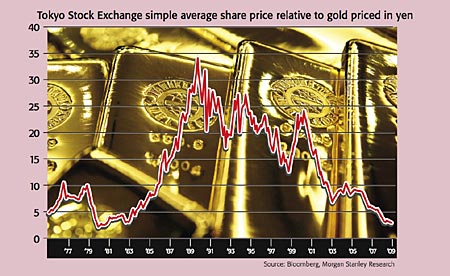

There’s a simple answer to that. Japan is cheap. Yes, some other global markets – although increasingly few after the recent bounce – offer pockets of value. But only Japan is real, dead-in-the-dirt, beaten-down, everybody-hates-it cheap, even after the recent rally. One of the most effective illustrations of just how cheap Japan is can be seen in the chart in the main picture on page 24, taken from a Morgan Stanley report by Alexander Kinmont. It shows the Tokyo Stock Exchange relative to the price of gold in yen. An ounce of gold will buy you almost the same quantity of Japanese stocks now as it would have in February 1979. In other words, in gold terms, Japan is near a 30-year low. So it’s pricing in a pretty bleak future. That’s a striking image, but it’s hardly a mainstream guide to equity valuations. But there are many more indicators of just how inexpensive Japan is, says Kinmont.

For one, Japan is the cheapest major market judged by price-to-book (PB), with the Topix trading on a PB of 1.1, against two for the S&P 500, and 1.5 for the FTSE All-Share. And small caps in particular remain very cheap by this measure (see below). What this means is that, effectively, you can buy many Japanese companies for the price of the assets on their balance sheets or less.

Judging by past experience, Japan tends to deliver the goods from this point. Kinmont looked at historic returns from the MSCI Japan Index, using three measures: PB, the price-to-cash-flow (PCF) ratio and dividend yield. He found that in previous instances when PB was below 1.2; PCF between four and six (as it is now); and dividend yield at three or more, the market has almost always made money within the next three years.

Japanese companies seem to agree that they are undervalued. Economist James Tobin (of Tobin’s ‘q’ fame) argues that if companies find it cheaper to buy new capacity than to build it, then they will do so. In other words, when stocks are undervalued, you are likely to see companies cut spending on new equipment and instead buy other firms and their own shares. And this “appears to be happening now” in Japan, says Kinmont. Over the past two years, shares have been disappearing from the stockmarket through mergers and stock repurchases at a rate of about ¥2.7trn ($28bn) a year. This suggests that businesses – who should be best placed to know – reckon that “their stockmarket valuations do not reflect the fundamental value” of their firms.

Then there’s the sheer weight of pessimism and downright dismissal of Japan, after years of disappointment. The same investors who have lined up to dive right back into the US and risky emerging markets at the first sign of a bounce are still hesitant over Japan. “At the end of a 19-year bear market, any renewed revulsion against equities should be construed as an opportunity to deploy more cash, not as a reason to embrace extreme pessimism,” as Kinmont puts it.

Morgan Stanley has a 12-month price target of 1,100 for the Topix index.It’s now sitting at around 850, so that’s around 30% higher from where we are now. They reckon the worst-case scenario is that it falls back to 800. So that’s a pretty good risk/reward outlook. In short, Kinmont reckons that 2009 will “in retrospect prove to have been a good, possibly great, time to have bought Japanese stocks”.

Japan is better placed than the West

There’s a final reason to buy Japan. And that’s because, as well as being cheap, it’s arguably among the best-placed recovery plays – regardless of whether the global economy rallies or relapses.

Several commentators – usually those who didn’t see the credit crunch coming in the first place – have taken great pleasure in pointing to the pain being felt by export-dependent economies such as Japan and Germany, implying that the Anglo-Saxon economic model of housing bubbles and unchecked borrowing and spending must be better. However, the same pundits don’t seem to realise that if – through low interest rates and the magic of money printing – the US and the UK authorities somehow succeed in winding the clock back to the debt-fuelled heyday of 2006/2007, then all those Western consumers are going to go out and buy imported goods. And whose goods will they buy? Germany’s, China’s and Japan’s. So any rebound in the Western economies will be felt, if anything, even more violently in the export-heavy economies.

Thus, if you believe the global economy is on the V-shaped recovery trail, you’ll get more bang for your buck by buying an exporter than by investing in a consumer.

If, however, as seems more likely to us, consumer demand in the West never really recovers, and America and Britain face a scenario more like that seen in Japan over the past couple of decades, then what happens? Everyone will face some uncomfortable changes. But the only real challenge for exporting countries will be to find new customers. Conversely, economies that have been built on debt, money-shuffling, and swapping properties with each other, will have to find a way to build whole new, efficient, productive industries from scratch – arguably by far the more difficult task.

If there’s a lesson to be learned from Japan, it’s that recovering from massive bubbles – and banking crises in particular – takes a very long time. Brooke points out that at the peak of the Japanese bull market in 1989, there were 19 banks. Today there are eight, and only one of those original 19 has “retained the same name and effectively the same business as 20 years ago”. The rest have gone bust, been nationalised (and refloated) or merged with others.

This experience suggests that the Western banking system may well face further trauma ahead. But Japan has already been through its pain. “This was a once in a lifetime crisis. I find it easy to believe the West must follow a similar path, but hard to believe that Japan will tread that same path a second time.” Indeed, “this probably marks the final unwinding of the great Japanese bubble”, says Brooke. For Japan, the current collapse “is only a cycle. And cycles turn.” To find out how best to profit from this one, see below.

How to buy into Japan

You can buy into the broad Japanese market easily via an exchange-traded fund (ETF), such as the iShares MSCI Japan (LSE: IJPN) ETF, and we’d be happy to do so. However, if you really want to hunt for the cheap stuff, you should take a look at small caps. Even after the recent global rally, says James Montier of Société Générale, “Japanese small caps remain among the cheapest assets in the world”. Small caps still trade at a price-to-book ratio of well below one, suggesting that, in theory at least, an investor could buy them today, liquidate their assets, and still make money.

A number of ETFs are available tracking the small-cap market. These include the iShares MSCI Japan SmallCap (LSE: ISJP); and the US-listed Wisdom Tree Japan Small Cap Dividend Fund (US: DFJ) and SPDR Russell/Nomura Small Cap Japan Fund (US: JSC).

A number of large Japanese stocks also still pass Montier’s ‘deep value’ screen. He uses four criteria, including a dividend yield of at least two-thirds the AAA bond yield, and total debt of less than two-thirds tangible book value. Stocks that meet these criteria include camera and photocopier giant Canon (JP: 7751), which yields 3%; drugs group Ono Pharmaceutical (JP: 4528), with a yield of 4%; and computer games group Konami (JP: 9766), yielding 3%.

Citigroup also has an interesting take on where Japan’s next big boom might come from. Analyst Tsutoma Fujita suggests an environment bubble might arise from this crisis, just as the dotcom bubble grew out of the cheap money policies adopted following previous crises. He reckons that global government spending on ‘green’ technologies, alongside a follow-up to the Kyoto Protocol deal on climate change, will encourage investors to pile into environmental stocks – and Japan is in the perfect position to profit. Lacking natural resources, the country imports more than 95% of its energy, which means that necessity has already made it the most energy-efficient of the developed nations.

We’re not convinced the world’s ready to blow more bubbles just yet, and Fujita’s suggestions are hardly pure plays, but if you’d like to pick up some Japanese green stocks, his tips include Honda (JP: 7267) and Suzuki (JP: 7269) for green cars, manufacturing giant Kyocera (JP: 6971) for solar power, and Sumitomo Electric (JP: 5802) for smart grid technology.