This month’s Roundtable experts are: James Ferguson, economist and stockbroker with Pali International; Ed Mead, director at Douglas & Gordon Estate Agents; Henry Pryor, CEO of PrimeMove.com; Seema Shah, property economist at Capital Economics; and John Wriglesworth, managing director of Wriglesworth Consultancy.

Merryn Somerset Webb: So John, last year you said there was more chance of Elvis being found on the moon than of a British housing crash. What do you think has changed?

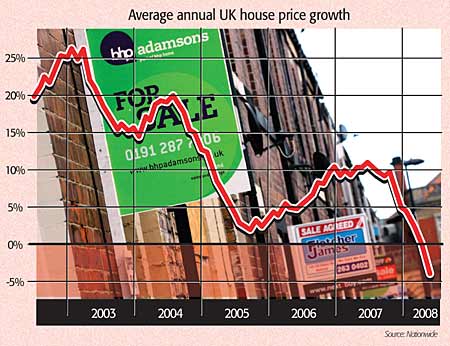

John Wriglesworth: It is purely down to the shortage of funding available for mortgage finance. This is causing the contraction in the housing market, in the same way as the expansion of funding and the relaxation of credit criteria over the last five or six years allowed house prices to go up. During the boom, most bears were fixated on house price/incomes ratios – but that seemed to be the wrong way to look at it to me. With interest rates at 5% and people being able to borrow increasingly large percentages of their income (first four times, then five, then six times by 2006), house prices were clearly just going to keep on rising to what I had thought would be a new plateau.

I believed last year that there was no reason to go back to a historic house price/incomes ratio because we are just adjusting to a new plateau created by lower mortgage costs. But what makes me very worried is the fact that the credit situation of the last five years is now being totally reversed. Now you need perfect credit to get a loan and lenders want 25% deposits, and so on. Everything that produced the boom is going into reverse. If that doesn’t change, I’ll end up one of the most pessimistic around this table.

Merryn: Do you think it can change?

John: If the Government really thumped the chest of the market with a huge liquidity injection – say £350m, rather than £50m, then yes, I do.

Ed Mead: I agree with you on the cause and effect here. None of us had really factored in the possibility of a credit crunch like this. And I think that, had the Government made a much bolder move when they talked about putting liquidity into the markets, it might have made a more significant difference to people’s level of confidence.

But now confidence is really shaken. Prices stalled in London last year in July/August when the crunch first reared its head and people started beginning to wonder what it all meant. After a bit of a stand-off, they then slashed their prices by 10% in March. That made the buyers interested. But then the buyers couldn’t get funding – so they’ve gone back into their shells. Add in oil prices, food prices and general misery, and I’d say there’s a lot further to go. Transactional volumes are likely to go to zero in the next two or three months.

Merryn: So you agree that without the credit crunch we would have no crisis?

Ed: I think that at some point we would still have seen prices off 10%-15%, given how stretched prices were, but it wouldn’t have been anything like this. I do wish the Government had done more to bolster confidence.

John: It’s just about finance. The demand is still out there. Whenever any lenders put out a reasonably normal mortgage at relatively normal rates for normal credit criteria, it sells out immediately. Such is the rush that they end up withdrawing the products in a hurry. They can’t cope with the demand for good mortgages.

James Ferguson: Nonsense. They put those mortgages out there and then withdraw them for political reasons only. If you’re a bank and you know that you are technically bankrupt (what banks like to call ‘undercapitalised’), you can do two things. You can get a capital injection and bring your capital up to the right size. Or – like Northern Rock – you can look to lower your asset base. That means deliberately trying to lose business. But the banks can’t be seen to be doing this – Gordon Brown doesn’t look kindly on banks refusing to lend to higher-risk customers.

So, what they do is say, “We’re trying, but every time we put out a good price we have to withdraw it within 24 hours because of the rush.” Yes, of course, there’s a big rush right now because virtually all of the banks have been pulling their products. But when was the last time someone issued a product and then pulled it because of the rush? What they are trying to do is to make a show of having offered good rates, while not actually having to lend at those good rates.

John: So why don’t they price mortgages properly – for the risk? If there is so much demand for a 95% deal at 6%, why not try and sell it at 8%? I asked a lender this – why it doesn’t effectively price the rush out. It said the Financial Services Authority (FSA) doesn’t want it to, but also that by doing that it opens itself to being downgraded by the credit agencies who don’t understand how risk is priced at all. But what this means is that the whole market is now log-jammed and rationed, and that we are in a confidence unwind that could lead us into recession.

James: That will lead us into recession. People are still saying that there is nothing to worry about because the economy is still strong and there’s no unemployment. But that is the wrong way around – housing always goes first.

Seema Shah: The Bank of England tells us it doesn’t see a very strong relationship between consumer spending and house-price growth. But if you look at even a very basic chart, there is in fact a very strong relationship. A lot of consumer confidence is based on rising property prices. So when they fall, you just tend to spend less – you go into saving mode.

James: The thing with a crash is that you never know what’s going to kick it off. You need a catalyst. Sometimes it’s just affordability – people just can’t afford to go any further. Sometimes it’s a natural peak, where the marginal buyer says no, he’s not interested. And sometimes the lender says we can’t do it. Like this time. So the crunch has been a catalyst, but that doesn’t mean it has been the cause. You have to remember that the environment we are in now is the normal one. It is the last five years that have been abnormal.

In the old days, banks worked on making margins on their lending of 2%-3%. A year ago they were making well under 1% a lot of the time – but 2% is the norm. And that’s what we are going back to. You know most people can still borrow at most lenders’ variable rates – it is just that those prices are higher than they are used to. It isn’t actually a crisis, just a return to normal lending, and that is what the banks want – at least while they rebuild their balance sheets. The banks don’t want much new business, and they want what business they take on to be really high quality, and to be charging the maximum possible.

Ed: So how long will this rebuilding take?

James: It’s hard to know. It took 15 years in Japan after the crash in the 1990s. But that was slow. When it happened in Sweden, they took a radical approach and sorted it out within five years.

Ed: But you know none of this should mean that people don’t buy at all. People should stop worrying about values of properties and just ask themselves four basic questions. Can I afford my mortgage now with interest rates the way they are? Can I afford it if mortgage rates go up a couple of points? If values drop a bit, can I afford to live in it for the next five years on that basis? Is it going to be big enough for me and, if not, can I possibly rent it out? If the answer to those four questions is yes, then why not buy?

Merryn: There’s another question. Is it cheaper for me to rent the house next door than it is for me to buy this one?

Ed: That’s not how most people think. They want to be on the ladder. The recent shift towards renting is just about waiting for a bargain. Most people want to live in their own house.

Seema: But why would you buy today if it’s going to be cheaper in two years’ time?

James: Particularly when, even now, we are miles away from real affordability. Debt service burdens for new buyers are still huge, and as for the average first-time buyer – ten years ago he was 25. Now, if he exists at all, he is 35.

Henry Pryor: It seems amazing to me that there are still people out there pretending that things are fine when they just aren’t. It’s totally irresponsible for commentators to do this – it leads too many people into problems. All those who have persuaded people to borrow money they can’t really afford, on interest-only mortgages, are at fault here – they leave people reliant on inflation to pay off their debts. And worse, of course, are all the property clubs who have drawn people in on the promise of ever-rising prices.

James: Most of us here have spent a long time trying to persuade people not to get into trouble with property clubs, such as Inside Track. But these clubs all used unsophisticated arguments with veneers of sophistication, aimed at unsophisticated people who weren’t sufficiently informed.

Merryn: Raising a moral issue?

James: Well yes, but there doesn’t seem to have been any real understanding of how horrible all this is going to become. Look at it like this. In 2003, interest rates were 3.5% and there was no premium to speak of on your mortgage rate. Now interest rates are 5% and there’s a 2% point premium. So interest rates have effectively more than doubled. On a straightforward calculation, that alone tells you that the value of your asset should half.

John: It’s pretty bad. I have to say I agree with James about the possibility of a 50% fall. But if the easy credit terms of the last five years continue to unwind completely – if we’re back to people only being able to borrow three or four times their income – then I can’t see anything other than house prices going back to what they were, because where then is the demand coming from? And house prices are up – what – 100% in the last five years?

Merryn: So the only property bull we could find for this Roundtable thinks prices are going to fall by 50%!

John: If lenders don’t go back to lending. That ‘if’ is so important. If the Government put a bit more into liquidity, it might not happen.

Henry: It would be outrageous if they did.

John: Why?

Henry: Because the free market allows things to go down as well as up – you can’t change that.

James: There was actually a very interesting free-market distortion in this cycle with buy-to-let. You can’t short property, but buy-to-let suddenly meant that you could gear up. It used to be that if you liked property, you got to buy one house. With buy-to-let loans, you could get 20 – but no one who disagreed with you could go short. So you had this massive overinflation distorted by interest-only mortgages being given out to people who, despite huge debt levels and not being owner/occupiers, weren’t even considered high-risk.

Henry: Now we’ve got a million official buy-to-let mortgages and, surely, another couple of hundred thousand that just aren’t classified as such.

James: Buy-to-let is going to be so horrific because the buy-to-let guys have all fallen for the usual nonsense about being in it for the long term. They aren’t, of course, and frankly there won’t be any prizes for holding out before you sell. Best do it first. Those who panic now won’t suffer as much as those who panic later. For all those buy-to-lets to find buyers, prices have to come down to a level at which first-time buyers can afford them. And that is a long way down.

Professor Stephen Nickell, who used to be on the Monetary Policy Committee, used to say that first-time-buyer house-price multiples were only 3.5 times salaries. But look at the average house price and that suggests first-time buyers are earning £40,000 or £45,000. They are. But all that tells you is not that houses are affordable, but that you have to be twice as rich as the average person to buy a house!

John: That’s exactly true. The likes of Halifax and the Council of Mortgage Lenders use the salaries of people who actually buy houses when they look at affordability. So if the average first-time buyer is earning £40,000, then obviously the ratio of mortgage repayments to income looks all right. But that is very misleading. What it hides is the fact that for most people of first-home-buying age, affordability is terrible.

Merryn: So what next?

James: One other thing in the statistics, which we are about to re-learn again, is that at the beginning of a crash, prices don’t look like they are coming off that much. The first casualty of a house-price crash is transaction volumes. Sellers hold out, but buyers won’t pay. So only a few deals go through and prices ostensibly don’t fall off much: the indices don’t record the buyers who stand on the sidelines, or the sellers who won’t get real.

Ed: But we’re coming to the end of that bit now. It seemed to me that the stand-off was almost over in April, with most sellers prepared to sell at prices the buyers looked like they would pay. But then those buyers found that they couldn’t get the finance. We got the offers, but not the exchanges.

Merryn: So the stand-off continues?

Henry: Absolutely. I’m not seeing sellers giving in yet. In general, I see them refusing low offers. Agents are tearing their hair out trying to get deals done, but their vendors are still unrealistic in their expectations.

Merryn: Ed, do you think it is possible for house prices in, say, Chelsea to end up falling by 50%?

Ed: I think that’s unlikely in Chelsea, because you’ve got all sorts of other influences there. There are all the French and Germans who want houses there – and they’re getting places 20%-25% cheaper simply because of the strong euro. But I can see prices falling 25%. And in Fulham, dropping 30% or so.

James: I wouldn’t be too sure about those foreigners. They don’t want to own depreciating assets anymore than the rest of us and, of course, they don’t have to live here. Suddenly, they’ll see houses for what they are: breezeblock rectangles that cost more than an Aston Martin by square footage. Last time round, central London prices fell just as much, if not more, than average national prices because they got bid up high in the first place. Rich people aren’t stupid and Chelsea isn’t safe. Nowhere is.

Seema: There is an idea that foreigners somehow don’t have as much information about property markets here as the rest of us. But they can see the economy is slowing down – and it seems inevitable that the slowdown will get worse over the next six to nine months. So that’s got to deter a lot of foreigners from moving into London – it doesn’t matter where, Chelsea, Fulham, Angel, anywhere.

Henry: And by the way, what about Scotland? The Scots seem to think they have an insulated market that’s going to carry on ad infinitum. But there’s no reason for that to be the case. Everyone thinks their market is special. Not so.

Seema: Scotland is one of the least overvalued regions in the country, but that doesn’t make it immune. On a valuation basis, Scotland looks less bad, but they have to go to the same mortgage lenders – so they can’t be immune from the credit crunch. Overall, our current forecast is that house prices across the country will be 20% lower at the end of next year than they were at the end of 2007. But the data of the last few weeks has shown that the downside risk to that forecast is growing fast. And we think house prices could continue to fall into 2010, and potentially longer.

I’d also agree with James that the crunch was a catalyst, but that’s all. New buyer prices were already falling in January last year, so there was already a fundamental weakening of demand. Now the crunch is a major factor. Some people may be tempted to jump in, but they can’t get a mortgage, whereas other would-be buyers are just running scared from a falling market.

James: Well, the great irony is that they’re going to run more scared the more it falls.

Seema: Exactly, it’s a self-fulfiling prophecy.

Merryn: Can I ask you all how far you expect prices to fall and how long you think it will take to hit the bottom?

James: I’m pretty sure I’m right in saying that we have never had a property correction in any market that took less than five years. The last one took seven. So a minimum of five years. And I reckon it won’t be long before you can get it at 50% off at auction, or at a foreclosure.

Henry: 30%. 2012 before we hit bottom.

Ed: 25%, I think, and two years.

Seema: By the end of next year, 20%-25%, but falls for at least another year.

Merryn: John, are you going to go with 50%?

John: No, 25% nominal over the next three years. Obviously in real terms it could be a bit more, but it’s more than I’ve ever said before.