Everything is bigger in America. When Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September it reported $639bn in assets and debts of $613bn – making it by a long way the biggest corporate failure in history. Overall, eight of the ten largest collapses on record have been US firms. (The other two were Japanese financials – Hokkaido Takushoku and Yamaichi Securities – during the 1997 crisis.)

But Lehman was exceptional, even for the US. Before September, America’s biggest investment banking collapse was junk bond pioneer Drexel Burnham Lambert in 1990. It headed to its grave with $3.6bn in assets and $3bn in liabilities on its balance sheet – a mere $5.8bn and $4.9bn in today’s money.

Those numbers tell you how much financial firms have ballooned over the last twenty years. Partly, that’s the result of merger stacked upon merger. But it also reflects a huge bubble in debt – a bubble that is finally bursting with enormous consequences for investors…

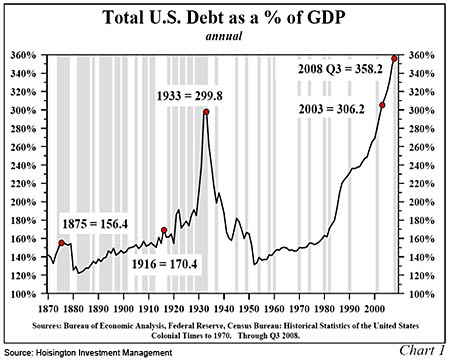

America’s debt is at all-time highs

Take a look at the chart below. It shows all US debt – personal, corporate, financial sector and government – as a percentage of GDP. As you can see, leverage in the economy today exceeds the depths of the Great Depression, when debt/GDP spiked as GDP collapsed 30%.

Charts like this have been appearing all over the place recently, because it paints a pretty scary picture. But while it’s useful, it overstates things a little and hides some important trends. On the chart below, I’ve focused on private sector debt only and split it into three categories (unfortunately, this series only goes back to 1975 in the Fed’s online database).

As you can see, there’s clearly been a big expansion in consumer debt (the blue block) since the late eighties – it’s roughly doubled as a percentage of GDP.

That’s set to change. Households will try to pay down debt, at least to the point where it was when the housing bubble kicked off around 2000. Savings rates have already begun to rise sharply, as you can see in the chart below. The American consumer will no longer be driving the global economy. That has huge implications for Asian economies that are built around exports, as I’ve discussed before.

The biggest bubble has been in financial debt

Overall, the corporate sector looks much healthier; debt has barely increased for non-financial corporates, despite the debt-driven buyout boom. It’s likely that American corporates will fall into two groups over the next few years: half (the prudent ones) will be okay and half (the Leveraged Buy-Out (LBO) victims) are in very serious trouble.

But the financial sector is another matter – debt here has soared in the last ten years. Some of this debt forms links in the chain that leads to lending to households and businesses. The lend-and-securitise (in other words, making loans and selling them to someone else) model that we’ve used in the last few years has meant that issuing $1bn in new mortgages might take three, five, ten times as much debt issuance along the chain.

Ultimately we can do without much of this and revert to a simpler lend-and-hold model. But that will take time, during which credit to households and businesses will be tighter. Much of the reckless lending will not come back at all.

Of course, this will be devastating for financial sector profits, which have risen to all-time highs, as you can see on the chart below. But there will be few tears shed for bankers.

Cheap debt creates asset bubbles

But the huge expansion in financial debt is also due to the growth in leverage at investors such as investment banks, private equity and hedge funds. This debt is utterly unproductive: its sole contribution has been in inflating financial asset prices over the last 15 years or so. Take a look at the trend in the dividend yield on the S&P 500.

Why did the yield spend 15-20 years at new all-time lows? Some argue it’s because of falling inflation. That’s probably part of the story. But it’s unlikely to be the whole one. In the long-term equity dividends should be able to pass on inflation fully. Equities are (long-term) real assets, so you shouldn’t expect share prices to respond to falling inflation as fully as nominal assets such as bonds.

Instead, it’s likely that excess liquidity in search of investments – the consequence of the huge increase in financial debt – pushed up equity prices and depressed yields.

Income matters – and so does where you start

Why does this matter? Last week (How to invest for inflation or deflation), I showed you a chart showing how income has been the key driver of equity returns over the last century. The chart below expands on this, showing how the starting point – initial dividend yield – is actually more important than dividend growth or rising price/earnings multiples over the medium term (five years).

Indeed, for total real returns since the 1970s, initial dividends have been the dominant factor across five major markets, as you can see below.

Even well into this bear market, many assets are still not cheap. If dividends drive returns as they have before, the yield on US equities is only just approaching the point where they are likely to offer any kind of reasonable return in the long term.

And deleveraging is still going on. Right now, it’s likely that a lot of leveraged money holds US assets. That’s because the first things people dump in a panic are riskier assets, such as emerging markets. This is why the MSCI Asia ex-Japan index is trading not far above the trough valuations it hit during dark days such as the Asian crisis of 1997-1998. Meanwhile, US equities are far away from typical bear market troughs.

In short, the debt-driven overvaluation has still not been corrected in many of the most overpriced assets. Investors in these can either expect further sell-offs as financial debt shrinks or mediocre long-term returns because of the low yields they’re starting from.

Asia is looking to the future

Since Asia is generally not overleveraged in any respect, the debt crisis is less of a long-term issue there. As we know, the region is still geared to the Western consumer. The recession will be brutal and the change that must be made will be hard. But at risk of being overly optimistic, some of the news that’s come out of the region is far more encouraging than the talk in the West.

The British government is more focused on trying to get Fred Goodwin to cough up his pension than fixing the disastrous Lloyds/HBOS merger. America is floundering in search of a way to bail out AIG, Citigroup and Bank of America without using the dread word ‘nationalisation’. Europe still refuses to acknowledge the likelihood that the stronger EU states will have to bail out weaker peers.

Asia on the other hand, seems to be thinking ahead. Taiwan is talking of plans to develop biotech, green energy and medical services sectors. Hong Kong’s latest budget outlines its goal of becoming a technology centre. Malaysia is promoting its Islamic finance expertise.

China has been quietly adding new economy-boosting schemes on top of the stimulus package announced last year and more are likely to come – including, some think, a much bigger investment programme. It’s also continuing to pursue free-trade agreements with some of its neighbours.

The 10-member Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean) has agreed another round of free-trade deals involving the group, Australia and New Zealand. And Asean, China, Japan and South Korea have also agreed to set up a long-mooted foreign exchange pool to support any members who find their currencies under threat in another round of the crisis.

Much of this is just words so far. It’s far from certain that everything will be done. And none of it means a quick end to the global recession. But the message is that Asia is still looking to the future while the West is struggling with the past.

In other news this week…

| Market | Close | 5-day change |

|---|---|---|

| China (CSI 300) | 2,140 | -8.7% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 12,812 | +0.9% |

| India (Sensex) | 8,892 | +0.6% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 1,285 | -0.9% |

| Japan (Topix) | 757 | +2.3% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 891 | +0.1% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 1,872 | -0.5% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 1,595 | 0% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,063 | -0.3% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 4,557 | +2.7% |

| Thailand (SET) | 432 | -0.7% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 246 | -2.7% |

| MSCI Asia | 69 | -1.0% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 254 | -0.6% |

Vietnam opened its first oil refinery after years of delays to the project. The 140,000 barrels/day Dung Quat plant should meet one-third of the country’s fuel demand next year. A second 200,000 b/d refinery, Nghi Son, began construction last year and is scheduled for completion in 2013, while a third 240,000 b/d project, Long Son, and an expansion to Dung Quat are under discussion.

India reported weaker-than-expected growth for the latest quarter. GDP grew at 5.3% y/y, with capital investment – the key driver of the country’s recent performance – growing just 5.3% y/y compared with 15.1% y/y the previous quarter. Private consumption also weakened, partly offset by a rise in government spending, which is unlikely to be sustainable. In Japan, industrial production fell by a record 10% m/m in January, with manufacturers expecting a similar fall for February.

In corporate news, Baosteel, China’s biggest steelmaker, is to take control of Ningbo Iron & Steel, a much smaller competitor, as part of a government plan to consolidate the industry. China’s fragmented steel industry is suffering from excess capacity and too many marginal producers as global demand for steel slumps. And ANZ, Australia’s third-largest bank, is preparing a bid for the Asian assets of RBS, according to reports in the South China Morning Post. Standard Chartered is also said to be interested in bidding.

This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world’s fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here.