Funds are getting so big they can’t stoop to pick up smaller firms. That’s great for nimbler players such as Nick Greenwood, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

If you are a client of a wealth-management firm it might feel to you as though nothing much has changed with them in 30 years. Still a bit too expensive. Still mildly confusing. Still prone to sending you too many bits of paper with not quite the right bits of information on them. All that.

But there has been one major change: consolidation. Wealth-management firms used to be pretty small. Now, after a decade or so of merger and takeover, they are pretty big. They’ve also mostly changed the way your manager is allowed to run your money. Even 15 years ago he (usually he!) would have made you a bespoke portfolio – a range of stocks and funds chosen by him just for you. Not any more. All this individual thinking is now considered to be too expensive. So most client portfolios are now centrally structured. There is an approved list of investments from which all client portfolios (often identical at any given risk level) must be created.

This has the virtue of simplicity. But it comes with a potentially return-limiting side effect: to make it on to the approved list an investment has to be big enough for the firm to be able to buy enough of it to put some in every client portfolio – and to be able to sell it easily should it need to. The result? Smaller companies increasingly don’t make the cut.

Finding value in missed opportunities

With this in mind I went to see Nick Greenwood of Miton Global Opportunities, a small fund that invests only in other closed-end funds. There are around 425 closed-end funds listed in London; 315 of them have a market capitalisation of less than £400m – which is about as small as the larger wealth managers can go (a number that keeps rising – it was £150m only a decade ago). The result? Lots of the funds have been “orphaned” – brokers, institutional investors and wealth managers ignore them; they are fairly illiquid, and they often end up trading on unjustifiable discounts to their asset values.

This, says Greenwood, is good: it is an opportunity for “diligent and specialist investors” (like him) to pick up the value others are leaving on the table, particularly now that so many trusts are focused on the kind of unlisted investments (property, forestry, P2P lending and the like) that many find hard to value. Right. Where’s the value now?

We start with Berlin property. Many of us at MoneyWeek got burned getting into this too early via a fund that was too highly leveraged (if you have too much debt you can be right and still lose all your money). Greenwood has not made this mistake.

“SINCE BUYING INTO TALIESIN PROPERTY FUND, THE PRICE HAS RISEN 470%. SURELY THAT SHOULD BE ENOUGH, I SAY, WITH ONLY A HINT OF BITTERNESS…”

The fund has been holding Taliesin Property Fund since February 2011. Since then the price has risen 470%. Surely that should be enough, I say, with only a hint of bitterness. Everyone knows the Berlin story now. Time to sell? No. Property prices are still low and Berlin has a good chance of becoming a “world city”, given its location and attractions to the tech sector and international investors, “particularly with all the uncertainty over Brexit”. Berlin has already moved from being an “urban wasteland to becoming a major capital city” in less than a generation.

There is risk in the fact that Berlin has a left-wing government and that 85% of residents (and hence voters) are still tenants – this means it is hard to buy up blocks and get the permissions to sell them privately. But Taliesin doesn’t have this problem: it has permissions in place on 56 of its 63 buildings in Berlin. These buildings are valued at €3,000 per sq m, but this, says Greenwood, does not reflect their real value – it’s probably more like €5,000-€6,000. Note that even on the higher valuations, Berlin is half the price of Munich.

Where else looks good? Private equity. Lots of the big funds have huge volumes of cash they need to invest if they want to max out their fees. That makes it a sellers’ market – and investment trusts have assets to sell. Look to Better Capital 2009, EPE Special Opportunities and Dunedin Enterprise, all of which are effectively in wind down – selling assets to greater fools and returning capital as they go.

India: wait for the breather then buy in

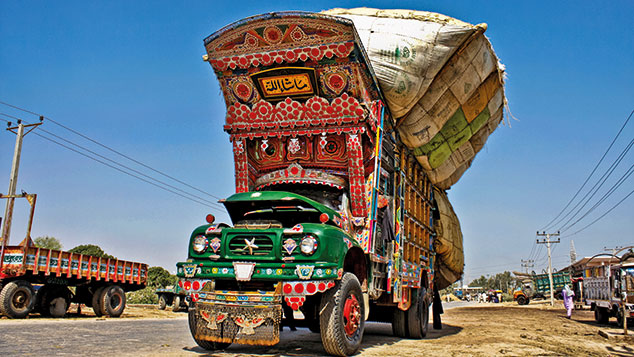

Otherwise, Greenwood’s top holding is the India Capital Growth Fund. India has potential. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is trying to make “what already exists work better”. His recently introduced national goods and services tax, for example, means you can now drive a lorry from city to city without adding in an extra day for stopping to pay cash bribes. “Keep taking out the bureaucracy and the ability to offer a bung” and eventually you will get somewhere. The man in the street sees this, says Greenwood – so they will put up with short-term disruption for long-term gain.

All the changes designed to promote the formal economy at the expense of the informal will give a “structural advantage to listed companies”. And India is one of the few emerging markets that offers real depth: it’s been there since 1895, so if you want someone making anything from “bicycles to skin-whitening cream” you can genuinely stock pick. Both of these things mean that a good manager has a better chance of outperforming in India than in most other emerging markets. That said, Greenwood wouldn’t necessarily urge anyone to dive in for the short term: the market’s been a fabulous performer this year and, with price/earning ratios averaging 18-19 times, it is now “desperately in need of a breather”. He has “top sliced” his holding with this in mind (while reminding me that attempting to time the market too closely is a fool’s game). You should wait for the breather and then have a look at it.

A fun rummage around

In the meantime, Greenwood has lots of other interesting holdings. There’s Aurora Investment Trust, one of the few funds in Greenwood’s fund not trading on a huge discount. Why does he own it? He is “backing the manager” as a stock picker. We like that one too (see my interview with its manager, Gary Channon). My eye is also caught by Artemis Alpha, which is effectively a vehicle for three of the fund managers at Artemis (they own 20% between them). It is trading on a 20% discount, having been hampered by a few bad unquoted investments and a perception that it is overexposed to the oil and gas sector (it isn’t particularly). But as the three managers own a big chunk of the fund themselves, they are unlikely to let it languish indefinitely. If the current team can’t sort it out, Artemis will surely find an “internal solution”, says Greenwood. Hang on for that.

“THERE’S LOTS OF FUN TO BE HAD LOOKING THROUGH GREENWOOD’S HOLDINGS FOR THE GEMS YOU MIGHT LIKE IN YOUR OWN PORTFOLIO”

Finally, we talk about Phaunos Timber, a trust I suspect a lot of MoneyWeek readers will hold (it once looked as if it were a fabulous way into timber). This should have been a great turnaround situation, says Greenwood. After some troubles it got a new chairman with both FTSE 250 and forestry experience. He hired in people “who really knew forestry” and got rid of all the rubbish in the portfolio. But unfortunately the board didn’t do the marketing they needed to do; the trust remained on a 30% discount; it was attacked by activist investors; ended up with another board of financial engineers rather than industry experts; and has now had to become a forced seller of its minority assets (where it owns less than 50%). That cuts both its net asset value and the fund’s long-term yield. Not good. So it’s a sell? It’s certainly not a buy. But anyone holding might as well sit and wait as the assets are sold down. You’ll get the share price back at least.

There’s lots of fun to be had looking through Greenwood’s holdings for the gems you might like in your own portfolio. Or you can get access to the lot by just buying his fund. The ongoing charges end up being high, despite a low management fee, at 1.4%, but long-term holders will have found comfort: the fund has returned them 88% over the last five years.

Fact file: Nick Greenwood

Nick Greenwood began his career in private-client stockbroking in the late 1970s. He was a founder member of Christows stockbroking operation in 1991. He joined the Christows Investment Trust in 1995, then iimia in July 2002. He became chief investment officer following iimia’s merger with Exeter Fund Managers in August 2005, then joined Miton Group following its merger with Exeter Fund Managers in November 2007.

He now manages both Miton Global Opportunities (formerly Miton Worldwide Growth Investment Trust and the trust mostly discussed above) and the CF Miton Worldwide Opportunities Fund. He is hoping for no more mergers. Figures from Trustnet suggest that Greenwood has outperformed his peers over ten, seven, five, three and two years. Over five years his investors have seen a cumulative return of just over 80%.