I saw a chart the other day, which rather caught my eye.

I think there may be a considerable opportunity here.

In today’s Money Morning, we consider zinc…

A very dull metal indeed

It’s said that a good investment should be boring. Dull old zinc certainly ticks that box.

It doesn’t have the glamour of gold, silver or diamonds. It doesn’t have the excitement of some tech start-up. It doesn’t have the comfort of some dividend-paying large cap.

It’s just zinc.

Unlike lithium or uranium, zinc doesn’t even have the potential to solve some looming global problem.

Its main use (over 50%) is in galvanizing. Zinc is highly reactive – a quick coat of zinc on your iron or steel will attract all the oxidization and so protect the metal beneath. Thus zinc finds considerable use in the construction industry. The frames of buildings, bridges, roofs, staircases, beams and piping all contain zinc.

It’s also used in alloys (brass and bronze) and in compounds, with a range of applications. Many batteries contain zinc – from the AA batteries in my mouse to the silver-zinc batteries used in aerospace to zinc-bromine batteries used in energy storage. You’ll find zinc in keys, coins, zips and, of course, dustbins of the old school, now hipster variety.

Zinc is the fourth-most widely-used metal in the world, after iron, copper and aluminium. Per year, it’s about a $38bn market. To put number that in loose perspective, it’s perhaps double the size of the silver market and maybe a fifth of the size of copper.

According the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (IZLSG), 2017 usage will come in at 14,302 tonnes. It’s no surprise that the biggest consumers of zinc is China, who account for almost half annual zinc demand. China is also world’s largest producer, contributing between 35 and 40% of global supply. Overall, it is a net importer.

The trend in recent years has been for zinc mines to shut down. In China many mines (26 in 2015-16) were shut down for environmental reasons. Elsewhere the reason is depletion.

Notable recent closures include Lisheen in Ireland, Century in Australia – which between them accounted for around 5% of annual global supply – and Glencore Xstrata’s Perseverance and Brunswick mines.

The largest zinc mine in the world is Hindustan Zinc’s Rampura Agucha operation in India. Production there fell sharply in 2016 as an underground section of the mine was developed. This has now been completed and production is expected to recover strongly this year.

Nevertheless, the global zinc market remains in deficit – ie more is being consumed than produced. According to IZLSG, in the first four months of 2017, the zinc market was in a deficit of 112,000 tonnes versus a deficit of 20,000 tonnes in the same period last year.

As a rule of thumb, for supplies of metal to be sustainable, miners need to find about twice as much metal as is currently being mined. So for every 1,000 tonnes you mine, 2,000 tonnes need to be discovered (not all metal is recoverable), otherwise there will be shortages.

Following the post-2011 mining recession, by 2013, the ratio for zinc had fallen to 0.7. The shortages were eventually realised in the price, and in 2016, zinc turned out to be one of the best-performing commodities, rising by around 60%.

Forget Dr Copper – pay attention to Dr Zinc

So far in 2017 zinc has range-traded. The first six months saw a slow down, perhaps brought on by falling Asian steel demand. But things have turned in the last month or two. At today’s price of around $2,735 per tonne, zinc up about 8% on the year.

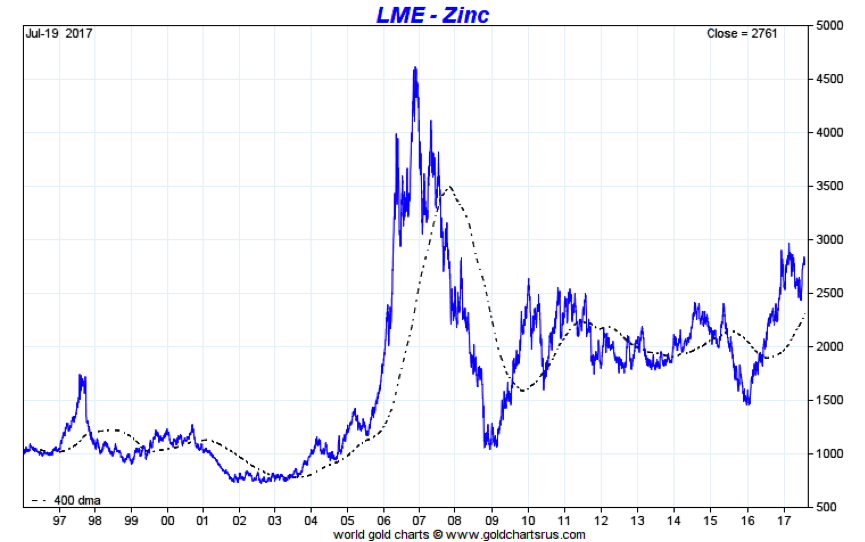

Here, from the doldrums of the 1990s to the bonanza of the 2000s, is the zinc price over the last 20 years.

Copper is often credited as having a PhD in economics because of its predictive powers – hence Dr Copper. But to my mind, zinc is rather better at the job.

Notice how it peaked in late 2006, anticipating the great recession well before copper, which was making new highs as late as summer 2008, even as the financial world was falling apart.

So to the chart that caught my eye – which I saw posted by blogger and mining analyst, Otto Rock, in his IKN newsletter. It shows the stockpiles of zinc at the London Metals Exchange (LME).

LME zinc stocks, currently near 270,000 tonnes, are down by 37% this year, and by more than 75% from their 2013 highs. And they keep falling. They have only been this low twice in the last 20 years. Once in 2001 and once in 2008, during the financial crisis. Bull markets followed both times.

According to metals analyst Kaynat Chainwala, cancelled warrants (stocks earmarked for delivery) on the LME stand at 70%, indicating tightness in supplies of the metal. Shanghai stocks are similarly tight, down by 50% near 78,000 tonnes.

Much of zinc demand will be determined by steel demand, but the stage is being set for zinc to enjoy a pleasant second half of 2017 and perhaps beyond into 2018.

The simplest way to invest in zinc is to buy one of the zinc exchange-traded funds (ETF Securities offers a London-listed one under the convenient ticker ZINC) or to buy it via a spreadbet. All the usual risk warnings apply (particularly to the spreadbetting).

There are also the large miners – BHP Billiton (LSE: BLT), the world’s largest producer, Anglo-American (LSE: AAL), Vedanta (LSE: VED) and KAZ Minerals (LSE: KAZ), although none are pure plays, as they all produce other metals.

At the speculative end of the market are the tiny-cap zinc exploration and development plays. This is where you’ll find the purest, most leveraged exposure.

You’ll have to do your own research on these (although if I can twist John’s arm, I may write something more detailed on these stocks for MoneyWeek magazine – subscribe now if you haven’t already). But there are plenty of possibilities on both London’s Aim market and on the TSX Venture Exchange in Canada (although for what it’s worth I prefer to focus on the Canadian market).