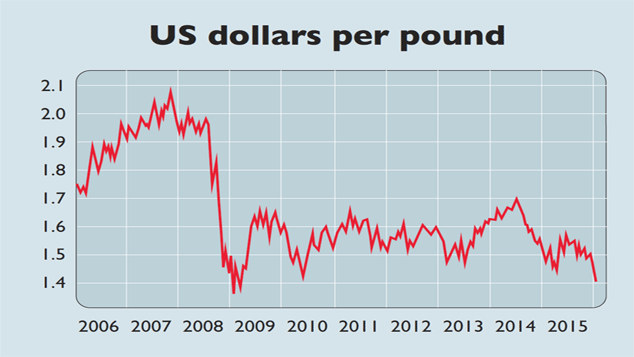

The pound “is in the doghouse, no mistake”, as BNY Mellon’s currency strategists put it. It has fallen to a seven-year low against the dollar. Over the last eight weeks it has plunged by almost a tenth against the euro, its worst losing streak since the single currency’s inception – a striking statistic when you consider that the European Central Bank is doing its best to weaken the euro by printing €60bn a month. In trade-weighted terms – compared to a basket of trading partners’ currencies – it has reached a 12-month low. Analysts’ forecasts are chasing the pound downwards.

So what’s gone wrong? The key issue, says BNY Mellon’s Neil Mellor, is that “the pound has been a victim of unrequited expectations about monetary policy”.Last year, investors thought it might not be too long before the Bank of England followed the Federal Reserve in America and raised interest rates for the first time since the crisis. Hawkish rhetoric by the Bank’s governor, Mark Carney, reinforced these expectations, and the currency ticked up: higher interest rates increase the return on sterling-denominated assets.

As the Bank was one of the few contemplating raising rates, the pound was especially vulnerable to a change in the interest-rate outlook, says Tommy Stubbington in The Wall Street Journal. This duly happened when the Bank appeared to get cold feet in November, saying the shakier global economy made rate rises less urgent. Now domestic data has weakened too, while the plunging oil price will delay the return of significant inflation. As a result, “the market has turned extraordinarily dovish”, says Sam Lynton-Brown of BNP Paribas. Investors only expect a rate rise in early 2017 – an impression Carney did nothing to dispel with a dovish speech this week.

With global uncertainty mounting, investors may also be starting to fret about the ramifications of a vote by Britain on whether or not to leave the EU. BT chairman Michael Rake told Bloomberg last week that the debate has already cost Britain some foreign investment. This is awkward because Britain has a relatively large external deficit; it’s expected to total around 4% of GDP in 2015. A deficit with the rest of the world implies a weaker currency, which should help correct it, but this is especially likely if the international capital flows that plug the deficit are endangered by political uncertainty.