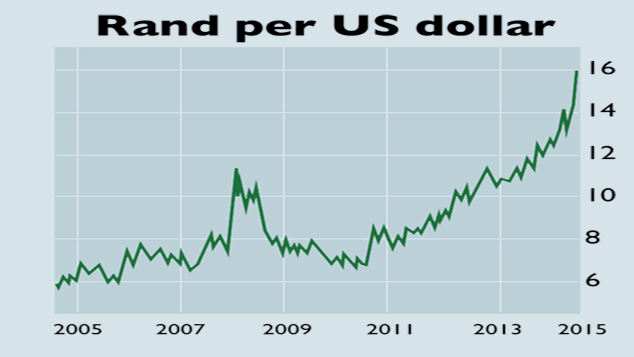

“This is a mess-up of epic proportions,” economist Dawie Roodt told Fin24.com. “It is like we’re living in Alice in Wonderland.” Last week, the South African president, Jacob Zuma, fired his respected finance minister Nhlanhla Nene, sending the rand crashing to a record low against the dollar. Meanwhile, ratings agency Fitch downgraded South African government debt to one notch above “junk”, sending bond yields to their highest levels since the global crisis six years ago. Early this week, however, the market and media furore prompted a major U-turn. The obscure backbencher who had followed Nene was in turn replaced by Pravin Gordhan, Nene’s predecessor, who also has a solid reputation with investors.

What’s going on?

Nene had consistently tried to force the government to keep a lid on its spending and “had stood up to powerful allies of the president”, such as the chairman of the ailing state airline South African Airways, says The Economist. Given the ratings downgrade and the fast-rising public debt pile – national debt has jumped from 26% to 45% of South African GDP since 2009 – investors were worried that further careless spending could lead to a fall into junk territory, ever higher interest payments and, eventually, a bail out from the International Monetary Fund.

The debt picture is alarming because South Africa just isn’t growing fast enough to work it off. Annual growth is likely to be 1% this year and has been stuck around that level since 2012. This is partly due to external factors, says Songezo Zibi on BDLive.co.za. The slowdown in China, South Africa’s biggest trading partner, has hit demand for commodity exports, and Europe, its number two trading partner, is stagnating. The current-account deficit has deteriorated, weakening the rand, which in turn has pushed up inflation and prevented the central bank from cutting interest rates.

But there are plenty of home-grown problems too. Underinvestment by the state-owned electricity company has caused widespread, recurring power outages. Red tape, especially for small firms, poor state education and rising cronyism and corruption are common complaints from businesses. There has been “a generalised trend towards institutional decay” in the past few years, says the Financial Times. Assuming that solid pre-crisis growth would endure, the government kept spending – the state wage bill has doubled since 2009 due to a civil servant hiring spree and repeated strikes – and now that growth has evaporated, the deficit is deeply entrenched and debt has soared.

Will Gordhan’s reappointment allay market jitters?

For now – but the damage is done. “You’re in a country where you can expect such moves – that’s never reassuring,” Aberdeen Asset Management’s Viktor Szabo told The Wall Street Journal. With frustration at stubborn unemployment and slow growth spreading, investors are right to fear that the government will be tempted to indulge in populism, ultimately making the debt problem worse. And ongoing internal power struggles in the ruling African National Congress mean it’s far from clear that Zuma’s replacement will be a steadier, more market-orientated figure. Don’t expect a rand bull market anytime soon.