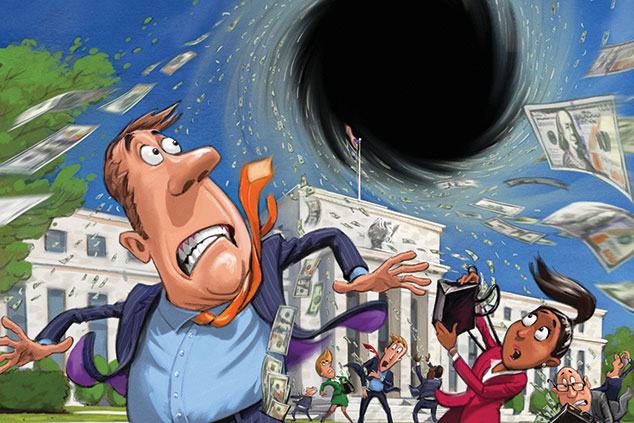

Quantitative easing has inflated property, share and bond markets alike. The end of this great monetary experiment threatens to blow black holes in balance sheets everywhere, warns Jonathan Compton.

For sleepless investors out there, notable cures for insomnia include a bedtime flick through the minutes of America’s Federal Open Market Committee. Alternatively, there’s always the bestselling book A Brief History of Time, by theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking – allegedly fewer than a quarter of the ten million buyers of this actually read it all the way to the end. Yet vigilant investors might want to have a crack at staying awake through both – because right now a black hole is opening up in the global financial system whose gravitational effects are sure to suck money from equities, house prices and other asset markets.

A little more than ten years ago the global financial system came perilously close to collapse after years of incompetence, stupidity and greed by banks, governments and the public. In desperation, the Federal Reserve (America’s central bank) found a solution that had been used on a limited scale in previous downturns, and aggressively in Japan between 2001 and 2006 with mixed results. This solution was quantitative easing, or QE. Despite vigorous opposition from politicians on both left and right, as well as most economists, it was introduced on a giant scale, then expanded further. Similar measures were adopted by the Bank of England (BoE) and later by the European Central Bank (ECB), while it was also reintroduced in Japan. The result was that financial Armageddon was at least postponed.

Printing money to save the world

The mechanics of QE seem abstruse, but in essence are simple. The banks and many other financial institutions were about to go bust, with bad debts up to their nostrils and no reserves. Thus they were being forced to sell anything not nailed down and to call in loans to customers or each other – a classic financial death spiral. QE allowed the central banks to create electronic money. At first this was used to buy government bonds at above market prices from financial institutions, then later to buy corporate bonds and other assets. In extreme cases such as UK high-street bank RBS, or Bank of America in the US, money was pumped in via loans or equity to ensure they could remain in business.

The ECB was even more extreme – restrained from acting more transparently by the tricky politics of the eurozone, it went so far as to guarantee a risk-free profit for eurozone banks. It lent them money at almost zero interest to buy eurozone bonds with a much higher yield from the ECB. As a result, interest rates were forced down to record low levels. This means that those who were overborrowed could continue to pay their debts, while financial institutions eventually stopped calling in loans and began to lend more (although the banking systems in the US, and to a lesser extent the UK, remain healthier than that of the eurozone), which helped to encourage investment and create employment, leading to economic growth and higher tax receipts.

The forecasters were once again wrong-footed. Economic dogma said that massive money printing must cause inflation to soar. The reverse happened – indeed, the global economy has only just started to edge away from the deflationary abyss. Another accepted fact was that confidence would collapse (instead, it rose) and that economic growth would accelerate (as inflation took off). This latter is the most interesting – across countries that engaged in QE, growth did indeed sputter slightly higher for most of the ensuing decade, but only at a great cost. For every dollar or equivalent currency borrowed, there was only about 40 cents of growth. Borrowing 100 to get back 40 is bad maths (and unsustainable to boot).

The silence of the presses

In all, it was an impressive three-card trick. In practice these central banks took truckloads of bad debts out of the system and onto their own books; hence the Bank of England’s “balance sheet” (I’ve used inverted commas here because it doesn’t add up in reality) has increased in size by almost fivefold since 2008 to £490bn, and that of the Fed from $825bn to $4.4trn.

All this changes this year. Central banks and their political masters have decided this unique experiment must stop. As a result, the Fed, the ECB and the BoE have announced the end of their buying programmes. In the case of the Fed – which ended QE a while ago (see box on the left) – it will also start to sell off its vast bond portfolio. There are several reasons behind this attempt to return to “normality”. One is a fear that overall debt-to-GDP ratios are still recklessly high: 108% in America and 225% in Japan, for example.

Another reason is that budget deficits (annual government overspending) remain stubbornly large in many countries and the addiction to all-but free money can only result in economic cold turkey

later. Furthermore, record low interest rates have caused dangerous bubbles in house prices and equity markets. Worse still, perhaps, is the significant deterioration in the “quality” of corporate borrowing that we’ve also seen. More than 40% of the world’s corporate bonds are now rated BBB (only a smidgeon above the grade at which they become aptly named junk bonds). That’s three times the proportion seen just five years ago. Elsewhere there has been an explosion in the level of corporate debt in emerging markets, often mismatched – ie, borrowing in a foreign currency but funded locally. This formula usually ends in tears (as Turkey and Argentina have just rediscovered).

A major political problem is that there is clear evidence that an unintended consequence of QE has been to make the wealthier considerably better off (by boosting asset prices – after all, it’s the wealthy who own the most assets), while doing little for lower-income earners. That’s ballot-box suicide, and one reason behind the numerous political “surprises” we’ve seen in recent years. But perhaps the greatest concern for central banks is that continuous QE and ultra-low interest rates mean there is no cushion against the next cyclical downturn.

A brief history of quantitative easing

Global central banks have expanded their balance sheets dramatically via quantitative easing (QE) in recent years, writes John Stepek. But as Jonathan points out above, it’s now coming to an end. So far, QE withdrawal has come in three phases. There’s “tapering”, where the central bank still buys assets each month, but at a slower rate. So its balance sheet is still expanding, but at an ever-slower rate. For example, in December 2013 the US began to taper, cutting bond purchases from $85bn a month to $75bn.

Then there’s the “maintenance” phase, where the central bank buys no new bonds, but still reinvests the proceeds of those that mature. So its balance sheet stays roughly the same size. The Fed did this between October 2014 and October 2017.

Then we move on to the quantitative tightening (QT) phase. This is where the central bank actively starts to shrink its balance sheet. The Fed is now at this stage. Since October last year it has been allowing bonds to mature without reinvesting the proceeds. As a result, the Fed’s balance sheet has fallen from nearly $4.5trn a year ago to just above $4.3trn now.

Meanwhile, the Fed has also been raising interest rates. We saw an initial hike from 0% in December 2015 to 0.25%. Now the Federal funds rate is up at 2%. So where are the rest of the world’s central banks in this process? The Bank of England is further behind the Fed – the UK central bank bought £375bn of gilts via QE between 2009 and October 2012, then restarted QE in the post-Brexit panic, expanding its balance sheet by another £60bn. The key interest rate is at its post-crisis level of 0.5%, having been cut briefly to 0.25% after the vote to leave the EU.

The European Central Bank only started QE in March 2015. It plans to taper its purchases later this year, dropping from €30bn a month in September to a complete end by January 2019. The key interest rate sits at 0%.

The Bank of Japan has maintained its own QE – a promise to buy as many bonds as necessary to keep the ten-year yield at 0% – and shows little sign of ending it. This backs up Jonathan’s suggestion that Japan may be a good “macro” bet during QT.

Sucking money from the system

The end of QE leaves a chasm-wide funding gap (ie, the amount of money the government needs to borrow to bridge the hole between what it spends and what it raises in taxes). Over the past two years central banks have absorbed more than all the government bonds issued by the world’s ten richest countries. Now they will only be buying around 40% of those. So who is going to fund the difference? Usually it would come from a combination of domestic savings and countries with excess foreign-exchange reserves.

Yet in most advanced nations savings rates are close to, or at, 20-year lows, while institutional cash levels are also slim, reflecting dangerously bullish expectations that equity and bond prices will rise forever. The two Asian nations that have historically funded a large part of Western lifestyles are less able to do so. China’s reserves are down by nearly a trillion dollars from the 2014 peak; Japan’s are close to record highs but its budget deficit remains excessive.

The key determinant to what happens is, as usual, America. The new Fed chairman, Jerome Powell, and Congress are not just ending QE, but are also keen to sell off their holdings of US Treasury bills, even while the supply of new bills to fund the government continues to rise. Long ago America ran out of sufficient domestic savings, so had to entice foreigners to fund its deficits and it will do so again. But to attract foreign buyers, interest rates need to be higher than those offered on other major currencies, which indeed they are. Combined with tighter monetary conditions the dollar should strengthen, making funding America’s debt even more attractive to overseas investors. But other countries also need to fund their government expenditure and deficits. They in turn must react by raising domestic rates higher than would otherwise be necessary.

Expect lower returns

Monetary policy generally attracts little attention from the wider public and many of its consequences are unforeseeable. Yet we are about to witness the end of the greatest monetary experiment ever devised, at a time when the level of total world debt-to-GDP is the highest in history. QE ended one crisis, but also turbocharged stockmarkets and enabled firms globally – and in emerging markets especially – to bloat out on cheap, often mismatched debt.

Meanwhile many of us have relished ever-higher property and asset prices. Only an extreme optimist would believe that, given its positive impact on the way up, a reversal of QE will leave markets entirely unscathed. The only question is whether the black hole causes a mild downturn or full-blown recession. The “good” news is that the correlation between growth and index returns is weak, so slower growth is not necessarily a cause for alarm. But stockmarket history does provide a playbook for the probable outcomes, all of which suggest that future returns will be much lower than those we’ve enjoyed recently. We look at how best to insulate your portfolio below.

Insulate your portfolio as QE ends

Voodoo is slightly more rational than efforts to forecast exchange rates, but that said, I am convinced that the dollar will continue to strengthen. When this happens, along with rising US interest rates and tighter money, there is one sure-fire consequence: the wheels rapidly come off emerging markets. There are a legion of differences between individual emerging markets, of that there is no doubt – and yet, even those that have managed their finances prudently are always dragged down in these circumstances, partly because foreign investors from developed nations pull money out to invest at home. This time will be no different.

Many emerging markets learned their lessons at the government level in the 1997 crash, so the extent of overborrowing externally or foreign debt-to-GDP is much lower. (When Argentina went cap in hand again to the International Monetary Fund earlier this month, foreign debt-to-GDP was close to a 20-year low at 35% of GDP, for example.) Yet emerging-market companies have gorged on cheap foreign debt to an unprecedented extent. Many will be forced to default, creating a downward spiral and cross-country contamination, followed by some panic in Europe whose banks – unlike those in America – are once again horribly overexposed to this unpayable corporate debt.

Another historic certainty is that every time the Fed has tightened since World War II, the multiple (price/earnings ratio) on the market has contracted. Thus, for indices to continue their merry rise, profits and earnings growth has to rise dramatically. Given that corporate profits as a percentage of GDP are already close to record highs and have been rising for a decade, this is a high hurdle.

Then there is the “zombie problem”: those companies in developed markets that in normal conditions (ie, pre-QE) would have expired long ago but continue to stagger on only because rates are low. As rates rise, the zombies die. You can see examples of zombie businesses on every high street in the country.

So should investors simply sell up and head for the hills? No. Timing markets is a mug’s game and the downturn may be much less extensive than I fear. Moreover, whatever central banks may say, they too panic when markets fall fast. So any slide may be countered with interest-rate cuts and looser monetary policy – a postponement, not a cure. Also, the tight correlations between markets should loosen as monetary policy tightens (ie, they should stop moving in lockstep as “risk-on, risk-off” investing dies out.

One macro winner is likely to be Japan: a stronger dollar means a weaker yen and a higher stockmarket. Here, the Baillie Gifford Shin Nippon (LSE: BGS) investment trust’s managers continue to do an outstanding job (full disclosure: MoneyWeek editor-in-chief Merryn Somerset Webb is a non-executive director of this trust). If my view on a strong dollar is correct, then maintaining US exposure seems sensible. Here the JP Morgan US Smaller Companies (LSE: JUSC) trust has continued to deliver, with a five-year annualised return of 20%. In the UK a good place to “hide” is the Finsbury Growth & Income Trust (LSE: FGT). While I am not a big fan of income funds, as too often they sacrifice capital for income, this trust has a terrific consistency and has delivered a 300% return over the last ten years.

Utilities often perform better in less confident times and I have a hunch that there’s an opportunity in one of the least favoured – BT Group (LSE: BT.A) – which has rightly been excoriated by shareholders and the financial press for poor performance by its recently defenestrated and over-coiffured chief executive. Since the autumn of 2015 the share price has fallen from £4.70 to £2.07, but cost-cutting and rationalisation have commenced. My trigger point to buy will be when its currently unaffordable dividend is cut.

Finally, there’s the warfare giant BAE Systems (LSE: BA), which I have recommended before and continue to own. The defence sector tends to be contra-cyclical (it goes up when other stuff goes down); government defence spending in America – its largest market – is rising; and the 3.7% dividend yield is useful.