It seems like a big deal to everyone who works at Westminster or in the media, but for the purposes of this column at least we must distinguish between the political effects of the UK’s near-1,000 days of bickering and the economic effects. The former may turn out to have been significant. So far, the latter simply haven’t.

Look at UK GDP growth rates — 1.5% a year isn’t bad. It might have been better without the investment-delaying uncertainty surrounding Brexit. But against the backdrop of a global economic slowdown, it’s hard to tell — particularly as the rest of the EU is doing little better.

Ah, you will say, but there is much worse to come, obvious economic disaster lies ahead. But is it really so obvious?

A second referendum is much discussed, as is a full-on cancellation of Brexit, and both are possible — if unlikely without an interesting offer from the EU. It is worth remembering that in past second referendums, in Ireland and Denmark for example, the EU has offered a change of deal for a different result.

Barring that, you still have what look like hordes of other options – or suggestions, at least: a general election; asking for an extension; cancelling and then a bad faith re-triggering of Article 50 to buy a couple of years; sticking with the PM’s deal, but with a sunset clause defaulting to “no deal” after a year of backstop.

There are more. Agreeing to take “no deal” off the table by retracting Article 50 if there is indeed no deal by the end of March. Holding out for a last-minute concession on the backstop, on the basis that EU discipline is likely to crack close to the wire. And leaving the EU politically in March (with the long-term economic deal still to be arranged, of course).

And then there is Norway; Norway plus; a commitment to a customs union; or a return to discussing the free trade deal apparently on the table before Mrs May produced her deal.

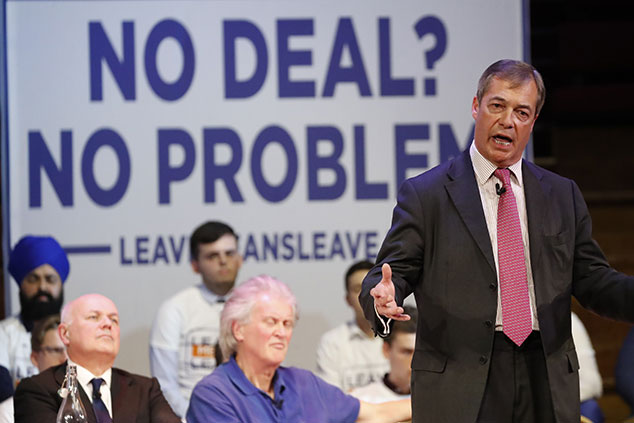

No deal is no big deal

But look at all these things and, different as they might seem to those deeply in the know, you will see that to the casual observer they come down to much the same thing: a special Brexit version of extend and pretend — or what Capital Economics calls “delay and fudge”.

Even the dreaded “no deal” itself is well on the way to becoming a version of this. It isn’t particularly likely now that May is in compromise and conversation mode. Oddschecker puts no deal at 10%; Capital Economics puts it at 25%; Franklin Templeton puts it at 30%-35%. But even if it happens, the horrible crash-out Brexit that the hysterical end of Remain like to fantasise about is increasingly unlikely.

The more we prepare, the less risky the whole thing becomes. UK companies have massively stepped up their preparations — note the regular stories of stockpiling. EU and UK governments are doing the same.

We know that mitigating action has been taken on haulage and aviation; that sector-specific agreements are being prepared; and that the UK is able to not charge tariffs on incoming goods, regardless of reciprocation, in the short term.

It is also possible, according to the WTO, says Netwealth’s Gerard Lyons, that “we could leave with ‘no deal’ and still maintain existing tariff arrangements with the EU for a long time while a free trade agreement is negotiated, provided both sides agreed — which they likely would.” How’s that for delay and fudge?

The worst a “no deal” could do at this point, says Capital Economics, is take 1% to 2% off UK GDP over a couple of years. Some are going further. “Hard Brexit?” say the analysts at Franklin Templeton. “Bring it on!”

I paraphrase their argument somewhat. “Two and a half years ago, with all the options for a negotiated Brexit on the table, a hard Brexit seemed to be the worst-case scenario,” they say. Now with proper preparation under way “markets may feel that it’s preferable to bring an end to the uncertainty and accept the short-term pain” and exporters might feel the same — assuming that in the short term, the fall in the value of the pound helps sales.

M&G’s Eric Lonergan has a similar view: “It is likely to be the worst of a set of economic scenarios, but not particularly calamitous.”

Leaving will look remarkably like remaining

Back in 2016, I wrote that in the end — in economic terms at least — leaving the EU would end up being such a massive fudge that it would be remarkably similar to staying in the EU. That looks increasingly likely — which is why, as Killik & Co put it, UK assets have been “largely unmoved” by the shenanigans of the past few days — although sterling rallied on Thursday as Jeremy Corbyn seemed to warm to a second referendum.

You can argue the politics of this forever, and many will. But the point for investors is that too much misery may now be embedded in the price of UK assets and in sterling.

Given this lack of disaster, turmoil and chaos (economically at least), what should you do?

The world is fraught with danger for investors: Germany and China are slowing, US monetary policy is tightening and most valuations feel far too high. Now is the time to look again at possibly mispriced UK opportunities.

One to consider might be something I have suggested before — the Aurora Investment Trust (LSE: ARR) run by Gary Channon (disclosure — I hold this trust myself, and so do family members). Its portfolio is jammed with the kind of domestic stocks no one terrified of a “no deal” Brexit would dare to own: think Lloyds, Redrow, Bellway and JD Wetherspoon.

Channon reckons that due in part to the over extrapolation of Brexit worries far into the future, their “intrinsic value” is a good 100% more than their current market price. If you don’t mind looking like you’re going against the flow in the short term in order to have the last laugh in the long term, he says, now is the “time to be adding money, not taking it away”. I think he’s probably right.

• This article was first published in the Financial Times