After a campaign dominated by “dire warnings” about national break up and a “return to the dark days of Franco’s authoritarianism”, Spanish voters responded with one of the highest turnouts since Spain’s return to democracy in the 1970s, says Raphael Minder in The New York Times.

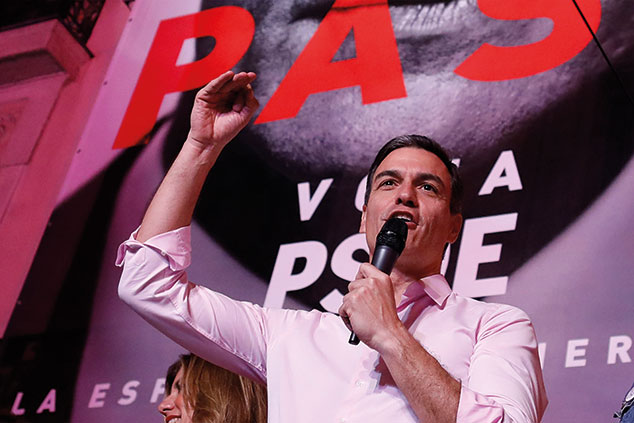

The results, a victory for incumbent prime minister Pedro Sánchez and his PSOE party, seemed “to confirm their attachment to a left-wing social agenda and to the country’s regional diversity”. At the same time, the vote gave Vox, an anti-immigration party, its first seats in parliament.

A long road ahead

Ironically, Sánchez’s victory was in large part down to the rise of Vox, which “toys with nostalgia for Franco’s dictatorship”, says Carlos Delclós in The Guardian. Vox took votes from the centre-right Popular Party – it won fewer than half the seats of the PSOE – and helped create a “widespread fear of a right-wing coalition government that would include it”. At the same time, left-wing voters deserted the anti-austerity Podemos in favour of the PSOE due to internal squabbling and controversy over a property purchase by its leaders, which was depicted in the media as a betrayal of leftist ideals.

Still, Sánchez has a long road ahead if he wants to govern, says The Times. He emerged as the winner with a “chunky 29% of the vote”, but his 123 seats are well short of the 176 seats needed to control parliament. Even forming an alliance with the left-wing Podemos and a Basque party would fall short of a majority. At the same time, an alliance with the centre-right Citizens party (Ciudadanos), which won 57 seats, is difficult because it “fundamentally disagrees” with Sánchez’s policy of “dialogue and limited co-operation with Catalonia”. Sánchez may be tempted to form a minority government.

But such a move would be a “recipe for political instability”, says the Financial Times. It would also make it difficult to deal with Spain’s “far-reaching” challenges, including its slowing economy, persistent unemployment, tight public finances and the “poisonous impasse in Catalonia following the illegal independence referendum in 2017”.

Instead, Sánchez and the leader of Ciudadanos should swallow their pride and join forces “for the sake of national stability”. Such a coalition “could deliver greater social justice while cracking open vested interests hindering growth and job creation”, while moderate concession to Catalan autonomy “might eventually deflate the independence movement”.

The horse-trading begins

The horse-trading is likely to take some time, says Carlos Cué in El País. While Ciudadanos is still ruling out a coalition, and Podemos is demanding “a place in government and a say in the make-up of the cabinet”, Sánchez and the PSOE “are in no hurry”.

Overall, “everything seems to indicate that little progress will be made on this front until after the local, regional and European elections of 26 May”. There is even the possibility that we could see a repeat of what happened in June 2016, when “Spain was forced to hold an election just six months after the previous one, because of the failure to produce a parliamentary majority”.