Baillie Gifford’s extraordinary success has made many of its rivals envious, while those who have missed out on the stellar returns desperately want their scepticism vindicated.

No fund in the Baillie Gifford stable represents their growth-focused style better than its £7.5bn flagship investment trust, Scottish Mortgage (LSE: SMT), and its supremely self-confident co-manager, James Anderson.

SMT is no Woodford

The last year has given Baillie Gifford’s critics some ammunition. The technology stocks that dominate the SMT portfolio faltered, resulting in last autumn’s share-price drop of more than 15%, and it has not fully recovered. The one-year performance has modestly lagged global indices.

As exposure to unlisted equities has been built up to 17% of the portfolio, within sight of the 25% maximum, the initial public offering (IPO) market has disappointed, with Pinterest, Lyft and Uber all falling from their issue price. Has SMT been overpaying for its investments? And, of course, Neil Woodford, also an advocate of private equity (PE) investment, has hit a brick wall, illustrating the risks of investing in illiquid shares. Simon Gaunt, a director at BG, bristles at such analogies. The firm, he points out, invests in established businesses with scale, not the early stage start-ups favoured by Woodford. This does not mean “venture” investing is doomed, just that Woodford has been poor at it – unlike life-sciences investment trust Syncona, for example.

SMT is invested in Lyft, but not in Uber or Pinterest. The route to profitability for ride-hailing companies is not clear at present, but few doubt it will emerge and that ride-hailing is here to stay. In 2012, the share price of Facebook halved after an over-hyped IPO, but then soared after doubts about its potential on mobile platforms and the monetisation of its services were resolved.

The volatility of the tech sector has been masked by its long-term performance, but early investors in Netflix regularly saw their share price halve. Share prices, as last year, are prone to get ahead of events, but fast growth means that valuations soon catch up. In short, scepticism about prospects and valuations have been a regular feature of tech’s long bull market.

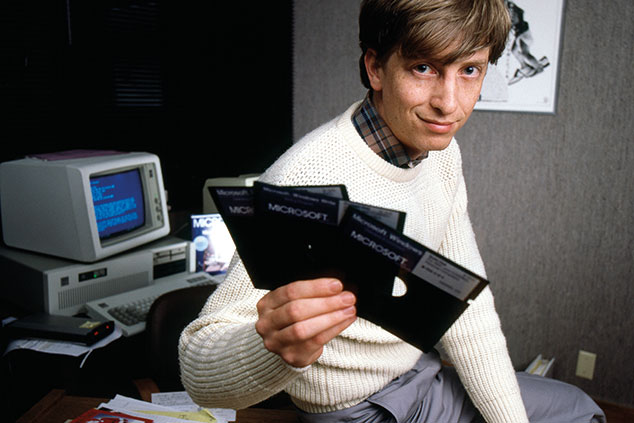

Anderson argues that “growth investing is widely denigrated and value investing regarded as the one true faith”. Yet, “the world changed in the late 1980s when Microsoft listed. The marginal cost of its software licences was zero, bringing in an era of increasing returns to scale and market opportunities unrestricted by production constraints”. Investors have yet to adapt to a world in which business models are not built on the existing economic infrastructure but bypass them, making nothing safe. For example, Anderson thinks that progress in solar and battery technology, with efficiency improving 20% each year, could bankrupt the fossil fuel industry in ten years.

Don’t cut yourself off

As for SMT’s focus on PE, “more than half the potentially great companies we see are private. Investors who shun PE will cut themselves off from the dominant force for progress. More over, these are not small companies and will not go public till very late.” As for the threat from government regulation, “there is no historic evidence that regulation helps smaller companies or is bad for investors.

“The future will be very different from how the average fund manager sees it,” says Anderson. The implied message is to be wary of “cheap” shares that will not necessarily bounce back as the business cycle matures and invest in “reassuringly expensive” companies that are better positioned for change. SMT shares, at a small premium to net asset value, are worth buying.