What did the Apollo programme cost?

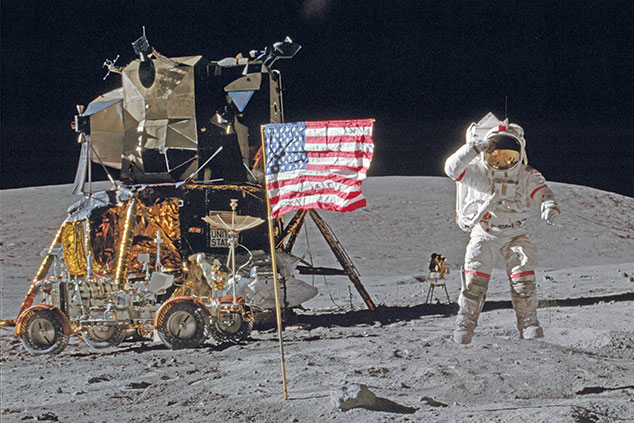

Far more than any government would think of spending on space exploration today. The Apollo programme, which ran from 1961 to 1972 , and achieved its goal of putting astronauts on the moon for the first time, cost around $200bn in today’s money. By 1967, the programme was consuming an astonishing 4.4% of the entire US federal budget. That’s marginally less than the UK currently spends on its entire defence budget. And it’s vastly more than the 0.5% of its budget that the US spends on its national space agency now. That 1960s spend, of course, was part of the Cold War space race: putting two men on the moon in July 1969 was a great show of American power after the Soviet Union sent the first man into space in 1961. It captivated the imagination of 600 million people watching on television, and appeared to be, as Neil Armstrong observed, a “giant leap for mankind”.

Was it a giant leap?

It remains one of our greatest technological feats. And five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the moon. But since December 1972, when Apollo 17 returned home, no one has been back. Human ventures have been restricted to low Earth orbit, and in particular the International Space Station. David Parker of the European Space Agency draws a parallel with the race to reach the South Pole in the early 1900s.

What’s the parallel?

There was an international competition to reach the South Pole and “then no one went back for 50 years”, says Parker. Antarctica was finally opened up by technological advances relating to motorised vehicles, air transport and radio, which made the construction and operation of bases there possible. Equally, we are now approaching that stage with our exploitation of the moon. Advances in machine learning, sensor technology and robotics “promise to transform lunar colonisation”, says Robert McKie in The Observer, by reducing the need for a continual human presence and making it cheaper.

Who is leading the process?

Changing geopolitics – a more assertive US, the rise of China and India – is stoking a renewed push back to the moon. In the US, Nasa’s Artemis programme, championed by President Trump, aims to install a manned space station in the moon’s orbit – and use it as a base for putting astronauts back on the moon – by 2024. China plans to land people on the moon by 2035. India hopes to land a craft on the moon. But the role of private enterprise is growing fast too. Between 1958 and 2009, almost all of space spending was by state agencies. But in the past decade private investment has grown to $2bn a year, or 15% of the total. That growth is part of broader trends suggesting that the next 50 years of space exploration will look very different from the first.

How so?

Falling costs, emerging technologies, Chinese and Indian ambitions, and a new generation of entrepreneurs “promise a bold era of space development”, says The Economist. The coming age will involve the maturing of two new commercial models that already exist: the big business of launching and maintaining swarms of communications satellites in low orbit; and the niche one of tourism for the rich. In the long run it might also involve mineral exploitation in the form of asteroid mining, and even mass transportation and colonisation. “It used to be a space race between countries, and now it’s a space race between billionaires,” says Anoop Menon, a professor at Wharton. Elon Musk is “running SpaceX with the goal of colonising Mars and making humanity a multi-planetary species”. Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic plans to go public later this year, with a valuation of around $1.5bn.

How big is the space market overall?

According to estimates by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, the total size of the space-related market last year – ranging from the manufacture and use of infrastructure, to space-enabled applications such as satellite phones and weather services – was $339bn. UBS thinks annual revenues will be around $800bn by 2030. Merrill Lynch reckons that, due to rapid growth in satellite deployment, ancillary services and launch capabilities between now and 2045, the market will expand eightfold to $2.7trn, and produce “more advances in the next few decades than throughout human history”.

What are the key areas?

In terms of the moon, Nasa is encouraging the growth of a network of private companies capable of transport and delivery – such as Astrobotic, which announced a $79.5m contract with Nasa in May. The later, second phase of moon development will be an even bigger commercial opportunity, says Richard Waters in the Financial Times. If there is as much “frozen water at the moon’s poles as many hope, it could… be separated into oxygen and hydrogen to make rocket propellant, turning the moon into a fuel stop for future missions to Mars”. Mining precious metals left by asteroid strikes is also a potential bonanza.

Which firms could benefit?

In the space sector more broadly, a key current growth area is nanosatellites (launched into low-earth orbit, 500km-2,000km above Earth – far below the 36,000km “geostationary” altitude of conventional communications satellites). Players include Rocket Lab, which has invested heavily in a launch site in New Zealand, Planet Labs, Fleet Space Technologies and Spire. Established names investing heavily in satellite broadband are Inmarsat, Viasat and OneWeb, a US-start-up backed by SoftBank and Virgin.