What is the national grid?

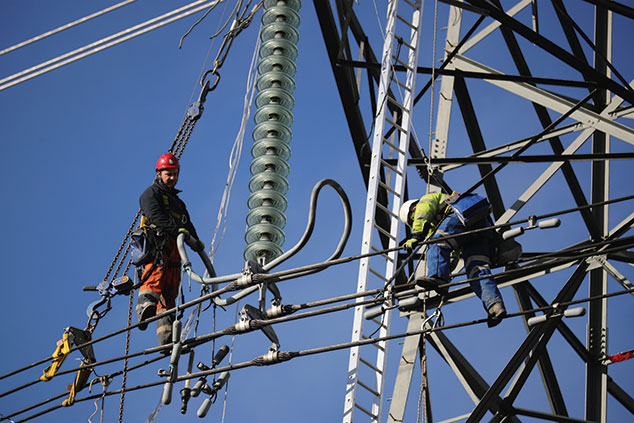

It’s the high-voltage electrical power transmission network for Great Britain (but not Northern Ireland, which is part of a single electricity market with the rest of Ireland). The grid connects power stations and major substations via a system of pylons and thousands of miles of electrical cables, a system which in theory means that electricity generated anywhere on the grid can be used to satisfy demand anywhere else. The idea is that fluctuations in supply and demand are smoothed out and the lights stay on across the whole country.

When was it set up?

The origins of the grid lie in the Electricity (Supply) Act of 1926. Prior to that, Britain’s nascent electrical supply industry was inefficient and fragmented. The Act created the Central Electricity Board, which constructed Britain’s first synchronised, nationwide grid. The grid was nationalised by the postwar Labour government of 1947 and remained in public ownership until 1990. Today it’s owned by National Grid, a stockmarket-listed private company that is accountable to the regulator, Ofgem. It’s so much part of the fabric of everyday life that it seems almost inconceivable that an electricity supply system could be run any other way – and almost incomprehensible when the system suddenly fails, as it did earlier this month.

Why did it fail?

On 9 August, Britain’s worst power cut for more than a decade saw 1.1 million households and businesses in several parts of England and Wales without electricity for almost an hour. The outage, which began at around 5pm on a Friday evening, disrupted traffic lights in parts of London, plunged Newcastle airport and Tyneside’s Metro system into darkness, closed parts of Ipswich hospital and left hundreds of people trapped on trains on the East Coast Main Line into King’s Cross station in London.

What caused the power cut?

It’s too soon to be definitive about what happened: National Grid, Ofgem and the department for business and energy have all launched investigations. However, all indications, including National Grid’s own preliminary assessment, are that the outage followed lightning strikes on part of the network near Cambridge. Lightning strikes are common events: National Grid’s infrastructure is hit by them on average three times a day and they rarely cause serious problems. But on this occasion they appear to have caused massive outages within seconds of each other at two separate electricity generators about 100 miles apart – namely RWE’s gas-fired Little Barford power plant in Bedfordshire, and the world’s biggest offshore wind farm, Hornsea, owned by Orsted, off the eastern coast of England in the North Sea.

Which in turn caused the power cuts?

The combined lost capacity, of more than 1,300MW, was enough to cause such a massive and instantaneous loss of frequency (a measure of energy intensity) in the grid, to well below the targeted constant of 50Hz, that automatic safety processes kicked in, cutting off 5% of the grid’s supply to avert a wider shutdown. It’s not yet clear why the lightning strike caused the twin generators to go offline: in each case the firms concerned have blamed technical errors that can be corrected (and National Grid has been happy to share out the blame). But according to Professor Dieter Helm, a government adviser on energy policy, “the key point is that the power cut should never have happened in the first place. If power cuts can happen when just two power generators drop off, then something fundamental has gone wrong.”

Which was what?

There wasn’t enough reserve supply available to step in, stabilise the frequency and meet demand. At the time of the outages, National Grid had only 1,000MW available, far less than the capacity lost. According to National Grid, which says the UK has, statistically, one of the most reliable energy networks in the world, this was a “rare and unusual event” of a kind that has happened only three times in 30 years. But the fear is that it could become a lot more common. Indeed, there are worrying (albeit unconfirmed) reports that the national grid suffered three blackout near-misses in as many months, with outages in May, June and July, all of which were greater than 1,000 MW.

Are renewables a factor?

National Grid says not, but some energy experts aren’t so sure. According to Tom Edwards of Cornwall Insight, a greater reliance on renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar – which accounted for a third of electricity generated last year – do make it harder to balance supply and demand across the grid. That’s because renewables are more prone to drop off suddenly, and thus they decrease the “inertia” that acts as a shock absorber in the system. This means more fluctuations in supply and greater volatility in frequency.

What should be done?

Some experts, such as Colin Gibson, a former director of National Grid, argue that the government needs to step in and limit the level of renewables in the energy mix – an unlikely prospect given the UK’s commitment to a net zero carbon economy by 2050. Others point out that existing battery technology could mitigate the risks involved. National Grid is already working on a plan to ensure that the system is tooled up to deal with a scenario where 100% of power is from zero carbon sources by as early as 2025. The simplest solution, argues Ed Cropley on Breakingviews, would be to beef up supplies of back-up batteries. Storage units with a 1,500MW punch would cost £500m a year, he calculates – or around £6 on every household’s annual energy bill. “Whether Britain’s politicians would have the guts to sell that – and even whether Ofgem will identify the guilty party – is another matter.”