Back when he was chancellor, George Osborne embarked on the process of removing tax relief on mortgage interest from buy-to-let loans. The removal of that relief – which continues – has really started to bite now.

More than anything else – certainly more than Brexit – it’s the removal of this tax relief that has taken the heat out of the UK housing market and contributed to the slowdown in price growth over recent years.

Other changes, such as higher rates of stamp duty, increasing scrutiny of loan-to-value ratios, added protection for tenants, and a less hospitable environment for wealthy foreign investors, have all contributed to a decline in the appeal of buy-to-let and a rise in the number of landlords leaving the market.

Landlords – you ain’t seen nothing yet

However, this is nothing compared to what could happen under a Labour government, it seems.

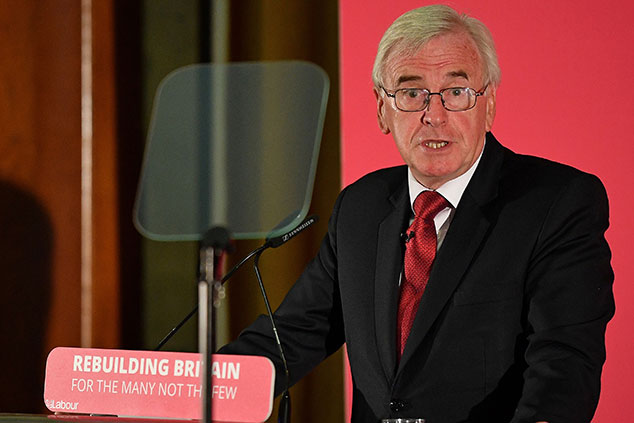

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell suggested in a conversation with the Financial Times earlier this week that Labour could introduce a “right-to-buy” scheme which would allow private tenants to buy the home they are currently renting.

There aren’t many details and it’s not an official policy yet. But the idea is modelled loosely on the scheme introduced by Margaret Thatcher that gave council tenants the right to buy their council house at a discount.

How would it work? McDonnell doesn’t elaborate much in the interview. “You’d want to establish what is a reasonable price, you can establish that and then that becomes the right to buy… I don’t think it’s complicated.”

Of course, a “reasonable price” may be quite different to the “market price”. It’s worth remembering that the official “right-to-buy” discount is up to 35%. So it certainly implies that tenants would be able to purchase at below-market value.

So not only could landlords be forced to sell up, they’d be forced to sell up at a state-specified price. That’s a very different world to the one that any of us has been used to in the last few decades.

Hansen Lu of Capital Economics also points out that while some tenants might be pleased about the idea, overall “the outcome for tenants would be regressive – richer tenants would gain a windfall when purchasing a rented home, but poorer tenants would rent at higher prices and see no benefit.”

And of course, if this was introduced then the idea of a) becoming a landlord or b) remaining a landlord, would be incredibly unattractive. So you’re looking at potentially a big sell-off of properties, driving wider house prices down, plus potentially a big rise in rents on the remaining properties, to offset the risk of being forced to sell further down the line.

In short, while the policy seems unlikely to get the go ahead, if it did, “it could have a serious detrimental effect on landlords, tenants, and the general health of the rental market,” notes Lu.

You very much can go wrong with bricks and mortar

This may well just be a kite-flying exercise, and it’s easy to brush off. But that would be a mistake.

This is yet another very good reason for investors in the UK to shake off the idea that “you can’t go wrong with bricks and mortar”. Property is not only illiquid (ie, hard to sell in a hurry), but it is also a prime political target.

When one of the main political parties of the day is apparently not even remotely nervous about discussing what amounts to expropriation of private property, right ahead of a probable general election campaign, landlords have to accept that they are being fitted up as public enemy number one.

It’s ironic, given that pretty much all of the buy-to-let boom happened under Tony Blair’s Labour Party, who were more than happy to see house prices rising, generating the “feel-good factor” that helped to keep them in power for so long.

But times have changed. If you are considering a retirement strategy that relies heavily on rented property, be sure that you are fully aware of the risks that entails. And if you’ve not already embarked on such a strategy, we’d suggest that you don’t – invest in something less politically contentious.

We’ll have a lot more on what a Labour government could mean for your money in coming issues of MoneyWeek magazine. Get your first 12 issues for £12 here.