This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

It’s been another exciting week on the political front.

Will the US and China come to sort of trade deal? Will the UK and the EU come to some sort of Brexit deal?

I don’t know. Sorry.

But I think it’s worth looking at something else that happened this week – something that slipped under the radar a bit.

But which could potentially be quite bullish for markets.

The Fed prints money but it’s not money printing

The Federal Reserve – America’s central bank – did something interesting earlier this week.

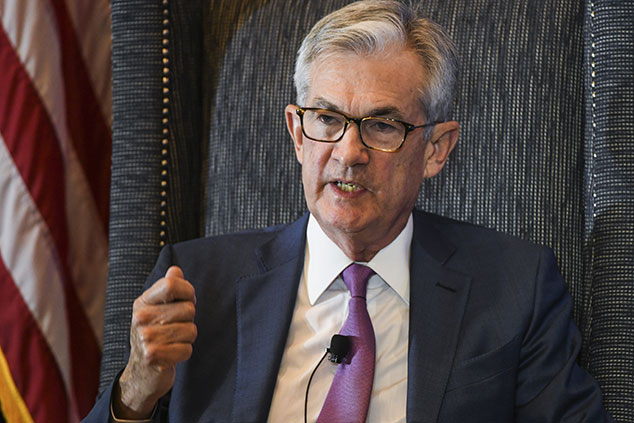

Fed boss Jerome Powell was giving a speech to a group of academics and economists on Tuesday. He gave his usual “the economy is doing well but we’re going to cut interest rates at the next Fed meeting this month” view of things, which didn’t surprise the market at all.

However, what did come as a surprise was his decision to start printing money to buy bonds again.

This, he said, shouldn’t be mistaken for quantitative easing (QE – printing money to buy bonds). Oh no, said Powell. “I want to emphasise that growth of our balance sheet for reserve management purposes should in no way be confused with the large-scale asset purchase programmes that we deployed after the financial crisis.”

So what’s going on then? This all boils down to problems in the “repo” market. Put simply, banks lend money to one another over the very short term to cover things like immediate needs for cash. Usually, there are no problems in this market because no one is going to go bust overnight and so no one is worried about lending their cash for this period of time.

Those of you with long memories will recall that we knew things were getting bad in the run-up to the 2008 crisis because banks no longer wanted to lend to one another overnight because no one knew who owned all the dodgiest mortgage bonds.

So it was a bit scary last month when we started to see similar spikes in repo market borrowing costs. There was also lots of dark talk, referencing the credit crisis, about how maybe something sinister was going on.

This isn’t QE4 so much as QE three-and-a-half

Much as I like a spooky markets story, I don’t think this one is warning of imminent danger.

I don’t want to get into the mechanics of the repo market because it hasn’t half caused a lot of furious arguments on Twitter in that way that only something relatively minor but also extremely arcane usually can.

I will delve into it in more technical terms if I feel that there’s more to it. But for now, I think the easiest way to look at it is that our financial plumbing is now dependent on central banks sticking their oars in much more aggressively than they used to, in order to keep everything flowing smoothly through the pipes.

When the Fed did QT (quantitative tightening) – effectively draining the tanks of what it considered to be excess liquidity – it just showed up how rickety the whole thing was.

That’s not very encouraging. But equally I suspect it is evidence of a longer-term problem rather than an imminent systemic meltdown. And also, it’s not really surprising that the monetary system is pretty rickety now, given that it has been driven to extremes that few, if any of us, ever really contemplated a little over a decade ago.

So is this QE4, as some people have called it? I probably wouldn’t go that far. Yes, in terms of the mechanics, this is the same sort of thing as QE – the Fed is expanding its balance sheet.

But QE4 suggests that this is something that’s being done with the goal of driving interest rates down or “stimulating” the economy. This is more about maintaining the current level of liquidity and stimulus in the system, and avoiding monetary policy inadvertently becoming tighter.

You can argue that this is semantics but I don’t think it is. QE4 would arguably put a rocket up the stockmarket and also from these levels, you’d expect it to dent bond prices (ie, drive yields higher, in expectation of inflation). As it stands, I think the impact is not that extreme. You could maybe think of it as QE three-and-a-half

Of course, that’s not to say that it doesn’t pave the way for easier policy further down the line. Indeed, we’ve already established that the Fed is viewed as 100% certain to cut interest rates again later this month.

And more to the point, it makes the monetary backdrop much more conducive to a rally should either of the two things we mentioned in the introduction – a China/US trade deal, or a UK/EU Brexit pathway – actually inspire a bit of investor optimism.

On the investment implications of Brexit, by the way, if you haven’t already subscribed to MoneyWeek magazine and you want to get up to date on what’s been going on – well, now is the perfect time. We’ve compiled a special report based on all of our most recent coverage to get you up to speed quickly and painlessly. Not only that, but you can get your first 12 issues for £12, too – sign up here now.