“Is value investing dead?” We’ve heard this plaintive cry many a time during the past decade, as growth stocks (flashy, expensive stocks) have trounced value stocks (dull, cheap ones). Several reasons have been proposed for this performance gap, from the idea that interest rates have hit a permanently lower plateau, to the theory that the nature of “book value” (see below) has changed as intangible assets such as “intellectual property” and “network effects” become more important than tangible assets such as factories. Now we have an interesting new take to add to the mix – that it’s all down to revolutions.

“Value is dead, long live value,” a recently published paper by Chris Meredith at O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, uses a theoretical framework described by Carlota Perez in her 2002 book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. Perez has studied what happens to markets and economies when a disruptive technology – such as the car, or the internet – takes off. The process of adapting to and embracing the new technology goes through various phases over a lengthy cycle (lasting several decades), and Meredith argues that it’s in the middle of this process – when innovation is peaking and the new technology is going mainstream – that growth outperforms value.

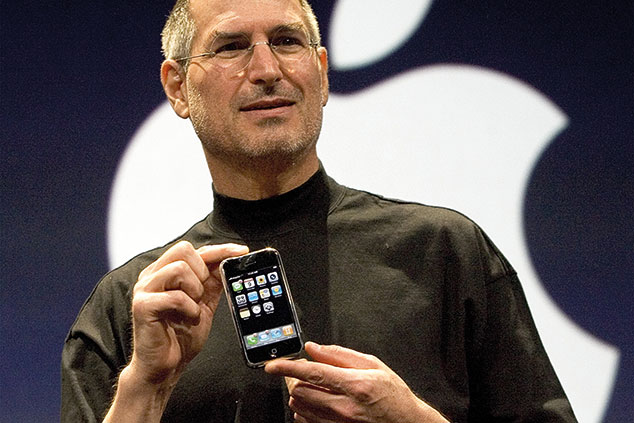

Growth stocks – those backing the exciting new technology – take off, while value stocks – darlings of the former cycle, now facing disruptive new rivals – are left behind. So, for example, while manufacturers thrived during the boom era of the car and mass production, utilities languished. This helped to drive a period when growth outdid value for 15 years between 1926 and 1941. This time around, the leaders are tech stocks such as Apple, while the laggards are financials. However, this won’t go on forever, not if history is any guide.

As the “innovations move to maturity”, the wider economy starts to pick up the pace, and as a result cheap value starts to outperform expensive growth again. When will it happen? It’s impossible to say, but as Meredith notes, “given that it’s been 12 years, it certainly seems like this period is getting a bit long in the tooth”. In short, value is not dead – this has been a particularly rough period, but by no means a unique one.

As for what value investors should be eyeing now – out-of-favour financials might be worth a look. Note that this has been one of the big drivers of the performance gap between the US and Europe: the US market is top-heavy in tech, whereas Europe’s financials have struggled. One interesting investment trust investing in the sector is Polar Capital Global Financials Trust (LSE: PCFT), currently trading on a discount of 5%.

I wish I knew what book value was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Book value is also known as equity, shareholders’ funds, or net asset value (NAV). It is the value of all of a company’s assets, less all of its liabilities (debts). Book value is sometimes used as an estimate of what a company would be worth if all of its assets were sold for their balance-sheet values. If you know the book value, you can get an idea of how cheap or expensive a share is by dividing the share price by the book value per share (hence the price/book, or p/b, ratio).

A p/b of below one means that – technically speaking – you can buy the company for less than its assets are worth on paper. So if you could buy the whole company, you could sell all of its assets, and still profit. One problem, however, is that the book value may not reflect what you would actually get for those assets. For example, there may be a lot of “intangible assets”, such as goodwill (often relating to the value of a brand).

The value of intangible assets – unlike a factory or a piece of land – can be hard to measure objectively. They may in fact not be worth very much at all – particularly not in a fire sale. So an unusually low p/b could signal a company in trouble, rather than a potential bargain. By subtracting intangibles from book value you get a more conservative number, known as “tangible” book value, based on hard assets, such as land, stocks and cash. If you can buy a stock for a lot less than this figure, it may be a bargain.

Yet note that, as a paper last year from US money manager O’Shaughnessy Asset Management (OSAM) points out, intangible assets – such as research and development spending – are key parts of today’s companies, and they can often be undervalued too. OSAM found that from 1993 to 2017 stocks that looked expensive on a p/b basis, but cheap on other measures, tended to beat the wider market. In other words, as with any other measure, don’t rely on p/b alone, and understand its limitations.

See more definitions like this in MoneyWeek’s financial glossary