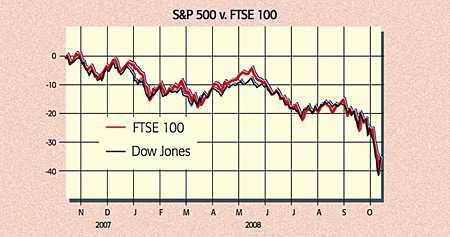

This week we were spared another Black Monday. Last week saw a historic wipe-out: the S&P 500 slumped by 18%, its worst week since the 1930s, and the FTSE 100 lost over a fifth of its value. But on Monday there was a record rebound in Europe and an 11.6% jump in American stocks, the best day since the recovery from the 1929 crash.

“The dithering has ended,” as Economist.com puts it. Last week investors feared that the intensifying squeeze in the money markets threatened to cut off funding for banks and companies (we highlighted some examples in last week’s issue) and thus cause a global economic meltdown. Now Europe has followed the UK’s lead in bailing out its banking systems, with the continent pledging a total of just over £1trn. As in the UK, Europe will guarantee interbank debt and inject capital into the sector. America is to pledge $250bn to recapitalise banks and will also guarantee interbank loans.

This finally addresses the cause, not the symptoms, of the problem. Leaders have now effectively admitted that the banking crisis, and accompanying liquidity problems, is rooted in worries about solvency and capital. These should be addressed by systemic recapitalisation, as Gillian Tett points out in the FT – not “ever-more creative liquidity tricks” from central banks. While stocks rallied, interbank rates eased. The three-month euro rate eased by 0.07% on Tuesday, the largest decline since last year. Still, this emergency treatment “is no more a cure” for the credit crisis than a trip to casualty “can be called a cure for a heart attack patient”, says Randall Forsyth in Barron’s.

It should avert a total meltdown in the financial sector. But as Mike Lenhoff of Brewin Dolphin notes, the “forces of economic contraction were set in motion long ago by the credit crisis”. A global recession is still on the cards. Tighter credit in Europe, heading for its first recession since the euro’s inception, is prompting companies to rein in investment, which, having fallen in the second quarter, won’t recover until late next year, predicts Credit Suisse. That bodes ill for employment and consumption. The latter has already slid in the past two quarters.

Banks are likely to need more capital over the next two years, given rising bad debts and further asset write-downs, says Capital Economics. And demand for loans is likely to weaken too. Both lending and the economy look set to keep slowing. It’s a similar story in the US; rattled banks are just beginning to shrink their balance sheets and are thus hardly inclined to boost lending, says Gerard Baker in The Times. Prepare for a “probably nasty recession”.

There is, then, precious little for investors to look forward to. The question is whether they’ve yet factored this in. Citigroup noted last week that analysts expect a 17% rebound in global earnings in 2009, after 2% growth this year. Yet this earnings recession, given the severity of the latest financial squeeze, could see earnings slide by far more than the 25% typical of global downturns (so far profits are down 9% from their peak).

Low p/e ratios based on predicted earnings, then, should be taken with an especially large pinch of salt. A longer-term view of valuations is provided by the cyclically adjusted p/e ratio, tracked by Yale’s Robert Shiller. This averages out earnings over the last decade, thus adjusting for atypically strong profit growth over the past few years. It stood at 15 for the S&P late last week. But it tends to overshoot on the downside in major bear markets. It reached six in 1982, for instance, before the 1982-2000 bull began. In Europe, it’s still around 12. In short, there is still ample scope for disappointment. As Wayne Nordberg of Hollow Brook Associates told Barron’s, “the great credit supercycle” will take “a very long time to unwind”.