“It’s like an unending nightmare,” says Kent Engelke of Capital Securities Management. Another Monday bloodbath reduced most equity indices to new credit-crisis lows this week. The Dow Jones fell below 7,000 for the first time since 1997; the S&P 500 hit a new 12-year low; the pan-European DJ Stoxx 600 fell to a 13-year low and the FTSE 100 slid to 3,500 – a level not seen since the start of the Iraq war six years ago.

“Hardly a day passes that we’re not doused with dispiriting news” on the economy, says Alan Abelson in Barron’s. In America, sales of new houses have hit another record low and the annualised slide in fourth-quarter GDP was revised up to 6.2%, the worst in 26 years. New claims for unemployment benefit have jumped to a 27-year high.

In Europe, a gauge of manufacturing activity sank to another record low just as British manufacturers slashed jobs and output at a record pace. Capital Economics notes gloomily that the lending commitments wrung out of Lloyds and RBS in return for guaranteeing their toxic assets are unlikely to be enough to give the economy a fillip, even assuming there is any demand for new lending.

Meanwhile, a record rights issue by HSBC emphasised that “even what were seen as the better-funded banks are having trouble”, as Jimmy Yates of CMC Markets puts it. And the fourth bail-out for insurance giant AIG in five months – the group lost a staggering $62bn in the fourth quarter, or $465,421 a minute – has fuelled worries that the US government “does not yet know how to draw a line under the crisis”, says John Authers in the FT.

There was also a spate of dividend slashing, with General Electric reducing its annual payout for the first time since 1939. Dividend payouts are expected to tumble by 23% this year, which would mark the worst year since 1938. No wonder, with earnings cratering: the companies in the S&P 500 racked up a collective loss of $114bn in the fourth quarter, says Money.cnn.com. It’s the first ever quarter of negative earnings. Credit markets are also increasingly pessimistic, with interbank rates and corporate bond yields on the rise again.

In short, there is absolutely no good news out there. With no signs of lasting improvement in the financial sector or the global economy, “we’re still desperately searching for a bottom; it’s death by a thousand cuts”, adds John Mar of Daiwa Securities. Investors are increasingly realising that recovering from a burst debt bubble is likely to be a multi-year process. Bloomberg.com notes that options investors, for example, are now paying twice this decade’s average price for protection against losses on American stocks over the next two years.

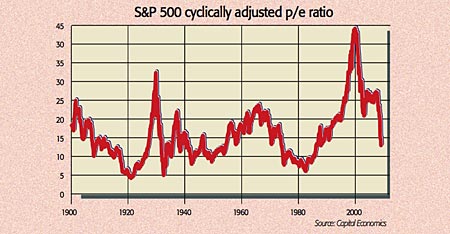

Tom Lauricella in The Wall Street Journal points out that there has hitherto been no “panic selling in large volume” (ie, capitulation), which is typically the hallmark of a market nadir, while valuations also imply further downside potential. The cyclical p/e ratio, which compares the price of an index to average earnings for the past decade (thus taking into account the earnings bubble of the past few years) is at 12 in America, but it has bottomed at six to eight after previous major bear markets. The same goes for Britain’s cyclical p/e, which is also still in double figures.

For 2009, Capital Economics sees the S&P 500 losing another 8% or so by mid-year, while Saxo Bank reckons the FTSE could finish the year just under 3,000. But wherever the bottom is, given that there is still no hint of even “the beginning of the end” of this mess, as Abelson puts it, the best bet is to “stay sceptical” of equities.

The big picture: America’s $1.75trn deficit

Last week, setting out spending plans for the next decade, the US government announced that the US would run a $1.75trn budget deficit this year. At about 12% of GDP, that’s the largest government deficit since World War II. The sum also outstrips the GDP of major economies such as Spain, Brazil, and Australia.In fact, a country with a GDP the size of the US budget deficit would be the ninth-largest in the world. The deficit is projected to shrink to 3% of GDP by 2013, but don’t count on it: this relies on the economy growing by an extremely optimistic 3.2% next year.