General Electric spooked investors with a dividend cut as its ‘shadow banking’ system came under strain. And it won’t be the only one, says Cris Sholto Heaton.

Two weeks ago, US bellwether General Electric (GE) slashed its dividend by 68%, ending its proud record of maintaining the payout every year since the Great Depression. The company is trying to conserve some $9bn a year in cash and hold on to its coveted AAA credit rating. Yet even after taking this drastic step, the odds are that the credit rating agencies will cut its rating by at least one notch in the near future.

For many GE shareholders, this is a shock. The firm is one of the world’s biggest names and the owner of several renowned, cutting-edge manufacturing businesses. Yet Monday’s Wall Street Journal carried the stark headline: “A crisis of faith in GE.” Undoubtedly, all manufacturers are facing a tough time as sales slump, but why is a legendary firm like GE under such severe pressure?

It all comes down to the shadow banking system. This is the new buzz-phrase to describe the huge growth in lending that took place off corporate balance sheets, and was barely regulated over the last few years. But this is not the shadow banking system of special investment vehicles and hedge funds that has caused so much trouble for the financial sector. This is another shadow banking system, still largely concealed behind the first. The financial sector allowed consumers to run up enormous mortgages and credit-card debts, and let private-equity firms gorge themselves on leveraged buyouts. But there was an enormous run up in lending within the ‘real’ economy as well. In the last two decades, many solid, staid industrial firms have slowly transformed into something not that far from being banks themselves.

That could spell bad news for investors who are congratulating themselves on having avoided the Lehman Brothers of this world. Devastating as the crisis has been, until recently most of the damage has been inflicted on banks. But as the recession worsens, we’re likely to see bad debt losses pop up in some unexpected places. Even for those who avoid the worst of the losses, profits are likely to suffer a severe – perhaps permanent – dent in this new, lower-debt world.

How General Electric turned into a bank

But let’s start with GE. Firstly because, although it’s exceptional, it illustrates what’s been going on rather well. And secondly, because GE is one of the world’s most widely held shares. If it’s in your portfolio, you may well be wondering what all the fuss is about. Why has the dividend been slashed? Why have the shares fallen 75% over the past year? And why has the cost of credit default swaps to insure GE’s debt against default risen four-fold in six months?

At the heart of the problem is a simple fact: GE is not just an industrial group. It’s an industrial group locked in unholy union with a very large, opaque financial institution. GE Capital Services (GECS), which is a wholly owned subsidiary of GE, is very big, both in its own terms and as part of GE. In 2007, at the peak of the boom, it contributed more than 40% of GE’s earnings. With $661bn in assets, not only does it account for more than 80% of the combined group’s assets, but it is as large in its own right as defunct UK bank HBOS was (although that’s not to say the two are directly comparable).

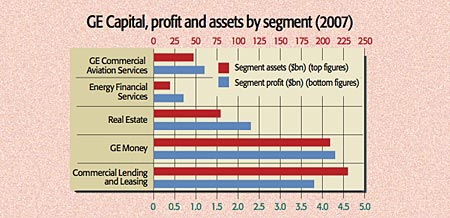

So what exactly does GECS do? A lot, as you can see in the chart below, which shows GECS’s peak profits and assets in 2007. But it’s the real-estate arm – which not only includes commercial real-estate lending, but also makes direct investments in property – and consumer lender GE Money that are drawing the most attention. Investors are questioning whether the property portfolio has been written down sufficiently and whether allowances for consumer debt losses will be big enough as the credit bubble bursts worldwide.

GECS has always been pretty opaque, especially under former CEO Jack Welch. Since Jeffrey Immelt took over in 2001, he’s dumped a number of GECS businesses, including insurance and, in 2007, US mortgage lending. Transparency has improved a little – but only a little.

And what GE does disclose isn’t reassuring. For example, it doesn’t really break down GE Money’s mortgage portfolio – but we know that 30-day delinquent loans rose from 7.26% at the end of 2007 to 10.74% by the end of 2008. Also of concern is that, at the start of 2008, GE Money’s management boasted to Euromoney magazine of having $23bn in assets in eastern Europe, and having grown its business there at 30% a year since 1999. With the region now imploding, this raises big questions about the quality of the loan book.

Of course, the lack of clarity isn’t just down to GE. Because the firm was seen as an industrial stock, it was usually covered by industrial-sector analysts who didn’t have the expertise or the desire to poke around in the inner workings of GECS. But they’re certainly paying attention now, as GE’s actions have consistently shown that it’s weaker than it claims. In October, for example, it raised $15bn in new capital – including $3bn from Warren Buffett in pricey preferred stock paying a 10% dividend – just days after Immelt repeated that he saw no reason to raise capital. GECS’s segment earnings are down 30% year on year and charge-offs for bad debt are rising. And there’s that dividend cut – again, hot on the heels of GE denying that one was on the cards. At last, analysts are asking the questions they should have done all along. How good is the loan book? Are the write-downs conservative enough? How much capital does GE Capital have?

The last question is a big one. GE has always said that the finance arm has a solid assets-to-equity ratio, giving it lots of scope to absorb bad debt write-offs. But in these paranoid times, investors have noted that this includes a fair amount of ‘goodwill’, a slippery accounting term that can’t be used to pay the bills. If you start being more conservative and focus on tangible common equity (shareholders’ equity less goodwill), the cushion roughly halves. To help allay these fears, GE injected another $9.5bn into GECS this quarter and insists that the overall group has no need to raise yet more capital. “On a tangible common equity basis, we are fine,” chief financial officer Keith Sherin told The Wall Street Journal. With a tangible common equity-to-assets ratio of 5.3%, “our tangible common equity for GE Capital is higher than any of the big banks”. But in a world where many banks are utterly insolvent, that’s probably less reassuring than he intended.

And of course, there’s the question of what happens when it loses its prized AAA credit rating. Because it’s likely that GE Capital’s stellar results were in part due to being able to use GE’s AAA rating to raise funds more cheaply than it could have done as a stand-alone firm, thus boosting its lending margins. (That’s much the same trick HSBC thought it could pull with subprime lender Household Finance, and look how that’s turned out.) Once GE is no longer rated AAA, it’s likely to put a permanent dent in its finance earnings.

Indeed, even now no one is freely lending to it as an AAA credit: the group has had to make heavy use of US government debt guarantee programmes to bring down its borrowing costs. What’s more, GE notes in its latest filing to the US Securities and Exchange Commission that “various debt instruments, guarantees and covenants would require posting additional capital or collateral” if the rating were cut far enough (a four-notch cut to below AA- would require $8.2bn). No one is yet suggesting that GE is another AIG, where escalating demands for collateral sent the insurer into a death spiral, but this would tie up more cash and further hurt earnings.

General Electric is not the only one

While the frenzy surrounding GE is uncomfortably reminiscent of the last days of Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and AIG, it’s good that these questions are finally being asked. But it would be even better if analysts were asking them of some of the other industrial firms on their watch. GE is exceptional in the scope of its finance activities, but a number of peers have quietly made lending a cornerstone of their strategy. Many big manufacturing firms have helped consumers and business to buy their goods by giving them loans or allowing them to lease products long-term instead of buying them outright. This process is known as vendor financing. These loans to customers are then kept on the firm’s balance sheet or securitised (parcelled up) into asset-backed securities and sold on to investors. The financing for this is either managed directly by the firm, or arranged with a bank or specialist lender. For example, as well as offering vendor finance and leasing on its own goods, GECS provides financing services for other manufacturers.

In some sectors, vendor financing has grown enormously over the last couple of decades. At heavy-equipment manufacturer Caterpillar, financing and leasing receivables as a percentage of assets has almost doubled; peers such as John Deere and Volvo are also heavily involved. Now for most firms, the headline contribution that financial services makes to earnings isn’t as dominant as it is with GE. For instance, BMW’s finance unit contributed 23% of operating earnings in 2007, while for Caterpillar the figure was 13%, and for IBM it was 9%.

But in some cases, focusing on this can understate the importance of financing – because it was only the willingness of these firms to make loans in the first place that allowed customers to buy from them. In other words, without loans, sales would have been lower. At BMW, for example, leased products and customer receivables on the balance sheet have risen 79% in the last five years, while the proportion of sales financed by its financial services arm rose to 48% in 2008, from 45% in 2007 and 43% the year before.

This business model worked well in the boom times: firms got to accelerate sales and, better still, they got to collect interest on those sales. And like GE, the strongest firms were able to use their high credit ratings to keep the cost of borrowing down and earn a decent margin on the gap between their costs and the rates they charged on loans. But as deleveraging continues and consumers and business become less keen to take on debt, this strategy will unravel. For many firms, there’s a good chance that pre-recession levels of sales won’t return for a long time. Even if there is demand, frozen credit markets mean that industrials will find it much harder to use their high credit ratings to raise money cheaply, or to sell on their loans to investors.

Bad debts will rise. We’ve been here before during the dotcom bubble, when companies such as Lucent, Nortel and Xerox borrowed on their own account to extend loans to their telecoms and tech start-up customers, many of which had to be written off. It’s hard to guess what default rates on this financing will be, but they’re likely be higher than expected. Troubled US commercial lender CIT Group, a vendor finance partner for several big manufacturers, announced a one percentage point quarter-on-quarter rise in write-offs in its latest results.

And seemingly conservative lending practices may not turn out to be as dependable as they look. A firm in the equipment leasing or financing line can point to solid collateral. For example, GE says that its commercial aircraft-financing portfolio is “predominantly newer, high-demand models”. But the real market value of this collateral in the middle of recessions, bankruptcies and forced asset auctions may turn out to be somewhat lower than its book value. Firms that have financed rapidly depreciating assets, such as cars and IT equipment, are likely to be among the worst hit here.

Just because a firm uses vendor financing doesn’t mean there’s a bomb waiting to go off in its balance sheet; used prudently, it’s a valuable selling tool. But it would be surprising if we got through this recession without at least one major firm following GE and shocking investors with financial missteps. And many firms that dodge that bullet are still likely to see much weaker sales growth in the future as the financing engine that has driven growth stalls. Indeed, it’s not encouraging that IT firms such Cisco, IBM and Oracle are in fact increasing their vendor financing to maintain sales as their customers struggle to get loans from other sources. As the old saying goes, any fool can sell a dollar for 80 cents – and with default rates already on the rise, that may turn out to be all those loaned dollars are eventually worth.

Two stocks safe from the trend

You shouldn’t necessarily avoid a stock because it makes loans to customers (‘vendor financing’) or has other financial operations. But high and rising use of the tactic, especially in industries where assets rapidly fall in value, can be a red flag. Investors are still underestimating the impact that the end of the credit boom will have on firms that have used cheap credit to drive sales, says fund manager Julian Pendock of Senhouse Capital.

So which groups are least dependent on credit? Pendock favours Italian scooter group Piaggio (IM:PIA) over BMW (GR:BMW). The balance sheet is sound and it doesn’t depend on vendor financing to drive sales; what’s more, it “captures the zeitgeist of clean and green” – hence strong recent sales in America and especially in Silicon Valley, home of America’s ‘early adopters’ of new trends. And, of course, as lending shrinks, many of those BMW buyers who can no longer afford a high-end car will be trading down to less flash forms of transport. Piaggio should profit from this as well.

In the infrastructure space, he favours French power and rail equipment manufacturer Alstom (FP:ALO) over rival Siemens (GR:SIE). The German firm indicated last year that it would begin offering vendor financing after clients began to have trouble raising the cash elsewhere. It’s seen a sharp rise in sales, but operating cash flow turned negative in the latest quarter, suggesting it may have gone in quite aggressively. Alstom chief executive Patrick Kron has emphatically ruled out going down this route. That’s wise, says Pendock; at times like this you want stocks that sell to clients you know will pay – such as governments. Alstom fits this theme nicely.

On the other hand, he is slightly cautious on Tesco (LSE:TSCO), a favoured defensive stock for many investors (and one we’ve tipped in the past here at MoneyWeek). That’s not because it’s selling cornflakes on credit. Quite the opposite: Tesco has benefited from vendor financing by using its clout to force suppliers to offer it more credit (in the form of longer payment periods). The resulting improvement in its working capital needs and cash flow has helped fund big hikes in dividend payouts over the last few years. But “one has to ask how sustainable this is”, says Pendock. If Tesco’s suppliers, under pressure as the economy shrinks, can no longer be pressed for more credit without driving them into bankruptcy, then Tesco’s ability to keep boosting its payout while maintaining its expansion plans must come into doubt.