On Tuesday 10th March, stock markets had a great day, with the Dow storming ahead by 379 points. The consensus immediately opted for the beginning of the long-term recovery or, if not that, a major bear market rally.

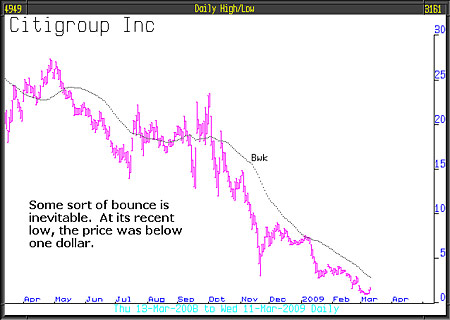

The reason proffered for the market enthusiasm was the publication of an internal memo by the Chief Executive of Citigroup, Vikram Pandit, saying that in the first two months of the year the bank had been profitable. Citi stock rose 35%. The memo was not in depth and mostly concentrated on revenue, ignoring costs and writedowns. But the big rise in percentage terms, when examined on the chart, (see below) from such a catastrophic depressed level is hardly of consequence.

The dilemma facing investors is that this bear market has been going for some while, and prices are significantly lower. A bear market rally, if this is what we have got, looks exactly the same as the early stages of a recovery. The answer to the question “Which is it?” lies in the future price action.

In the short term, the early signs are not very good. Wednesday, which you would have thought might have brought out a flood of buyers, did start off positively; most markets, both in the US and Europe adding 1% or more, but by the close of business FTSE was negative and the Dow largely unchanged – not encouraging for the optimists.

The cause of Tuesday’s surge was most likely short covering, those speculators shorting bank stocks would have been frightened by Vikram Pandit’s remarks and immediately covered their positions. The market doesn’t know what’s going on, so it rises sharply. If it’s the start of a new bull market some big money should have been sucked in, but Wednesday’s action said otherwise!

In 2007 at the stock market peaks, management was applauded for borrowing money and buying back equity, driving share prices higher. This activity was mirrored in the private equity game where investors, even at those ‘heady’ levels, thought it was sensible to take companies private, and expect to sell them back later for much more. We would have thought that well managed companies, when stock markets were so expensive, would have issued new equity, not buy it back; pay down debt and prepare a war chest for future investment opportunities. Instead, they chose to borrow big and buy high, and to hell with the risk. Their incentive, dare we say, was to enhance the value of management’s share options.

Now stock markets are significantly lower, 50% down or more, the debt on companies’ balance sheets is a nightmare and hard to renew, so they have to issue equity to repay the debt. So, now that the stock prices are on the floor, they sell equity. Banks, when considering the renewal of facilities for companies, are insisting on part repayment as part of the package, thus forcing companies to issue more equity, and if they can’t, be forced into administration.

The outlook for dividends is grim, as companies hoard cash. GE recently cut its dividend for the first time since 1938 and Standard & Poor’s have forecast that 2009 will see the worst year for dividend cuts since 1938.

Looming in the background is the spectre of the Japanese stock market, the Nikkei Dow is now at a new long term low since its all-time high in 1990, at price levels last seen in 1982. Could that happen this time around for our markets? To say ‘no’ would be very brave.

Prior to the recent decline, FTSE and most other world stock markets were, since October 2008, in a trading range, the recent move below that trading range does not look overdone. If you look at the 12-month chart for FTSE, you can see how it’s quite possible that it is heading towards 3,000.

The abiding question is, “Is all the bad news in the market?” If yes, we would expect the bear market to end. But we think the answer is no.

• This article was written by

Full Circle Asset Management

and published in the threesixty Newsletter on 13 March 2009