The press never misses a chance to dance on the greenback’s grave these days. So the news that China’s holdings of gold had almost doubled got a lot of coverage last week.

At first glance, this looks like proof that unhappiness with America’s profligate ways is finally boiling over. China is preparing to dump the dollar and switch into something a little more durable. Or so the story went.

Unfortunately for gold bulls and dollar bears, this was a bit of an over-reaction. In the long-term, the US does have a currency credibility problem. But it’s highly unlikely that China – or anyone else – is preparing to dump trillions into the foreign exchange markets any time soon.

As long as this crisis continues, the dollar looks pretty secure…

There’s not enough gold to replace China’s dollars

First, let’s take a closer look at this gold story. According to China’s official news agency Xinhua, state gold reserves are now 1,054 metric tonnes, up from a steady level of 600mt since 2002.

But that doesn’t mean China has bought 454mt in the last few months. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), which looks after the country’s gold, is pretty secretive. It’s quite likely that it has been buying steadily over the last six years, but just hasn’t told us about it.

Secondly, let’s put the amount in context. Even if China bought all that gold last year at the peak price, the cost would be around $15bn. By comparison, its foreign exchange reserves increased by $419bn last year. So any suggestion it is diversifying out of dollars in a meaningful way doesn’t really stack up.

Nor could it, even if that was SAFE’s plan. China’s foreign exchange reserves now total around $2trn. At today’s prices, that’s more than 40% of all the gold above ground today. Any significant move out of dollar and into gold would send the metal rocketing. And if this were the intention, tipping us off that it’s in the market – by revealing its reserves have grown – would be rather stupid.

So nothing in this story suggests the dollar has anything to fear from China at the moment. And neither does anything in the currency markets.

Investors are taking on more risk

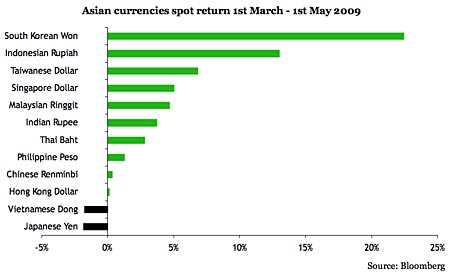

It’s true that the dollar has weakened slightly over the last couple of months. Within Asia, the fall has been greatest against the South Korean won and the Indonesian rupiah. This suggests that investors are becoming a little more willing to take on risk (both the won and rupiah fell sharply during the panic as a result of companies in these countries having substantial dollar-denominated debt).

What’s more, you can see below that US investors were net purchasers of foreign equities in January after being net sellers every month since June. We don’t have March’s numbers yet, but it’s likely they were back in the black as well.

But while investment flows have recovered a little, dollar liquidity remains low on other measures. For example, we can look at FX swaps, which measure the cost of swapping one currency into another.

Borrowing dollars is still expensive

In a US dollar FX swap, an institution, typically a bank, arranges to supply a given amount of local currency for a fixed period to another institution. In return, it receives a corresponding amount of US dollars. For this, the first bank pays the second bank interest on the dollar loan at a market rate (usually the three-month USD London interbank offered rate), while receiving interest on the local currency it has lent in exchange (usually at the three month local currency interbank offered rate).

When markets are functioning well, and supply and demand are balanced, the difference between the two interest rates should be small and relatively stable. But in a dollar shortage, the USD borrower will have to pay a considerably higher rate for the dollar borrowings it receives on its local currency loan. In other words, the difference between the two rates or the “basis swap spread” becomes very negative.

The charts below show five-year USD basis swap spreads for the Japanese yen and the South Korean won. As you can see, the yen spread has come in a little from its widest point, but remains much more negative than usual at -43 basis points (one-hundredths of a percentage point). It’s a similar story in Singapore dollar and Hong Kong dollar spreads.

Bloomberg’s series for USD-won swaps is much shorter, so we can’t see a long-term average – but we can see that -221 bps is far wider than the levels we saw in 2006 and early 2007. (The huge difference between the spread for yen borrowers and won borrowers reflects Korean banks’ high dependence on short-term US dollar borrowings.)

All this suggests that global US dollar liquidity remains poor, despite the Federal Reserve’s efforts to pump more money into the markets. The problem is that just because the Fed boosts the base money supply, it doesn’t guarantee that the wider money supply rises in the American economy and it certainly doesn’t guarantee that global liquidity rises.

Dollars have to make their way into the wider world, either through investment flows or trade. As we saw above, investments flows have turned positive – but only after several months of contraction. Meanwhile, the US trade deficit continues to shrink, as you can see below. While this continues, dollar will stay in short supply.

We can’t change the reserve currency overnight

So for now, we can expect the dollar to remain fairly strong. ‘For now’ is the key phrase there: once the US economy picks up and trade and investment outflows resume, a noticeably weaker dollar is likely. But unless the Fed gets its quantitative easing horribly wrong and we end up with hyperinflation in the US, that’s still a different matter to a dollar collapse.

The dollar is still the global reserve currency. There’s been a lot of talk about it losing this status, but that seems unlikely. A reserve currency is tightly integrated into the global financial system and it takes a long time to shift to a new one. The dollar only formally supplanted the pound after World War II, even though the American economy passed Britain in size in the 1870s.

What’s more, there’s no real contender to replace the dollar. The euro is the closest, but it has plenty of problems of its own. And any idea that the renminbi is ready to take over is a fantasy. China is moving to make its currency more of a factor in international finance, by establishing swaps with other countries that would potentially allow bilateral trade to be settled in renminbi. But these are very early steps.

The renminbi is not yet freely convertible into other currencies. And even if the Chinese government were to make it convertible, there simply aren’t enough renminbi-denominated assets yet for foreign renminbi holders to store their wealth in. A crucial part of the US dollar hegemony is America’s deep and highly liquid capital markets.

Doing the shopping in SDRs

But is there another way? Part of the speculation about the dollar’s future came after Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People’s Bank of China, published a paper arguing for an end to the dollar standard.

He argues that any system in which a reserve currency is also a national currency is flawed. Instead we should use a supersovereign reserve currency managed by a global institution. In particular, he suggests Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which are essentially an internal unit of account at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a handful of other international institutions.

Most economists rejected this idea outright. Now, it’s fair to say that economists don’t have a great track record when it comes to spotting how major shifts in the financial system will play out. Take the 1970s, by when decades of growth in crossborder capital flows had made it impossible to sustain the Bretton Woods system, in which the dollar was pegged to gold and other currencies were pegged to the dollar.

It seems that most analysts thought that switching to floating rates would reduce crosscurrency flows – a conclusion that seems hopelessly misguided given our hyperactive modern foreign exchange markets. According to economic historian Charles Kindleberger in Manias, Panics, and Crashes:

“Most economists had thought that the adoption of floating exchange rates would kill the movement of interest-sensitive capital and that once currencies were floating central banks would be able to follow independent monetary policies without untoward external effects. Economists differed about whether speculative capital movements would be stablizing or occasionally seriously destabilizing; the general view was that fear of exchange losses would deter capital flows. That view proved mistaken; many banks regarded currencies as a new asset class to be traded for a profit.”

Still, it certainly looks like there would be a lot of issues with adopting something like the SDR as a reserve currency. The issues with the renminbi apply on an even larger scale. There are no assets priced or traded in SDRs; not even bank accounts in SDRs. While we can never be certain about these things, the prospect of SDRs – or anything else – replacing the dollar in the next few years look very remote.

In other news this week …

| Market | Close | 5-day change |

|---|---|---|

| China (CSI 300) | 2,623 | +1.9% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 15,521 | +1.7% |

| India (Sensex) | 11,403 | +0.7% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 1,730 | +8.7% |

| Japan (Topix) | 847 | +2.0% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 991 | -0.2% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 2,104 | 0% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 1,920 | +3.6% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,369 | +1.1% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 5,993 | +1.9% |

| Thailand (SET) | 492 | +3.7% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 322 | +3.8% |

| MSCI Asia | 83 | +1.5% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 336 | +3.1% |

The latest economic news continued to suggest stabilisation in some Asian economies, but not a rapid recovery. Korean exports were down -19% year-on-year in April, compared with -25% year-on-year in the first quarter. In China, the official Purchasing Managers Index – a gauge of manufacturing sentiment – rose to 53.5 for April, up from 52.4 the previous month; a reading above 50 is supposed to indicate that manufacturing activity is rising. An alternative survey by brokers CLSA that is probably a better gauge of small business sentiment rose from 44.8 to 50.1.

A telecoms deal provided further evidence of warming relations between China and Taiwan. China Mobile, the country’s largest mobile phone operator on the mainland, agreed to pay NT$17.7bn ($530m) for a 12% stake in Far EasTone, the island’s third-largest provider. Taiwan is planning to allow more Chinese investment in local companies and more direct investment by domestic firms in mainland firms as the new Beijing-friendly government gambles on closer economic ties to boost Taiwan’s economy.

And in a fresh sign of improving market sentiment, China Zhongwang Holdings, an aluminium extruder, raised HK$9.8bn ($1.25bn) in an initial public offering in Hong Kong. The IPO was the largest worldwide this year, with investors apparently seeing the firm as a good play on China’s infrastructure-investment stimulus package.

• This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world’s fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here