In the next few days, India’s Supreme Court should begin hearing a long-running business dispute. The details of the case are mundane: a power company rowing with its supplier over the price of gas. But the soap opera surrounding it is anything but dull.

For one thing, the companies are owned by two warring brothers who have been publicly feuding for years. For another, to many impoverished Indians, this is just a spat between rich men and politicians over who gets to exploit the country’s precious natural resources.

So why does it matter to you? It matters because this isn’t just a one-off scandal. It carries important lessons for investors, not just about India but the rest of Asia …

A sorry tale of sibling rivalry

Giant Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries was built up over decades in true rags-to-riches style by businessman Dhirubhai Ambani. When Ambani died in 2002, the business passed to his sons, Anil and Mukesh.

The brothers rapidly fell out over the direction of the company, and by 2005, were unable to work together anymore. So their mother helped broker a demerger of Reliance into two separate groups. Mukesh received the polyester, oil exploration and refining businesses, while Anil took the financial, telecoms and power arms. Among other things, the split included an agreement for Mukesh’s energy business to supply gas from a large gasfield off the shore of northeast India, to Anil’s power business.

The split didn’t solve the problem – the brothers kept feuding, with Mukesh at one point blocking efforts by Anil’s telecoms group to merge with South Africa’s MTN. But it’s the gas dispute that’s really hit the headlines.

Under the original contract, the gas was priced at $2.34 per million British thermal units – the same price at which the rest of the gas from the field was to be supplied to National Thermal Power, a government power company.

Then, in 2007, the government increased the price paid by National Thermal power to $4.20/mmBtu, because of higher energy prices. Mukesh’s firm, argued that as the government price for the gas was being raised, it had a right to start charging Anil’s power division more too.

Anil’s group took the case to court and won; Mukesh then appealed to the Supreme Court. And that’s when the government stepped in. Worried about the public reaction to the sight of two very wealthy men apparently splitting India’s resources between them, the oil ministry asked the court to annul the original deal. “This gas belongs to the government,” as oil minister Murli Deora told the Financial Times.

State-backed capitalism – one Asian route to growth

It’s a mess – and one which India’s top judges have the unenviable tasking of sorting out.

But I’m not interested in the rights and wrongs of this specific case. What’s more interesting is what the affair says about doing business in India and elsewhere.

The Ambanis are a huge force in the Indian economy. They are often said to account for around 5% of the economy in terms of assets. India’s corporate sector as a whole is dominated by large, family-controlled conglomerates such as Tata, Birla, Bajaj, Mahindra and Essar. Most have had internal feuds at some point.

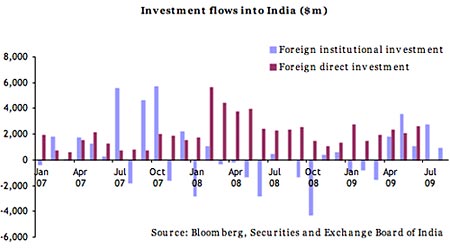

So far the latest punch-up doesn’t seem to be scaring investors off. Investment flows have remained healthy since the excellent election result in May, as you can see below (although it is said to be worrying investors in the energy industry, concerned about a more nationalist approach to natural resources).

However, the fight – or rather the issues underlying it – has some implications for India’s development. At risk of oversimplifying a bit, Asia has embraced capitalism in two main ways. One is that used by Japan and Korea. In these countries, governments allowed companies to knot themselves together in groups of interlocking businesses which supplied and supported each other. These groups are known as keiretsu and chaebol respectively.

The idea was that these firms would then be able to compete in global markets, grow exports and help develop the domestic economy. In short, there was a contract between business and the state – the firms had the right to grow bigger and bigger as long as what they did also served the good of the country.

To a lesser extent, the same happened in Taiwan, although the government didn’t promote the formation of its business groups – known as guanxi qiye – in the same way and many of the large exporters evolved outside of these conglomerates. In Singapore, the government set up many of the major players in sectors such as finance, real estate and semi-conductors. In addition, because of the size of the island and the ruling party’s firm political control, it has been easy for it to shape the economy and business climate to attract foreign firms looking to establish operations there.

Even in Hong Kong, today’s giant conglomerates were born as the hongs – trading houses – that grew up as a result of the British Empire and its need for a global trading network. Today, the territory’s extremely laissez-faire government plays little role in business. But it has no need to because the companies based there had already evolved to suit and support its trade-based economy.

In all of these cases, there were at some point obligations – tacit or explicit – on business to help the state. This is much like the model that China is going down, although state-owned enterprises there are still clearly ‘commanded’ rather than ‘guided’ as they were in the Japanese model.”

Family businesses – the other Asian growth path

Elsewhere in Asia, it’s a different matter. Large conglomerates and family-controlled groups exist in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. In many cases, these are extremely successful, with operations stretching across the region. But at least on the surface, the fruits of their success have accumulated more to their shareholders than to the country as a whole. The same kind of symbiotic relationship between business and the state hasn’t arisen.

There could be any number of reasons for this: perhaps less political vision or greater corruption or maybe racial tension (the successful southeast Asian conglomerates tend to be Chinese-owned in countries in which they are a minority group). Regardless of the cause, some analysts have suggested that this is part of the reason why these countries haven’t progressed as quickly their peers, as the chart below shows – and it’s an explanation that makes some sense.

Given the dominance of family businesses and the fairly weak guidance and assistance that India has given the private sector, it seems to be following the same route as this second group of countries. This could have implications as to how quick and balanced development is there.

Concentration of wealth doesn’t mean development will stall in India or the rest of Asia. America followed a similar pattern during the Gilded Age of the late 1800s, when much of the wealth of its fast-growing economy flowed to the ‘robber barons’ – Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Mellon, Carnegie and Morgan. But ultimately, the imbalance was redressed by trends such as unionisation and by new laws such as the antitrust act which broke up monopolies such as Rockefeller’s Standard Oil.

In the long run, Asian politicians may also feel the need to step in if it seems that only part of the population is benefiting. But this doesn’t always work out the way they might hope. For example, Malaysia has attempted to share wealth more equally by favouring the majority Malays over the richer Chinese and Indian population, but its clumsy approach is in fact, one of the things holding the country back.

So while it’s tempting to conclude that the rest of Asia could do with copying the industrialised economies in trying to achieve closer co-operation between business and state, the wrong kind of action can do more harm than good.

Three lessons for investors

This is a political risk to watch over the very long term, but despite government intervention in the Ambani case, a broader trend doesn’t seem imminent and second-guessing politics is an unrewarding business. So what are the key things that investors should take on board now?

One is that while the northeast Asian model may possibly have worked better in developing the economy, it hasn’t necessarily been great for investors. The keiretsu and chaebol are more interested in propping up allied businesses and on helping the country, and less on delivering decent returns for shareholders. What’s more, having helped the economy develop, they may subsequently have done more harm than good – particularly in Japan – by helping to keep alive failing companies within their clan.

For this reason, I’m not enthusiastic about the huge Chinese state-owned enterprises that most investors – especially funds – hold as investments in China. Instead, I’d generally favour smaller, entrepreneurial private sector firms. As long as the country continues to move towards capitalism, these represent the future of the economy and will deliver the best returns.

The second is that family issues can be a risk and you need to keep an eye out for situations like the one involving the Ambanis. Before their father died, there were no indications of any problems looming, but since the two began feuding, I haven’t even considered investing in a Reliance company. There’s too much likelihood of decisions being made to spite each other rather than for business reasons.

If you can avoid this I’m generally keen on investing in family-run businesses. If the management’s long-term wealth is all tied up in the firm, they should make better decisions than an executive who wants to jack up the share price in the short term to make his options worth more.

But the third point is that you need to be invested in a way that aligns your interests with the controlling shareholders. For example, you should usually be invested in the top of the pyramid of companies, rather than in some tiny subsidiary that might be used to buy or sell assets to suit the broader interests of the group. Investor protection remains weak in most Asian markets and you can’t count on regulators or lawsuits to protect your interests.

The Ambani case shouldn’t scare investors away from India or anywhere else in Asia. But it should remind them that business is done differently there – and investment must be as well.

In other news this week …

| Market | Close | 5-day change |

|---|---|---|

| China (CSI 300) | 3,047 | -4.9% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 20,099 | -0.5% |

| India (Sensex) | 15,922 | +4.5% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 2,377 | +1.9% |

| Japan (Topix) | 969 | +2.3% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 1,174 | +0.9% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 2,884 | +6.0% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 2,643 | +3.8% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,608 | +1.7% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 6,810 | +2.3% |

| Thailand (SET) | 657 | +1.9% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 537 | +3.3% |

| MSCI Asia | 102 | +1.6% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 426 | +1.3% |

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) – which has ruled the country for all but 11 months since 1955 – suffered a heavy defeat in Sunday’s general elections. The political outlook is unclear since its opponent, the Democratic Party of Japan, is defined more by its opposition to the LDP and its desire for a changing of the guard than by a coherent, party-wide ideology; however, there is a real possibility of a dramatic shake-up in Japanese politics and the economy. (Next week’s email will cover this in detail).

Singapore-listed Fortune Reit announced an HK$1.9bn (US$) rights issue to help fund the purchase of three shopping malls in Hong Kong for HK$2.09bn. Investors saw the deal as encouraging since it was the first among the recent run of S-Reit rights issues that was solely about growth, rather than reducing debt and could signal that the sector is turning the corner after the disruption caused by the credit crunch; however the new shares were offered at a hefty 44% discount to the previous week’s closing. At the same time, Fortune also arranged a HK$3.58bn bank loan to refinance expiring debt.

In China, the government responded to worries about malinvestment and overcapacity from the country’s lending boom by announcing new restrictions on fragmented, oversupplied sectors such as steel and cement, while the banking regulator also instructed banks to curb new loans. At current rates, credit extended in August will be lower than in the same month a year ago, the first year-on-year fall since the government relaxed lending restrictions at the end of 2008 in an effort to cushion the economy through the global recession. The mainland China market responded by sliding further, closing down for the fourth week in succession.

Finally, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand were the latest countries to report second-quarter GDP growth. All three posted a strong rebound in line with the rest of the region.

• This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world’s fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here