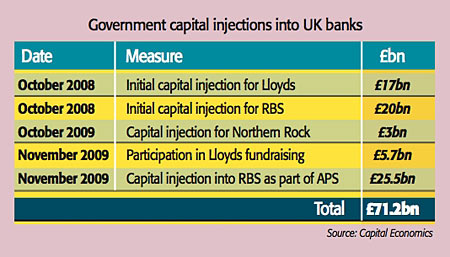

It’s “groundhog day” in the banking sector, as Sean O’Grady put it in The Independent. Last October, the government injected £37bn into Lloyds and RBS to keep them afloat. This week it has made another £39bn of capital available. Most of the money will go to RBS – now the world’s biggest-ever government rescue – taking its total to as much as £53.5bn of taxpayers’ money.

RBS is getting £25.5bn to strengthen its balance sheet and may draw on another £8bn if it needs to. It will keep £282bn of loans in the government’s Asset Protection Scheme (APS), which insures banks against losses on risky assets in return for a fee. Lloyds has been allowed to leave the APS, but will raise capital through a £13.5bn rights issue – a UK record – to which the government will contribute £5.7bn. The government’s stakes in Lloyds and RBS will remain at 43% and rise to 84%, respectively.

As a penalty for all the state aid they have received, and to stimulate competition through new entrants, the banks will have to divest assets comprising almost 10% of the retail banking market over the next few years. RBS will sell its English and Welsh RBS branches under the Williams & Glyn brand and also lose its insurance business. Lloyds will ditch the TSB network in Scotland and the Cheltenham & Gloucester brand. The government will also return Northern Rock (stripped of its toxic assets) to the private sector.

Will the package work?

“The $64bn dollar question,” said Edmund Conway on Telegraph.co.uk, is whether this latest huge cash injection will help the economy by boosting lending to households and businesses. Unfortunately, economists are “rather lukewarm” on this crucial issue. There seems little scope for either to up lending significantly, given their current trading prospects, said David Prosser in The Independent. Both are in the red and facing plenty more write-offs on bad loans.

Worse, RBS is obliged to sell some of its most profitable assets. Note too thatboth expect the economy to improve over the next year. “A double-dip recession (assuming we even make it out of the first part of the downturn)” would delay both banks’ recovery plans further. What’s more, the latest injection falls short of the amount the IMF thinks UK banks need in order for lending to get back to normal, said Michael Saunders of Citigroup. So “even this recapitalisation may not be enough… we suspect credit availability will remain relatively poor”.

A shake-up on the high street?

As far as greater competition in the market is concerned, “it is outrageously cheeky” for the government to claim credit for spurring competition in the banking market, said Nils Pratley in The Guardian. It was really Neelie Kroes, the EU Competition Commissioner, who cracked the whip. As for the changes, “let’s not pretend a revolution is taking place”.

Indeed not, agreed Hugo Dixon on Breakingviews. In some key areas, the sector is still less competitive than it was before the government-induced mega-merger between Lloyds and HBOS. That gave the combined group 30% of both the mortgage and the current-account market. Post-disposals, that falls to 25% of each market. But Lloyds still has a bigger market share than either itself or HBOS had pre-merger.

A tale of two banks

Both Lloyds and RBS were thought to be in big trouble earlier this year. But following this week’s news, it’s clear that Lloyds has pulled off ” a great escape” and RBS has been “clobbered”, said Pratley. Helped along by an improving trend on the bad-debt front and a recovery in the stockmarket, which has given the City the confidence to underwrite a rights issue, Lloyds has managed to avoid the APS and a “severe penalty” from Brussels, said David Wighton in The Times. It may not be too long before Lloyds begins to resemble “a normal bank”, noted George Hay on Breakingviews. But RBS, clearly deemed sicklier by the authorities, “could well be a ward of the state for years”.