If you think the recession’s been bad here in Britain, spare a thought for our troubled cousins across the Irish Sea.

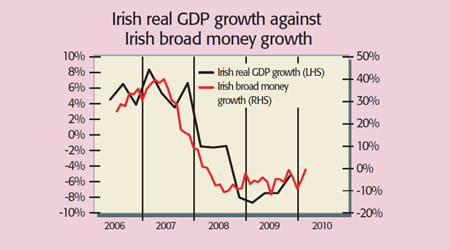

The Irish economy has lost 12.5% of real GDP since 2007 (see the chart below). But because of a severe bout of deflation, nominal economic activity (i.e. before you adjust for price changes) has dropped by a cumulative 19%. Irish house prices are down by 31% over the same period, with Greater Dublin housing down by more like 40%. Overall real estate values, including commercial property, have pretty much halved.

The cause of all this? A banking crisis that keeps lurching from bad to worse.

During a banking crisis, the true scale of the losses becomes apparent only slowly. Banks can’t recognise losses any more rapidly than their weakened capital ratios will allow. So they can only deal with bad loans at the rate they generate trading profits or if they raise new capital to absorb the losses.

Normally, the regulator would demand full disclosure of bad loans. But when the problem spreads to all banks, the whole system is threatened. Taxpayers take a dim view of bailing out the bankers who had been paid huge bonuses to load up on exactly the loans and other risky assets that are now showing such losses. So the regulator has just as much reason as the banks to keep quiet and hope time can work its healing magic.

In Ireland there is still hope that, while painful, the amounts needed to bail out the remaining banks and building societies in private hands are still tolerable. These to date total about €7.1bn, and are currently estimated to hit €11bn-€15bn.

This is bad enough for a country with an annualised GDP of only €160bn. But the losses just reported at nationalised lender Anglo Irish Bank have dwarfed anything Ireland has seen before. Over the 15 months to the end of 2009, Anglo revealed a record e15.1bn impairment charge. This was on top of the €4.9bn loan loss reserve to March 2009 that all but wiped out the bank’s capital base and saw it nationalised in the first place.

Two things about Anglo’s €20bn of bad loan losses leap out at you. The first is that €20bn, a huge sum by anyone’s counting, is vast by Irish standards. We’re talking about 12.5% of the entire country’s annual GDP. The second is that Anglo managed to generate this loss off the back of no more than €73bn of loans. That’s a loss rate, after anticipated recoveries, of 27%. Even in Japan, after nearly 20 years of deflationary workout, bank losses still barely rose above 20% of total lending. As if that wasn’t bad enough, Irish Finance Minister Brian Lenihan warned that the final bill for government support at Anglo Irish might end up another €10bn higher.

But the real fear is that where Anglo leads, the rest of the banks might follow. So the scale of the losses and Ireland’s dependence in the boom on the banking/construction/real-estate complex has seen the Irish adopt a radical solution.

Why Ireland has created a ‘bad bank’

The NAMA (National Asset Management Agency) is a ‘bad bank’ like those used by Scandinavian countries to clear up their own crises in the early 1990s. NAMA is being compulsorily financed by the state pension fund and will acquire bad loans from the banks.

The good news for the Irish taxpayer is that these assets, which might yet fall even further in value, are at least being bought not at face value, but at the estimated current value. The bad news is just how big these discounts to face value are proving to be. For the first round of asset transfers, NAMA has focused on the top ten borrowers. The prices to be paid by NAMA on the first bloc of e10bn of Anglo Irish Bank’s loans worked out at a whopping 50% discount. But Anglo’s assets didn’t seem markedly worse than the rest. Irish Nationwide Building Society had to swallow a 58% haircut on the value of its first tranche of loans. The average across all the banks was 47%.

Of course, forcing the banks to recognise losses on bad assets like this isn’t a bail-out. That comes from the new capital that the banks will have to raise to fill in the holes left by crystallising these losses. This is what the Irish state is having to provide. But a bad bank achieves three things that we might want to think about in the UK.

The benefits of a bad bank

First, by forcing banks to crystallise losses, the Irish at least get to recognise the size of the problem. From there it’s possible to plan the rebuilding.

Second, separating bad loans from the banks and placing them in a state-backed management company stops asset prices falling. US economist Irving Fisher recognised 80 years ago that, in a systemic crisis like this, banks stop lending, so real-estate markets dry up. Bad debts force banks to sell collateral. But no one wants to buy, so the sales are made at knock-down prices. Banks in turn have to write down the value of the property still on their loan books, and a self-feeding deflationary spiral can set in.

Third, taking so many loans off the banks’ books helps solves their funding problems. To understand this and why it’s important, you need to know how banks grew lending so quickly during the boom – and why it all went so badly wrong.

Banks usually source their funds from deposits. This, theoretically, leaves them open to a mismatch on their assets and liabilities: the loans they make are long-dated, while their deposits can be demanded at short notice. In practice, the diversity of retail depositors means this never happens except during bank runs.

But during the boom, central banks kept interest rates too low for too long. Also, regulations on how much banks could lend were relaxed. Low rates meant that more and more people wanted to borrow ever-higher amounts, while weaker rules meant banks could accommodate them.

But low rates and more competition also meant net interest margins (what banks make between their interest costs and what they charge borrowers) came down – in Ireland’s case, from 3.5 percentage points to less than two percentage points (see the chart below). This hit profitability, encouraging banks to increase the volume of loans they made to compensate.

For a bank to make more loans, it must have more funds. The trouble was, there was nothing to fuel a corresponding increase in deposits. So banks from Hawaii to Hungary came up with a neat but dangerous solution: getting increased amounts of their funds from the interbank markets rather than from depositors.

Irish banks’ total lending was no more than 10% higher than total deposits as recently as December 2002. But by December 2009, loans were 75% higher than deposits. This ‘wholesale funding gap’ made the banks vulnerable to a loss of confidence in the interbank markets. When these froze early in the crisis, many hit serious trouble and the UK government was forced to take over Northern Rock.

As part of the repair process, wholesale funding gaps will need to be wound back down. For Ireland that implies a frightening plunge in credit availability, however much new capital can be raised. Ignoring Anglo Irish, the big two remaining banks still had e75bn more loans than deposits at the last count.

But by taking some e80bn worth of loans off the banks’ books through NAMA, this gap can be brought back towards normal.

Could Britain be next?

Things look bad for Ireland now. But the authorities are hoping that they can put in place the foundations for a return of confidence and even credit growth – if they can just get the dire troubles of the past out in the open. It’s a bold step, and we can only wish them luck. Because what we need to consider is what our own bank losses would look like if our banks were to lay bare the true state of their own balance sheets. After all, private-sector indebtedness grew as rapidly here as it did there. Bank margins were under the same pressure. And our wholesale funding gap grew no less outrageously.

If you think ‘it couldn’t happen here’, then try this for size. Lloyds admitted to impairments of £23.9bn in 2009 (about 3.5% of total loan book), with a further £15bn (2.2% of total loans) in loan loss reserves. That makes nearly £40bn (5.7% of loans made) in total. This was more than the others admitted to – RBS had total impairments of just £15bn, while Barclays came in at £8bn. So why were Lloyds’ reported losses so much worse?

Most banks have an incentive to hide balance sheet losses until trading profits can be generated to absorb them – if they didn’t, it would be clear that they have a capital shortfall. Lloyds booked more losses because it had raised £22.3bn in new capital (note the similarity to the £23.9bn in losses) against which it could offset those losses. The others haven’t; instead, they’ll draw out loss recognition over many years (as will Lloyds if this write-off doesn’t cover everything).

Anglo Irish illustrates what happens when a bank is made to reveal all. In the case of Anglo Irish, the Irish taxpayer will provide all the capital needed to cover the losses, so the state is keen to work out what those will be as quickly as possible.

NAMA will take bad assets from all the banks, but only after they have been revalued to today’s price. So Ireland’s banking system losses and economy looks so much worse than ours merely because they have given their banks an incentive to reveal losses now rather than drip-feed the bad news. Ireland today may still be a vision of Britain tomorrow.

• James Ferguson is head of strategy at Arbuthnot Capital.