What makes a good business?

Lots of things, of course. But one of the key factors is to provide a product or service that customers want to buy, without having to spend much money in doing so. This allows a business to make good returns on investment.

Ocado (OCDO) seems to be getting the first part right – the provision of a service. The second part – doing it cheaply – is not so easy.

And this is why its shares are getting hammered today. If Ocado doesn’t start turning its sales into profits soon, then the current share price may still be very expensive.

Let’s start with the positives. Ocado has nearly 40,000 more active customers than it did six months ago, as more households want to do more of their shopping with them over the internet.

Ocado is growing the range of products that it sells, and its own-label produce is selling well. The number of customer orders per week is growing nicely, and sales have grown by 11.4%.

But that’s where the good news pretty much ends. Despite throwing £2m more than a year ago at marketing vouchers, Ocado’s rate of sales growth is slowing down.

Sure, the economy is not helping matters and the UK grocery market is pretty competitive right now, but Sainsbury’s and Waitrose.com are growing faster. And Sainsbury’s growth is coming off a higher sales base than Ocado’s.

Ocado sales growth

What’s more disturbing is that this growth in sales is not feeding through into profits. I made this point when I wrote about Ocado a few months ago.

You see, the whole point of the Ocado investment story is that selling more goods spread over a large fixed cost base should see profits grow quickly. This is not happening.

Let me explain what I mean. What we should be seeing as the business matures is profits growing faster than sales. Costs should not grow as fast as sales. Therefore, we should see rising profit margins.

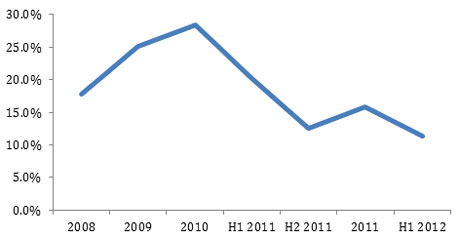

Ocado incremental profit margins

Ocado doesn’t have much profit, so I’ve compared the change in profit before depreciation costs (or EBITDA – although believe me, depreciation is a real cost with lots of delivery vans and warehouses) with the change in sales.

As you can see, Ocado was quite successful in improving its margins from extra sales from 2009 until the first half of last year. Since then things have not been too good.

To get more sales it seems to have to keep adding costs. In fact, during the last year, Ocado has made a trading profit (after depreciation) of just under £700,000 on sales of £629 million.

Are things going to get any better? It doesn’t seem likely. The company is due to open a second big customer fulfillment centre (CFC) early next year, which will add another layer of costs.

Given that it isn’t making any money out of its existing assets, could we see Ocado making losses again when costs go up next year?

That in turn raises the question, can Ocado’s business model work? Can it please customers and shareholders at the same time? I’m not sure it can.

Ocado is sinking more and more money into its business. By my calculations, it has invested £245m. If I were running a business with this amount invested, I would want a return on my money of at least 10% before tax to think it was worthwhile taking the risk. That means, I would want sustainable operating profits of at least £24.5m (£245m x 10%).

Ocado money invested (£m)

To be fair to Ocado, a large chunk of the money is invested in the second CFC which has yet to open. But at the moment, £24-£25m of operating profits looks a long shot.

And then comes the most interesting thing about Ocado – how much the stockmarket thinks it is worth. At 91p per share and 522.4 million shares in issue, its equity is worth £475m. Add on £71m of net debt and you would have to pay £546m for the whole business today – more than twice the amount of money invested.

Given that Ocado is a long way from making the profits needed to justify the money it has spent, I’m not sure why it is worth more than twice that. If someone were to offer you that amount to buy Ocado from you, it would look like good sense to sell. But if you were looking to buy, you’d be sensible to pay no more than £245m for the whole business and probably a lot less.

What I’m saying is that Ocado’s shares still look very expensive for a business that is yet to make meaningful profits. Yes, more people are buying their groceries over the internet, but no company has yet to make big profits from this trend.

Perhaps the real lesson for investors here is not to buy IPOs. Like most of them, it is the sellers of the shares that get the most value at the expense of the buyer. Ocado looks like a painful example of this, that could just get worse.