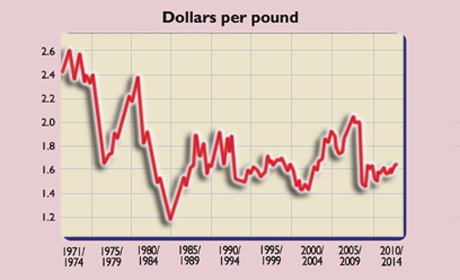

The pound started 2013 on a high – literally. On 1 January, sterling bought you nearly $1.64. Now it buys less than $1.58. It’s also fallen to its lowest level in more than a year against the euro. As Jane Foley at Rabobank told The Guardian, “for sterling these are big moves”. And it looks like this is just the start.

What’s the problem with the pound? Kit Juckes of Société Générale puts it down to three main factors. Firstly, the most recent set of economic growth figures were awful. GDP shrunk by 0.3% in the last quarter of 2012. Another set like that and we’ll have ‘triple-dip recession’ headlines everywhere.

There’s plenty of speculation over whether the GDP figure is reliable or not. And we’re hardly the only country to have struggled in recent years. But it’s increasingly clear that Britain has had one of the world’s weakest, indeed, nigh-on non-existent, recoveries from the financial crisis.

Weak data are bad for the pound because it means the Bank of England is more likely to do more money-printing via quantitative easing (QE). That takes us to the second factor weighing heavily on sterling: the prospect of a new central bank head who is even more aggressive about promoting growth – current Bank of Canada governor, Mark Carney.

In various speeches, Carney has suggested that he cares more about boosting growth than tackling inflation. That might not seem a worry, were it not that British inflation is already well above target at 2.7% (and even higher by the old retail prices index measure). A weaker pound will only make this worse.

Juckes adds a third factor: David Cameron’s threat to leave the European Union. “The UK is a small, open economy that has benefited from capital inflows because it is not in the euro area but is in the EU.” The former factor is having less impact now because investors have become less concerned about a eurozone break-up (you might argue that they’ve become complacent – as we’ll see in a moment).

As fears recede that one or more eurozone countries might drop out and return to their old currencies – destroying savings in the process – the pound is losing its ‘safe haven’ status, as Europeans no longer rush to shift their money out of the worst-hit nations. Meanwhile, the uncertainty over the EU vote leaves Britain’s position unclear. Britain may well carve out a better deal for itself, but no one knows at the moment.

More important than any of this is the fact that by now the coalition government, and the Conservatives in particular, must have realised that Britain may be facing a ‘lost decade’ rather than just a nasty recession. As a result, under their current plans, the chances of a feel-good recovery arriving in time to boost re-election prospects seem non-existent.

Unless the party wants to be out of power “for a generation”, as current Bank of England governor Sir Mervyn King warned before the 2010 election, then the Tories will have to try to boost growth by any means possible. Hence the appointment of Carney and the renewed zeal for high-speed rail links and infrastructure projects in general.

There’s also been a lot less talk from the government about the importance of Britain’s AAA-credit rating, which is just as well, because we’re very likely to lose it this year. All three main credit-rating agencies have Britain’s outlook on ‘negative’, which means they’re warming up for downgrades.

Despite all the talk of ‘austerity’, government spending is still rising. It’s stunning just how few people understand this: a poll last month showed that as little as 16% of British people realise the national debt is rising, notes Fraser Nelson on The Spectator’s blog.

Yet as Peter Hoskin points out on the Conservative Home blog, the national debt has already risen by more than 40% since the government came to power, from £786.4bn to more than £1,110bn. The government’s plan has always been merely to reduce the deficit (our annual overspend, rather than the overall debt pile). And even that’s not going very well.

In December, public-sector borrowing rose to £15.4bn from £14.8bn the year before, because spending still grew faster than income as the economy struggled. As The Daily Telegraph notes, borrowing this financial year could “hit around £130.5bn, £10bn above the government’s target of £119.9bn”.

It’s easy to dismiss the ratings agencies as merely the incompetent enablers of the sub-prime crisis (which they were). And neither the US nor France have suffered unduly for losing their badges of approval. But the danger is that Britain might not be able to shrug off its loss of AAA status so easily. For one, it would show clearly that the government’s plans aren’t working. For another, as Nils Pratley points out in The Guardian, “we’re not the US, after all”.

In short, Britain is over-indebted, desperate for growth, and increasingly willing to take drastic measures to achieve it. That’s a nasty recipe for the pound and sterling investors in general. So which currencies should you diversify into?

The yen

Let’s start with the nation most responsible for the latest batch of ‘currency war’ headlines: Japan. New prime minister Shinzo Abe was elected with a landslide at the end of last year. One of his aims is finally to jerk Japan out of its deflationary slump. And people are taking him seriously.

The Japanese currency spent most of 2012 hovering near an all-time low of around 77 yen to the dollar. Then Abe took over. He has pushed the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to embrace a 2% inflation target, and to commit to unlimited QE from next year.

Meanwhile, he and his colleagues have talked the yen down at every opportunity. A dollar will now buy you 90 yen, and many analysts think 100 is on the cards. The Japanese currency has also slumped against the euro.

There are, of course, still many sceptics unconvinced of the rally. Japan has disappointed so often in the past that this is understandable. However, Abe has the chance to consolidate his control over the BoJ within the next few months, when he appoints a new BoJ governor.

Assuming that the government is serious about weakening the currency – and it certainly seems this is a genuine change, not just bluffing – we believe the yen will continue to weaken.

However, this doesn’t mean you should avoid yen-denominated assets. As regular readers will know, we’re big fans of Japanese stocks, and a weaker yen is just the catalyst they need. The Nikkei and Topix indices have soared already, but they could have much further to go.

We’ve suggested in the past that you don’t worry about hedging your exposure to the yen, mainly because if this turns out to be another false dawn, you’ll be partly compensated for falling stockmarkets by a strengthening yen.

We still think this is a good idea, but we’ve also suggested some funds that hedge out the currency risk (in other words, which get the full benefit from any rise in the market) below for those who want to make a more aggressive bet.

Verdict: expect the yen to weaken, against the dollar in particular. But watch out for government ministers, manufacturing executives or central-bankers worrying about the rate of decline. If there’s a hint the government might stop backing the decline, a sharp correction could be on the cards.

The yen is also traditionally a ‘risk-off’ currency (it strengthens when investors panic). But the dollar is also likely to benefit from any ‘rush to safety’, so we’d still expect the yen to weaken against the US currency in this scenario.

The euro

The euro was a hedge-fund killer last year. Put simply, hedge funds expected the euro to shatter, and it didn’t. Now the currency just keeps getting stronger. There’s a good reason for this: the euro has refused to join the race to the bottom. It’s one of the few non-combatants in the currency wars, which means, of course, that it is squarely in the firing line: as other countries devalue, it will get stronger almost by default.

But wait a minute, you ask. Didn’t European Central Bank (ECB) governor Mario Draghi promise to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro? Indeed he did. Draghi effectively promised to print money to buy the bonds of troubled countries if necessary under the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) scheme. But it hasn’t been activated yet. The mere threat has been enough.

According to German market research group Sentix, last July, 73% of investors thought the eurozone would shed at least one country within the next 12 months. Now it’s just 17.2%. As Brewin Dolphin point out, “The OMT programme is a combination of stick and carrot which pressures governments to implement competitiveness reforms. By doing so, the scheme becomes not just a monetary policy but a supply-side policy. This demonstrates extraordinary reach for central-bank policy… the OMT has applied huge stimulus without actually doing anything.”

In short, investors are convinced the ECB isn’t bluffing. That’s kept eurozone bond yields down, and reduced the pressure on countries to leave. In other words, Draghi has bought time. And so far, there’s been little reason for him to try to talk the euro’s value down. After all, he spent most of last year trying to save it, and euro strength is a key barometer of confidence in the currency’s ability to stick together.

On top of that, as Richard Barley at The Wall Street Journal notes, banks have recently repaid €137bn ($184.3bn) in long-term loans to the ECB. This means its balance sheet has actually shrunk, rather than expanded. For now at least, “the ECB looks like the only traditional inflation hawk in town”.

So pile into the euro then? Not so fast. Whatever you think of the European project, Draghi is without doubt a master diplomat, politician and central banker, who no doubt deserves all the plaudits heaped on his head last year. But he’s not a miracle worker. As one analyst put it, the big question is: “how long can the EU really keep getting away with one fine sentiment from Draghi?”

That brings us back to the fundamental problem at the heart of the eurozone. Different countries need different monetary policies and different exchange rates. The stronger the euro gets, the more damage it does to the weakest economies. For example, Deutsche Bank reckons that, due to their lack of competitiveness, a more reasonable rate would be $1.22 for France and $1.16 for Italy, says Barley.

So, sooner or later, the current exchange rate is going to hurt. European leaders have already expressed concerns about Japan’s decision to weaken the yen. Sooner or later, Draghi’s credibility – and Germany’s willingness to accept money-printing – will be put to the test.

“There is no ‘Goldilocks scenario’ for the euro,” as John J Hardy at Saxo Bank puts it. One way or another, the weaker countries “must be allowed to devalue”. So, as far as Hardy is concerned, either the ECB will end up having to do QE (which will, of course, weaken the euro), or “we see a spike in euro strength leading to an EU break-up”.

So we’d agree that the euro is likely to run into trouble again in 2013, and the stronger it gets, the more likely that becomes. However, as with Japan, we still like European stocks. European markets have recovered from their lows of last summer, which is when we told you to start buying, but there is still room for further gains – and if the ECB is eventually forced to print, it could send stocks even higher.

Verdict: the trend for the euro is higher just now, but we expect that to turn at some point later this year, once markets put Draghi’s credibility to the test. Deteriorating economic data could be the catalyst, while other major potential political flashpoints include discussions over a bail-out for Cyprus, the Italian elections in February and the lead up to the German elections in autumn.

The US dollar

Back in July 2011, we ran a cover story suggesting that the US dollar was about to return from the dead. A few months earlier, in May 2011, the US dollar index (DXY), which measures the performance of the dollar against a basket of other major currencies, had hit a near-record low of around 73. Since then it has gradually trudged higher. But what’s next?

A lot boils down to what the Federal Reserve has planned – and what investors expect from it. Some analysts argue that the Fed is on the verge of abandoning QE. The American economy, while heavily indebted, is undoubtedly in better shape than both the British and European economies.

Its banks are in better condition. Its housing market has almost certainly bottomed out – it might not rocket in value again, but it’s not overhanging the economy, unlike the British housing market. The American economy is actually growing, unlike Britain, Japan and much of Europe.

And, of course, the discovery of a very cheap source of energy in the form of shale gas is working wonders for its trade balance, massively reducing the amount of energy the country needs to import.

On top of that, America is simply bigger than everyone else. When investors are frightened, the dollar is a natural homefor their money. But with the underlying US economy now strengthening, the dollar also looks attractive relative to much of the rest of the developed world. So the dollar could benefit both from ‘risk-off’ (fearful) and ‘risk-on’ (greedy) mode.

While the likes of Switzerland and even Japan can draw a line in the sand, and explicitly say that they won’t allow their currencies to appreciate any further, it’d be a lot harder politically for America to do the same. Especially given that the dollar remains extremely weak compared to its own history (since 1967, the DXY’s average level has been around 98, so the current level of about 80 is still pretty puny – see the chart below).

Set against all this is one simple fact, says Martin Spring in his On Target newsletter. While some Fed members clearly sympathise with the view that QE should end sooner rather than later, as Asia-based strategist Christopher Wood points out: “The only three Fed governors that matter” are the chairman, Ben Bernanke, his deputy Janet Yellen and New York Fed president William Dudley, and “they are all in the super-dovish camp”.

In other words, the Fed will try to keep monetary policy as slack as it can for as long as it can justify it. Bernanke’s tolerance of a strengthening dollar may only go so far. Of all the world’s central bankers, he has easily proved himself the most experimental, and the one willing to go furthest in the quest for growth.

So our overall view would be to expect the dollar gradually to get stronger, but expect regular run-ups and setbacks as the Fed turns out to be more dovish than investors anticipate. But as a sterling investor, how do you play a stronger dollar?

As we’ve noted several times in the past, while we find some areas of the market interesting – dare we say it, some US banks might now be the most attractive play on the recovering housing market – we’re reluctant to buy the US market as a whole, because it’s pretty expensive compared to history.

Instead, we think you’d be better off buying big multinationals who make a decent amount of their earnings in the US. We look at some candidates below.

Verdict: The American dollar is hardly a model currency. However, of the major alternatives, it is probably the ‘least worst’. We’d expect it to strengthen this year.

But what are the risks? If American economic data – and employment data in particular – get weaker, the Fed will have an excuse to keep monetary policy looser for longer. If employment improves more rapidly than expected and inflation starts to pick up, the Fed will have to shift the goalposts even further if it wants to maintain QE and zero interest rates, and even that might not prevent markets from pushing the dollar higher in expectation of eventual tightening.

The commodity currencies

The key commodity currencies – those that share in the fortunes of their resource-rich countries – are the Australian dollar (the Aussie), the Canadian dollar (the Loonie), and the New Zealand dollar (the Kiwi). Even though markets have been in a risk-hungry mood for the last few months, the Aussie has seen little movement and has even drifted lower. There are good reasons for this.

For one thing, even those investors who believe in China’s rebound realise that the country has to move away from its dependence on infrastructure building if it is to have a hope of continuing to keep its population happy and maintain its economic growth. That means demand for commodities and base metals in particular is going to fall.

Moreover, as John Hardy of Saxo Bank points out, “the vast majority of Australian sovereign debt is in foreign hands, and the country has an enormous accumulated current-account deficit” (this is a problem for New Zealand too). “Any move that spooks foreign investors could spell significant downside and volatility.”

As for Canada – it’s probably in a better position than Australia, partly due to its proximity to America. However, for all that central-bank head Mark Carney has achieved near-mythical status in Britain already, he’ll be leaving behind a country with a huge housing bubble and massive consumer debt.

The nation is set to suffer “an ugly hangover”, reckons Hardy. In short, we’d expect the Aussie to fall against the US dollar this year, and we wouldn’t expect the Canadian dollar to perform brilliantly either.

Beware ‘safe’ havens

What about the likes of the Swiss franc and the Scandinavian currencies? These currencies are backed by attractive economies and are often seen as safe havens. However, we’d be careful.

There’s nothing wrong with adding a bit of diversification to your portfolio by having some of your money invested in these countries. But don’t bet on these safe havens staying safe. These countries don’t like being the patsies who have to deal with the fall-out from the currency wars.

As Pimco’s Mohammed el-Erian points out, “strong currencies carry potentially significant costs in terms of hollowing out industrial and service sectors”. We’ve already seen the Swiss make the decision to peg their currency to the euro at 1.20 Swiss francs to the euro.

The Norwegian central bank has expressed concern about the impact of the krone’s strength too. Beyond fear of inflation – which these days seems to worry very few people outside of Germany – there’s little to stop these nations from retaliating by hammering their own currencies.

As Gary Shilling notes on Bloomberg: “Decreasing the value of a currency is much easier than supporting it. When a country wants to depress its own currency, it can create and sell unlimited quantities. In contrast, if it wants to support its own money, it needs to sell the limited quantities of other currencies it holds or borrow from other central banks.”

How to profit from currency trends

If you want to play currencies directly, the easiest way is to use spread betting. But before you do so, understand that spread betting on currencies is speculation, rather than investment. You’re doing it over the short term, you’re betting on the direction of the market rather than buying for an income stream, and you can lose an awful lot of money (spread betting is very risky).

If you’re interested, then sign up for our free email, MoneyWeek Trader, which looks at tricks and tactics that will enable you to run your profits and cut your losses.

If you are more interested in diversifying your portfolio to protect yourself from sterling weakness and profit from other major currency trends, we’d suggest holding a range of assets.

To make money from Japan’s determination to shake deflation, we’d buy Japanese stocks. One of our favourite Japanese investment trusts, the Baillie Gifford Japan Trust (LSE: BGFD) has done nicely for sterling investors since November.

If you’d rather hedge your yen exposure, you could try iShares MSCI Japan Monthly GBP Hedged (LSE: IJPH). It has a total expense ratio of 0.64% and is up around 30% since November. Another partly hedged option if you like unit trusts is the Neptune Japan Opportunities fund.

On Europe, we still believe that, while markets may stop for a breather at some point, they have further to rally, because they are still cheap on a long-term historical basis. The Italian exchange-traded fund iShares FTSE MIB (LSE: IMIB) is up by more than 30% since we tipped it in June, but we’d hold on to it (disclosure: I own this ETF).

As for the dollar exposure – several FTSE 100 stocks, such as the pharma giants, make more of their revenues in dollars than in sterling. Alternatively, opt for one of our favourite investment trusts, the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (LSE: SMT), which invests globally, with a heavy weighting to both North America and continental Europe.