“The world is used to a weak dollar but the signs are it is going to have to adapt to a strong dollar going forward,” says Clem Chambers on Forbes.com. The gradual economic recovery in the US will lead to rising interest rates, encouraging capital that has flowed elsewhere in a search for yield to return home, thereby buoying the greenback.

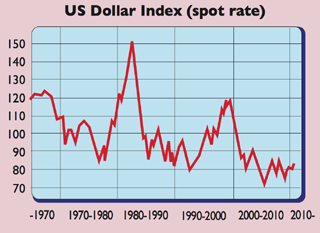

The trigger for this shift will be the wind-down of quantitative easing (QE), says David Woo of Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Once QE ends and interest rates begin to normalise, expect the US dollar index – which measures the weighted average value of the dollar against a basket of major currencies – to rise sharply. A quick return to 100 – the average level over the past 35 years – is likely, he thinks. (A higher value for the index indicates a stronger dollar.)

Such a view is becoming the consensus and it’s difficult to find any analysts with a firmly negative view on the dollar at present. To contrarians, that may be a warning signal: a strong rise is no certainty, at least in the near term. Nonetheless, the dollar has a clear history of alternating between multi-year uptrends and downtrends, with good fundamental reasons for this, says Binky Chadha of Deutsche Bank (DB).

Its status as the world’s reserve currency creates a complex interaction between capital flows, economic competitiveness and interest-rate cycles that encourage it to swing from overvaluation to undervaluation and back again over long periods.

During the last decade, the dollar seems to have followed a steady downtrend to undervaluation and the economic and monetary conditions for that to reverse into a strong dollar cycle now appear to be in place. So, if the dollar is likely to head higher sooner or later, who will be the winners? The effects are not straightforward. For example, a strong dollar is usually reckoned to weigh on commodity prices – but if it results from a stronger US economy, the increased demand would be positive for commodities, argues Sudakshina Unnikrishnan at Barclays.

Past history also suggests that US equities usually outperform emerging markets (EMs) during an up cycle – but at present, US stock valuations seem stretched relative to EMs. Perhaps the most straightforward effect is that firms with low US dollar costs relative to revenues will benefit from improving margins. That should disproportionately benefit Japanese and European exporters over many of their US-based peers, says DB’s Chadha.