Both Corbyn and May are trotting out failed economic ideas from the 1970s. The UK must avoid repeating those mistakes, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

Earlier this week, I rummaged around in the back of my cupboards and pulled out my old maroon corduroy jacket. It seems that after some while in the wilderness, it is back on trend. This, says The Sunday Times, has nothing to do with the “ageing army of British geography teachers still wearing trousers they picked up in M&S in 1973” and everything to do with high fashion. It is “smart casual in the best possible way”. It is “non-intimidating and easy to wear”. It inspires “preppy nostalgia”. And in its new incarnation it’s really expensive: Mulberry has a dusty pink cord skirt for £450 and Gucci will sell you a floral cord jacket for £1,610. It is also not the only thing that we had thought properly buried in the 1970s that is making a disturbing comeback. Think political instability; the kind of high taxation that destroys the capitalist incentive; high levels of union power; nasty inflation; and a belief that governments should not just facilitate, but actively direct economic policy.

The 1970s began with the unexpected election of conservative Edward Heath (something that was as much of a surprise to Harold Wilson as the loss of her majority was to Theresa May) – and went firmly downhill from there. Heath almost immediately abandoned any ideas of arresting the UK’s economic decline through free market capitalism. Instead, he doubled down on the corporatism of the time. When things went wrong he bailed firms out or nationalised them, he bumped up public spending to increase demand and keep unemployment under control, and he put in place all sorts of hopeless income policies to cap inflation. None of this worked for him particularly well. By the time he was eventually forced from office – after an early election triggered by the miners’ strike and the consequent three-day week, a loss of his majority, and an unsuccessful attempt to form a coalition with the Liberal Party (that’s history rhyming for you) – Heath had declared five separate states of emergency. This wasn’t all his fault, of course. The entire Western world was reeling from the collapse of Bretton Woods and the 1973 oil crisis. The UK – where GDP fell by more than 3% between 1973 and 1975 – was hardly the only country in trouble.

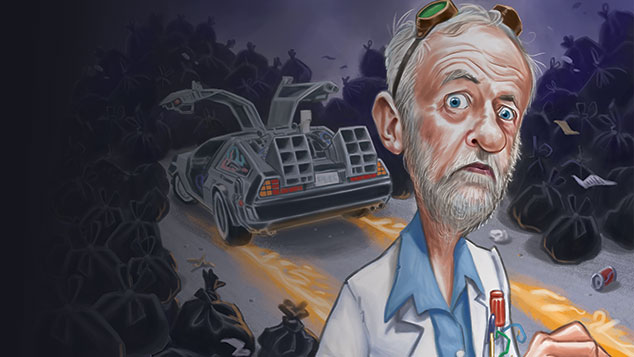

But nonetheless, Heath’s lurch from crisis to crisis set the scene for the decade – one of bad policy, bad luck and general grimness. I have a pile of 1970s revisionist history books on my desk at the moment. They all set out to explain why it really wasn’t that bad after all. But while they are all convincing on the fun in fashion and culture, none can actually revise away the Winter of Discontent – in which schools closed, the streets filled with rubbish and the dead went unburied. None can claim that the state’s attempts to direct the economy via the National Economic Development Council (known as “Neddy”) were much good. Let’s not forget that one of the decade’s defining government investments was the £54m it gave to John DeLorean to build his stunningly unsuccessful car. None can imagine away inflation at 20%; the secondary banking crisis (driven by a collapse in UK house prices); the 73% fall in the FT30 in 1973/1974; the miseries of 1,500,000 unemployed (there was no tax credit system to help out); the crisis of confidence evident in the endless elections (Heath was replaced by Wilson, who resigned for James Callaghan, who was pushed out by a vote of no confidence put forward by Margaret Thatcher), the rescue by the International Monetary Fund; or the antagonism between different economic stakeholders.

“Think political instability; high taxation; high levels of union power; inflation; and a belief that governments should not just facilitate, but actively direct economic policy”

So, the odd bit of cord aside, no one should actually want to go back to the 1970s. In the years since, the UK has become something entirely different. Thatcher’s revolution made us one of the most open, business-friendly countries in the world. The UK is the biggest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe, notes Bagehot in The Economist; it has the world’s most liberal corporate takeover rules and comes number seven in the World Bank’s ease of doing business index. Unemployment is extraordinarily low at 4.4%; and big companies are still piling in. Google is building a campus for 5,000 employees in King’s Cross. Nissan is increasing its UK production by 20% and doubling the volume of components it buys here. Manufacturing orders are at their highest level since 1988. Wells Fargo has just spent £300m on a new European headquarters in London and while some banks have said they will be moving some staff to locations inside the European Union, it is striking, says Omar Ali, UK Financial Services Leader at EY, “that the majority of firms are maintaining their commitment to the UK”. This is something that suggests that the UK’s financial ecosystem really is “very hard to replicate in other European jurisdictions”.

At first glance, that’s not bad. But the UK is not exactly perfect. We continue to run a nasty budget deficit; wealth inequality has been growing largely thanks to quantitative easing and super low interest rates (see page 13); average real wages have been falling; and our dysfunctional housing market has spread its poison throughout the economy. With this in the background, it makes perfect sense for 1970s-style disagreements to rise up again. Have we let the power pendulum swing too far since the disasters of Heath, Wilson and Callaghan? Are big companies too powerful? Are workers too weak? Is wealth in the UK fairly distributed? Have we let the financial sector destroy the real economy? And what should the government do about it?

The consensus answers to these questions today are likely to be the opposite to Thatcher’s answers in the early 1980s: yes, yes, yes, no, yes and something. The key thing to look at here is how economic power was distributed then, how it is distributed now, and how it might change. In the 1970s, the UK saw very high wage growth and fast inflation despite the fact that unemployment was high and the economy was entirely stagnant. Why? Because thanks to the strength of the unions, economic power was rather more evenly distributed than today. “Workers and bosses, creditors and debtors, fought one another for a larger slice of the pie,” says Felix Martin in the Financial Times. Their negotiations tended to fail. So “the path of least resistance was the excessive expansion of credit”, so that everyone ended up with the illusion of having what they wanted. That gave us inflation – society’s “default mechanism of reconciling” competing financial demands.

“Over the last 35 years, globalisation and technology have changed the power balance – bosses have long won pretty much every pay battle anyone has begun, for example”

Over the last 35 years, globalisation and technology have changed that power balance – bosses have long won pretty much every pay battle anyone has begun, for example. At the same time, in the 1970s, the man in the street with a strong trade union wasn’t bothered by inflation (his wages rose to match) and the voice of the elderly living on fixed pensions was barely heard. Today, ageing baby-boomers, keen to hang on to their retirement benefits, state and private, have used their votes to encourage monetary looseness and fiscal austerity, the effects of which hit the young rather more than the old. These are the two most important dynamics to watch over the next decade: all investors should be considering what happens when power shifts back, from boss to worker, and from old to young – as it looks like it is beginning to.

Theresa May has consistently railed against the “unacceptable face of capitalism”. While she isn’t exactly as strong as she hoped to be, her government is still having a go at finding a way to regulate executive pay (I think she is doing it wrong – see the box on page 20 – but it does represent action). Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has similar if stronger proposals: under his plans, only companies that give full recognition to unions, comply with collective bargaining agreements and have a 20-1 pay ratio, would be eligible for public procurement contracts in his government. Both leaders are clearly hearing the message from workers. Corbyn is also hearing the message from the young – note his plans to drop tuition fees. Both also realise that their jobs will be significantly easier if they can head off some of the political struggle ahead by showing willing to put up public money in an effort to avoid GDP stagnation.

Unfortunately they are both also looking to the 1970s to see how. Adam Smith’s idea that “little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice” cuts no ice with either party leader. May has resurrected the idea that for the UK to grow in a way that “works for everyone”, it needs an industrial strategy. Her “winners list” includes the five sectors her government wants to help the most: life sciences, industrial digitalisation, low-emission vehicles, nuclear and the creative industries. Corbyn’s very keen on this too. His party reckons that May’s ideas are “small scale and ad hoc, industrial strategy without the strategy”. His version involves an awful lot of destructively expensive renationalisation (rail, mail and energy) and significant economic direction in a very 1970s way: note that in his leadership election campaign he praised James Callaghan’s government for industrial strategy.

“Under Corbyn’s plans, only companies that give full recognition to unions, comply with collective bargaining agreements, and have a 20-1 pay ratio would be eligible for public procurement contracts”

Some of this might work (although the lessons of the past suggest it won’t, as Picking Losers, a 1983 pamphlet on the topic from the Institute of Economic Affairs, explains). But whether the state manages to pick the odd winner or takes the usual route to picking losers (politicians and bureaucrats rarely have much in the way of “entrepreneurial acumen and managerial expertise”, notes the IEA), all this industrial support comes at a high cost. John Bell, the Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University, released a report on the first of May’s winners – the life sciences sector – this week. It suggests the UK taxpayer be obliged to help finance “large research infrastructure projects and high-risk “moon shot” programmes that will help create entirely new industries in healthcare”. Each is to cost several hundred million pounds. That’s real money.

There is clearly a huge difference between May and Corbyn. The UK will be in a lot more economic trouble if it elects him rather than sticking with her. History is full of extremists who pull back on their more nonsensical ideas when they attain power, says The Economist. But should Corbyn get in, he is unlikely to be one of them – he has, after all, been banging the same drum for 40 years. However, whoever takes Britain through the next ten years, there is little doubt that there is a power shift taking place – one that investors need to prepare for. It is likely to bring more rounds of aggressive political struggle within a 1970s-style two-party state in which no one has a clear majority (the SNP and Lib Dems are irrelevant again); growing state interference in all things corporate; new taxes on wealth (however much the baby-boomers resist); higher wages; and – the thing investors should worry about the most – rising inflation.

Three lessons from the 1970s

On 1 May 1972 the FTSE All Share index stood at 228.1. By 13 December 1974, it had fallen to 61.92 – a slide of 73%. In hindsight, it is easy to see what went wrong. The market stayed pretty flat through 1972, but as industrial disputes kicked off, pay guidelines were breached by the miners and railwaymen and inflation soared, confidence and hence trading volumes fell sharply.

Then came the sterling crisis (in which the UK discovered that international currency markets don’t much fancy inflation) and a five-week dock strike. This was fast followed by the collapse of pay talks between the government and then a counter-inflation bill that gave the government power to regulate prices, pay, dividends and rent for three years. That was the last straw. The All Share fell 3.3% in one day – and continued lower for two years. It then took off again (rising 188% between 1975 and 1976); fell again (down 32% from May to October 1976); and rose again (up 144% by May 1979).

The lessons? First, there are times when investors find favour with neither political party. No one took up the cause of the widows living on dividends. Second, markets can take a while to react to political change. But when they react, they really react. Best be out first. Third, one reason to invest in equities is to protect against inflation. But when inflation really takes off, even the most carefully constructed portfolios can only partially mitigate the effect. The good news? It is an awful lot easier to diversify both abroad and across asset classes than it used to be. Investors keeping an eye on the UK’s shifting sands of power might like to make sure they do just that.

It’s not the state’s business to set pay

Who thinks it reasonable that Peter Crook, ex-boss of Provident Financial and overseer of the strategy that has destroyed its business, has been paid a total of around £40m over the last decade? Probably no one. But he is hardly alone in the UK in being fabulously overpaid: getting a gig at the top of one of our big companies has become a surefire way to make a proper fortune – often at the expense of an awful lot of other people.

So what should be done? Theresa May’s watered-down plans were made public this week. They are pretty feeble. Nine hundred listed companies will have to publish the ratio of their CEO’s pay to that of an average member of staff. They will also have to put a worker representative on their boards – a non-executive who represents staff, an actual worker or an employee advisory council – or explain why they have not done so. And a public register of listed firms where more than 20% of shareholders vote down executive pay deals is to be created.

Some think that even these minor measures go too far – making the perfectly reasonable argument that it is not the business of government how much any particular executive is paid. I would say that they do the wrong thing. It is not the business of the state to set pay. But it is the business of the owners of each company. May should have put forward changes that give shareholders annual binding votes on how much the people who work for them get paid. Crook might not have liked that much. But Provident Financial might have been the better for it.