This article is taken from our FREE daily investment email Money Morning.

Every day, MoneyWeek’s executive editor John Stepek and guest contributors explain how current economic and political developments are affecting the markets and your wealth, and give you pointers on how you can profit.

.

Just before I get started this morning – don’t miss MoneyWeek’s Isa special, out tomorrow. If you’re not already a subscriber, sign up now.

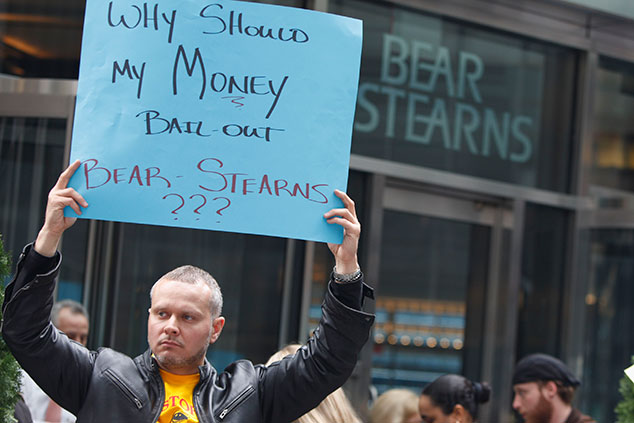

It’s now been ten years since Bear Stearns was bailed out by the US Federal Reserve.

Northern Rock had gone down a few months before. Markets could broadly shrug off the demise of local building society.

But the collapse of the scrappy US investment bank signalled that something was going badly wrong with the financial plumbing.

A year later, central banks weren’t just bailing out one bank – they were bailing out the entire global financial system, with unprecedented interventions, from cutting interest rates to near-0%, to quantitative easing (QE – printing money).

And it’s only now that we’re starting to reflect on the massive consequences stemming from the choices made under pressure back then.

How global prime property markets became synchronised

There’s an excellent piece in the FT today about how and why prime house prices in major global cities have shot up so strikingly – and in unison – since the financial crisis.

The writer, Nathan Brooker, cites Yolande Barnes from upmarket estate agency Savills. “Looking back, we didn’t quite understand what QE would do globally… for the first time, the cost of money in most of the cities was similar – you might say quantitative easing levelled the global playing field.”

A desire for “safe assets” drove the super-rich to snap up properties in prime markets. Trouble is, notes Brooker, that this results in the housing market in prime cities becoming “increasingly hostile to its own citizens.”

Brooker’s piece talks about how this has led to a glut of high-end luxury properties in many cities that now can’t be shifted, because they’ve simply become too expensive, even for wealthy plutocrats.

In short, the outlook isn’t good.

Globalisation and its discontents

But there’s one major point that isn’t highlighted in the FT piece: this synchronisation of global urban property markets is a globalisation story as well as a QE story.

After all, you can only buy properties in other countries when you have the sort of freedom of movement for capital (and individuals) that we have today.

Before the 1990s, a lot of that capital (and those individuals) were stuck behind an Iron or Bamboo Curtain. And even that was not the case, countries in general have become far more open and connected than they once were.

But the people who can make the most use of that mobility are the super-rich. Combine that with the additional leverage of QE, and you have a recipe for soaring asset prices and soaring discontent.

My colleague Merryn highlighted an IMF Working Paper on this topic on Twitter the other day. The paper – The Distribution of Gains from Globalisation, by Valentin F Lang and Marina Mendes Tavares – looks at the impact of globalisation on incomes.

Cut a long story short, globalisation is good news for “countries at early and medium stages of the globalisation process”. In other words, opening up to trade and the rest of it is good for countries overall and makes them wealthier.

Trouble is, after a certain point, the gains become “insignificant”. And “within countries, these gains are concentrated at the top of national income distributions, resulting in rising inequality”.

In short, the good bits of globalisation accumulate over time to those who are already better off than everyone else. The paper doesn’t say anything about who gets lumped with the bad bits of globalisation (intense low-skilled labour competition, for starters). But you can guess.

The losers now outnumber the winners

Now, just to be clear, I am more “pro” than “anti” globalisation. It’s nice to be able to cross borders conveniently, and live in other countries. It’s nice to be able to invest across borders too.

But as well as winners, you create losers. Prior to the financial crisis, there were more winners than losers, so it could hold together. But the financial crisis tipped the balance.

A system that apparently worked to make everyone rich – largely through the mechanism of cheap credit for all, plus rising national house prices and falling consumer goods prices – collapsed. People felt shocked and betrayed.

The betrayal was then compounded by the fact that the actions taken to save the system – slashing interest rates and printing lots of money – largely accrued to the same people who apparently had broken the system in the first place.

The current political backlash is a direct result. And the current dividing lines – no longer right vs left, but elite/status quo vs populist/change – make this quite clear.

Put very simplistically, globalisation’s winners and the defenders of our existing systems, are aligned with the “elite”. Globalisation’s losers want their share, and they’re the ones backing the populists. And increasingly, they are in charge.

You can’t whisk a prime residence away in a hurry

That means that the policies that have led to soaring prime property prices are under threat.

You see, there are really only two ways to help globalisation’s losers out. One is to reverse globalisation; in the context of bigger picture economics, that means trade wars. And in the context of global property markets, it means banning rich foreigners – as we’re seeing in New Zealand, for example.

The second is to give the losers their share of globalisation’s riches by taking it away from the winners. Global income is tricky to tax (although governments are trying to do it – see the current consultation on taxing tech companies in the UK, for example), but static wealth is a lot easier. And you don’t get much more static than good old bricks’n’mortar.

That’s why the global rich are no longer interested in snapping up overpriced properties in central London, or in plenty of other places for that matter. Even if Jeremy Corbyn never wins power, successive Conservative administrations have made it ever-more expensive for foreigners to buy high-end properties.

From Great Recession to Great Rotation

There aren’t many investment recommendations that arise easily from this. It’s just worth recognising that both politics and economics are now stacking up against the “business as usual” scenario we’ve been immersed in since the rally in 2009.

That doesn’t mean we’re facing another financial crisis. It’s more that the old certainties are being shaken up. Yesterday’s winners will be tomorrow’s losers. Maybe we’re moving from the Great Recession to the Great Rotation.

We’ll explore all this in more detail as it unfolds. But I suspect, if nothing else, that high-end property is past its sell-by date.