How has the industry fared recently?

The first decade of this century was an unmitigated disaster for the music industry. Consumers got used to getting music for free via illicit digital file-sharing sites such as Napster, and the market for physical CDs collapsed (halving between 2000 and 2008). Nascent digital stores (such as iTunes) couldn’t make up the difference as they unbundled individual songs from albums. Between 1999 and 2014 the global music industry lost 40% of its revenue.

And now?

Things are looking decidedly perkier. In 2015, the market grew significantly for the first time since the late 1990s and it has kept expanding. Last year, global revenues (in the recorded music business) stood at £17.6bn (up 8.1% year-on-year) – its highest level since 2006, though still only two-thirds of the 1999 peak. The key to the recovery is the rise in streaming. Consumers are opting to “rent” music rather than buying it.

A monthly payment gives access to millions of songs from the likes of Sweden’s Spotify, Apple Music and Amazon Music via our smartphones. Music companies license their artists’ music to these streaming sites.

How much has streaming helped?

In 2017, revenue from streaming surpassed sales of physical music formats (CDs and the like) and downloads for the first time. Streaming was worth $6.6bn globally (a jump of 41%) and accounted for 38% of the market; physical formats comprised 30% ($5.2bn, a drop of 5.4%). UK record-label revenues grew faster than any year since 1995 (the height of Britpop and the Blur versus Oasis chart battles) with labels seeing a year-on-year rise of 10.6% to £839m (still lower than the UK’s 2001 peak of £1.2bn).

A hefty chunk of that rise was accounted for by a massive 45% jump in streaming revenue, from £239m in 2016 to £347m in 2017. The upshot? If the internet was bad for the music business, the smartphone has been a boon.

What else is new?

First, the three major global labels (Universal, Warner and Sony) have stabilised and are all preparing for a leaner, more flexible future. Universal has even just managed to sign up the pop world’s biggest star, Taylor Swift, in an indication that the era of the record label is not dead – though they did have to agree to let her retain ownership of all her master recordings and promise that if and when they sell their $1bn stake in Spotify, the proceeds will be handed to its artists.

Meanwhile, the demise of physical formats has led to a boom in live touring. It is so much more profitable for artists than recording that it has seen the artists’ slice of the overall industry pie rise from 7% in 2000 to 12% now. In other words, the “record industry” is only one, much less significant, player in a broader “music industry” in which the biggest players are live music businesses and tech firms.

Such as Spotify?

Indeed. It has taken time for streaming to establish itself. Artists were at first incredulous at the apparently derisory rates on offer. A survey earlier this year for Digital Music News suggested that Apple Music pays an average of $0.00783 per stream, and Spotify $0.00397. Big artists, including Radiohead’s Thom Yorke, Taylor Swift, Adele and Beyoncé, initially refused to let their labels license their material to streaming platforms. But as Spotify and other streaming services grew steadily along with the global market for smartphones, it became clear that all those pennies could add up to serious sums.

Who benefits most?

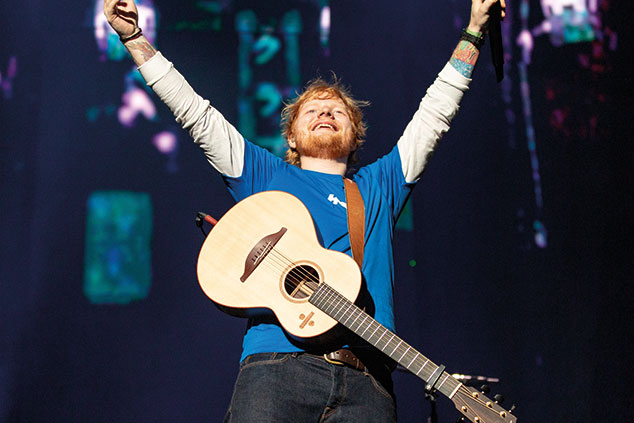

The biggest artists are making hay. According to Sam Wolfson in The Guardian, the very biggest stars, such as Ed Sheeran and Drake, have earned $50m from Spotify alone (which accounts for about 42% of the streaming market). Sheeran’s label, Warner, earned $1.3bn from streaming last year. And Sheeran, the unassuming Suffolk boy who became a global phenomenon, certainly knows how to monetise his content.

Spotify works on a system of playlists, offering different kinds of music to different fans. So, for his massive global hit Shape of You (a dancehall-influenced pop song), Sheeran also recorded and released an acoustic version, a reggaeton version for the Latin market, and four further dance remixes – adding up to a record two billion streams.

What about other artists?

Big acts whose careers predated the streaming era are also banking handy sums. Fleetwood Mac, for example, have around 11 million monthly listeners.

But the success of Spotify also means that artists in all kinds of niches who have a dedicated following, without achieving mass-market success, can also make a living. The singer-songwriter Jones, for instance, fills mid-sized London venues, but her debut album didn’t make the UK top 200.

Five years ago, that would have meant a short career. But she’s been streamed tens of millions of times on Spotify (meaning revenue in the tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds).

What’s the future for the music business?

For all Spotify’s success, it is not yet profitable, and there’s no obvious sign that this will change as long as it depends exclusively on others to license its content. Citi analysts predict that “renting” and live experiences will continue to grow in importance, and that the industry’s structure will evolve to reflect these changes in consumer behaviour.

Streaming firms will try to become more like a label by doing deals directly with emerging artists. And labels will become more like concert promoters by moving into live events. For artists, says Citi, these trends are likely to mean they “capture a larger share of the ecosystem’s revenues”.