The economy finally seems to be perking up. But only because it has had a hit of cheap money. Expect a comedown, says John Stepek.

Anyone reading the papers this week could be forgiven for feeling a strong sense of déjà vu. A government on the verge of another ‘humanitarian’ war in the Middle East. Soaring oil prices. The return of Foxton’s, London’s most aggressive estate agency, to the stock market. It’s like the mid-noughties never went away.

There’s a similar feeling to the economy. The new Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, seems to have timed his entrance to perfection. What was seen as a stuttering recovery at the start of the year has given way to ever-strengthening economic data. Britain’s second-quarter economic growth was recently revised up to 0.7%, from 0.6%, even stronger than anyone had expected. Growth improved in all areas, from investment spending to manufacturing to exports.

Employment data continue to perk up. Retail sales were stronger than expected in August, according to the Confederation of British Industry, with shops reporting the best growth since November 2012. And, of course, house prices are rising again – even beyond the hothouse of global investor demand that is London and southeast England. According to the latest data from Halifax, UK house prices rose at an annual rate of 4.6% in July, the fastest rate in nearly three years, helped by the government’s efforts to promote cheap lending to first-time buyers via the Help-to-Buy scheme.

Of course, it would be surprising if there had been no recovery at all. Britain was among the countries worst hit by the financial crisis, and it is true that our route out of this recession has taken far longer than is typical. But there’s no doubt about it. It might have got off to an anaemic start, but the data now point to a recovery, and given the steepness of the collapse that preceded it, the vigour of the rebound could well surprise us all.

The snag

There’s just one snag. And unfortunately, it’s a big one. We might be heading for a sharp cyclical recovery (and one you can take advantage of, as we note below), but when it fades – as it will – we’ll be left with even bigger problems than we realised. To understand why, you have to consider what Britain’s pre-crisis economy was built on. The one-word answer is ‘debt’. In the run-up to the crisis, interest rates – all around the world, but let’s focus on Britain – were kept too low for too long.

The credit boom artificially inflated everything from bank profits to tax revenues to British house prices. The government used the super-sized tax revenues from the City to fund a significant expansion of the state, while mortgage equity withdrawal and cheap credit helped to fuel rising household consumption. As Richard Jeffrey of Cazenove Capital Management notes: “The reason that the UK recession was so deep was that the household sector had previously got itself into dire financial straits – encouraged, it may be added, by a protracted period of below-normal interest rates.”

You’re probably starting to see exactly what the problem is. Just like the boom that preceded the crash, this recovery is based on debt too. Our central bank is taking great pains to explain that interest rates will be kept on hold for the forseeable future (more on this in a minute). And our government’s flagship economic policy is based not on making house prices more affordable, but on using taxpayer-backed funds to make it easier for people to borrow enough money to buy houses at their still-inflated values.

As Allister Heath argued in The Daily Telegraph recently, the economy is “drugged up on cheap money, subsidised credit and rock-bottom interest rates… Rather than this being a genuine recovery, we are merely entering the latest stage of an ongoing bubble that began at the start of the previous decade and which keeps being reflated, with the painful but inevitable denouement still at least another crisis away.”

How long can the recovery last?

We could go on and on about the things that really need to happen to create a sustainable recovery in the UK (a re-evaluation of the size and role of the state in the UK, and a serious discussion of how to fix Britain’s dysfunctional relationship with property would be good for starters), and you can read more on this in my report on the state of Britain.

But from an investment point of view, the big question for investors hoping to take advantage of the rebound is: how long can this recovery last before the “inevitable denouement”? Clearly, Chancellor George Osborne’s plan is to get the British economy running hot in time for the 2015 election. That’s why his focus has fallen on house prices, in particular. As Capital Economics has noted, the coalition’s poll ratings correlate directly with the rate of change in house prices – in short, rising prices equal more votes for the party in power. But while the strategy might be Osborne’s, the day-to-day management of it is in the hands of one man: Carney.

That’s because more than anything else, this recovery depends on interest rates remaining low. House prices at current levels cannot be sustained in the absence of low rates. As Cazenove’s Jeffrey puts it, what happens to buyers being drawn into the market now “when money costs start to rise, and fixed-rate agreements begin to lapse”? In short, there’s a good chance that this debt “will turn out to be extremely onerous when rates do begin to normalise… Sadly, we have in the making, at least for a proportion of households, the next credit crunch.”

Clearly, that’s the last thing that Osborne wants to see before the election. Rising mortgage rates are already starting to hinder the housing recovery in the US, and their rally began from far more affordable levels than we have ever reached in this country. So make no mistake, low rates are what Carney will strive for.

Maradona stumbles

But that assumes that Carney has a free rein over setting rates, when the fact is, he doesn’t. Since May, when the Federal Reserve in the US started to ponder aloud about easing up on the amount of money it’s currently printing, global bond markets have started to price in higher interest rates, despite the protestations of central bankers.

The truth is that central banks have already ‘lost control’ over the markets, if they ever had any in the first place. Last month, Carney told investors point blank that they were wrong to be pricing in any interest rate rises before the end of 2016. Rather than take him at his word, they promptly started to price in rate rises even earlier – they expect to see a first hike by the middle of 2015.

Now, central bankers can be quite tricky sometimes – Mervyn King always loved to compare himself to star football tactician Diego Maradona, although we’re not sure many would agree – but it’s safe to say, this is not the result Carney was hoping for from his much-hyped forward guidance.

Carney’s problem is that he left a couple of hostages to fortune. He said rates would stay on hold until the unemployment rate fell to at least 7%. As far as the bank is concerned, that won’t happen for another three years. Perhaps more importantly, he added another condition to the mix – that the bank would have to consider acting if it expected inflation to rise above 2.5% over the next 18-24 months.

The trouble is, the bank’s forecasting abilities have been woeful in the past when it comes to predicting the path of inflation. And that’s what left markets thoroughly unconvinced that Carney will be able to keep rates on hold for as long as he hoped. At a speech in Nottingham this week, he tried to add a bit of leeway, pointing out that these are all ‘thresholds’ rather than ‘triggers’ for higher rates. But the fact remains – the stronger the economic data become, the more pressure Carney will fall under to do the one thing that would more than likely derail the recovery – raise rates.

That’s why if there’s one thing we’d bet on, it’s that he will do his best to avoid raising raise rates on this side of the election, regardless of how strong the economic data become.

That may or may not stretch as far as pushing for more quantitative easing (QE), depending on how much further gilt yields rise – but in his Nottingham speech, he pointed out that if rising rates threaten the recovery, then the Monetary Policy Committee “will consider carefully whether, and how best, to stimulate the recovery further”.

Three key lessons for investors

After all, this credit-fuelled recovery is fundamentally what Osborne agreed to pay Carney so much money to deliver. This in turn has at least three major implications for British investors on this side of the 2015 election.

Firstly, we can expect inflation to remain stubbornly above target. It’s already sitting at an annual rate of 2.8%, and surging oil prices won’t bring that any lower. But you can expect the bank to continue making excuses as to why it’s not raising rates to combat this – in his speech, Carney even extended his sympathies to savers. So it’ll be more important than ever to focus on getting ‘real’ (after-inflation) returns on your investments.

Secondly, sterling is likely to be among the weaker developed-world currencies in the longer run. The pound has rallied from its pre-Carney lows, as economic data have improved. But as markets start to realise that Carney has no intention of raising interest rates, regardless of how strong growth gets, the pound is likely to lose that upward momentum. That points to keeping your portfolio diversified internationally. And hang on to gold – as we’ve been saying for a long time, it’s important portfolio insurance, so have 5%-10% in your portfolio. As its recent rise shows, we’re not out of the woods yet, not by a long chalk.

Thirdly – and most importantly for investors on this side of the election – asset prices in the UK will be kept afloat by the ongoing availabilityof cheap money. As well as making it clear that he will act if the market drives interest rates too high, Carney also announced this week that he’s making the capital rules less stringent for the UK’s banks – in other words, he’s making it easier for them to lend.

In short, this recovery isn’t about Britain finding a more sustainable business model. It’s about patching over the yawning cracks in the economy by pumping it full of cheap money in time for the next election in 2015.

If the coalition plan works, and the government – or the Conservatives – manage to win the next election, they may well live to regret it. It’s one thing to suppress interest rates when inflation is still below 3%, but keeping rates low when inflation is starting to hit the headlines will be far harder.

Below, we look at ways to profit from the cyclical recovery. But we also have a few tips for the longer run, when things won’t be looking so pretty.

The investments to buy now

The most obvious beneficiary of the government’s pre-election decision to ‘go for broke’ is the housing market, and companies related to it. While many of the most obvious plays on the housing-sector rally have gone up rapidly, with a second phase of the Help-to-Buy scheme waiting in the wings from the start of next year, we suspect that there’s life in the rally yet. My colleague Phil Oakley has tipped a number of plays in this area, including the housebuilders, in recent months. This week he updates on upmarket cooker manufacturer Aga.

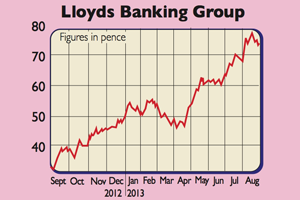

Several other companies are well placed to benefit from any recovery in the property market – more house moves means more changing of fixtures and fittings (new bathrooms and new kitchens, for example) – but one of the most obvious plays is in the banking sector. Lloyds Banking Group (LSE: LLOY) is hugely exposed to the British property market. It’s also being spruced up for a very public return to the stockmarket, again ideally ahead of the 2015 election. The government will do everything in its power to push up the share price of this particular bank – so if you’re looking for a way to play the sugar-rush recovery, this is an easy way to do it.

For broader exposure to the UK domestic economy, you’re better off focusing on mid-cap stocks in the FTSE 250, rather than the more globally-oriented FTSE 100. One simple, cheap way to get exposure to the index is via the iShares FTSE 250 (LSE: MIDD) exchange-traded fund (ETF). The ETF has a total expense ratio (TER) of 0.4%. It also pays a dividend yield of around 1.8%. You could also opt for smaller company stocks – my colleague David C Stevenson ran through the options in MoneyWeek earlier this month. He favours the BlackRock Smaller Companies Trust (LSE: BRSC), the Henderson Smaller Companies Trust (LSE: HSL), and Standard Life UK Smaller Companies (LSE: SLS).

What about the longer run? One business sector should do well from a weaker pound, a poorer UK workforce, and a relative decline in Britain compared to more rapid-growing economies – and that’s tourism. As my colleague Matthew Partridge noted in our free daily email Money Morning, occupancy rates in British hotels are up sharply this year because of the number of people taking ‘staycations’. However, it’s also because, as emerging-market consumers grow ever more wealthy, they are taking more holidays abroad.

A weaker pound will only make Britain – with its wealth of tourist attractions – more attractive. One option to play this is PPHE Hotel Group (LSE: PPH) a fast-growing hotel stock trading on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio of around seven, and yielding around 4%. We’d continue to avoid UK government debt (gilts). The gilt market is likely to be the subject of a tug-of-war between investors and the central bank over the coming years, but it seems likely that yields have seen their lowest point (and therefore, prices their highest point) for a long time to come.

However, index-linked gilts (on which the return is linked to the inflation rate) look like they might be worth tucking away here. ‘Linkers’ have had a difficult year, falling in price during the last few months, as markets start to assume that higher rates will lead to lower inflation in the future. But if the Bank of England fails to tackle inflation, or takes its time in doing so, then eventually prices will rise more rapidly than anyone currently expects.

Roughly speaking, at current levels, inflation needs to average around 3% over the next ten years for linkers to ‘break even’. If you think inflation will average above that (or that markets will start to worry that it will) then linkers are worth buying. You can buy in via the Vanguard UK Inflation Linked Gilt Index fund, which tracks an underlying Barclays Capital index, and charges 0.15% a year.

• Stay up to date with MoneyWeek: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+