Expanding waistlines are a global health epidemic. Smart investors should fill their boots with the firms that will profit, says Matthew Partridge.

It’s no secret that waistlines around the world are expanding. Here at MoneyWeek, we’ve written about the global obesity ‘epidemic’ on several occasions over the past decade or so, and health officials have been fretting about the long-term costs of increasingly hefty populations since at least the 1980s.

Indeed, in America obesity was described by some researchers as the country’s top public health problem as far back as the early 1950s. But it’s one thing to identify a problem and quite another to address it.

If the ‘war’ on obesity has become increasingly strident and high-profile in recent years (take current attempts to equate sugar with tobacco, for example), it’s for a simple reason: the statistics are quite staggeringly grim.

Anyone with a body mass index (BMI – a rough and ready measure that compares an individual’s weight to their height) of over 30 is considered obese. In America in the early 1960s, one in eight adults in the country was obese. Now it’s one in three, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the US national public-health institute.

And of the remaining two-thirds of the population, many are on the road to obesity. If your BMI is above 25, you are considered overweight – a full 70% of Americans fall in to one or the other of the two categories.

In Britain, the problem has reached similar proportions. In 1967, fewer than 2% of Britons were obese. By 2010 about a quarter of the population fitted that description, according to research by the Change4Life campaign.

More recent research by Public Health England, a government agency, found that 64% of English adults are overweight, with the northeast of England hardest-hit (68% are overweight) and London the least (57%).

The National Obesity Forum, a group of professionals who campaign on the issue, now believes that a government projection made in 2007 by the Foresight think tank – that half of Britons could be obese by 2050 – now looks conservative.

And this isn’t just an Anglo-Saxon problem. French Women Don’t Get Fat might have been a bestseller in 2004, but the data suggest the title is somewhat out of date. Roughly 15% of the French are now obese, including 35% of those aged between 18 and 24. Italy, meanwhile, has the highest proportion of overweight children in Europe, and is seeing obesity rates increasing by 0.5% a year.

Shocking statistics come from developing countries too. Despite being far poorer than America, Mexico has near-identical obesity rates to its northern neighbour. Similarly, populations in many nations in Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa now look similar to those in Europe in terms of the percentage of overweight and obese people.

Why does this matter? Because, put simply, obesity kills. It is associated with a number of diseases and conditions, from high blood pressure to heart disease to diabetes. A 2009 study published in The Lancet found that obesity could lower lifespans by up to a decade, making it as deadly as smoking.

Former US Surgeon General Richard Carmona has even warned that young people now face “a shorter life expectancy than their parents” because of overeating.

As well as being costly in purely human terms, that makes obesity a huge drain on healthcare systems – and one that cash-strapped governments are therefore keen to tackle. A project tracking the health of people in the Japanese city of Oshaki found that the obese not only died earlier, but incurred higher lifetime medical costs.

In Britain, the latest figures suggest that overeating and poor diet costs the NHS up to £6bn a year, compared to the £2.7bn annual cost of treating smoking-related illnesses. So, we can expect the war on obesity to continue to gain momentum and publicity as governments spend more on public health campaigns.

This can only be good news for companies involved in helping people to lose weight and treating obesity-related problems. Here, we look at three of the sectors best placed to profit.

The hard way – diet and exercise

The straightforward answer to obesity is to exercise more and eat less. Unless you suffer from an underlying medical condition (such as thyroid disease), losing weight should be a matter of cutting the number of calories you take in and increasing the number you burn off.

The problem, of course, is that this is a bit like arguing that the best way to stop smoking is never to put another cigarette in your mouth – it’s easier said than done. Many people need support in their attempts to lose weight.

This is where the dieting industry comes in. The hugely diverse range of diets available – from copying Stone Age eating habits, to the latest craze for on-off fasting – demonstrates both how keen people are to lose weight, and just how tough it can be to find a method that works.

The US remains the biggest market for such products, with a third of the population claiming to be on a diet, but the idea of dieting is spreading across the world, right alongside surging obesity rates.

Weight Watchers opened its first Chinese branch six years ago and has opened several more since. Meanwhile, weight-loss camps (or ‘fat camps’), popular in the US, have also been springing up around China, catering mainly to the millions of obese children.

Another way to cut calorie intake is to reduce the number of calories in otherwise unhealthy foods. One ingredient that has drawn increasingly bad press on this front is sugar. While sugar makes food tastier, it is extremely calorific.

Professor Simon Capewell of Liverpool University has decried its ubiquitous presence in everything from sweets to “enhanced” brands of mineral water, going so far as to describe it as “the new tobacco”.

Health groups have called for manufacturers to reduce sugar levels in food and drinks. On the one hand, this could be bad news for the companies most associated with junk food. But on the other, it provides a powerful selling point for those who are quick enough to adjust to public tastes.

Of course, ‘diet’ drinks aren’t new. Patio (now Diet Pepsi) was launched in 1963, with Diet Coke (the second-biggest selling brand in the US) hitting shelves in 1982.

However, increased awareness of the issue means that sugar substitutes are appearing in a greater range of products. The global sugar substitutes market is estimated to be worth more than $10bn, with sales growing by 4.5% a year.

Some experts argue that these substitutes have a very limited impact on weight gain – the inferior taste means that consumers just eat and drink more to compensate. But recently two potential substitutes, stevia and monk fruit, have generated a huge amount of excitement. While they have a far lower calorie count than sugar, they have a comparable level of sweetness.

They are also derived from plants, rather than being created in a lab, which is an added selling point. Last year, Coca-Cola used stevia to reduce the sugar in its lemonade drink Sprite, cutting the calories per glass by around 30%.

The middle way – pills and surgery

Obesity is – rightly or wrongly – increasingly treated as a medical issue in itself, rather than a lifestyle choice that causes health problems. This medicalisation process has spurred demand for medical treatments: pills and surgery.

Anti-obesity drugs have been viewed as the ‘holy grail’ for drug companies, but while many have tried, none has yet delivered an easy, pain-free way to lose weight.

These drugs tend to work in one of three ways. One option is to raise the body’s metabolism (increasing the rate at which calories are burned off). Another is to suppress appetite (leading to less food being consumed in the first place), or a drug can cut the proportion of food that goes into the bloodstream (and is eventually stored as fat).

But very few such pills are effective over the longer run. Some – such as amphetamines – have been withdrawn in the past due to serious side-effects. And four years ago the US health regulator, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), rejected three drugs: Qnexa, Contrave and Belviq. This has left Roche’s Xenical (orlistat) as the major anti-obesity drug.

But Xenical, which stops the body absorbing fats, frequently leads to upset stomachs. So any new drug that can prove it works without these sorts of side-effects is likely to be very profitable.

The FDA has also come under pressure from politicians and doctors to treat obesity like other high-priority conditions and be less risk-averse in its approach to approvals. As a result, it reversed its decision on Qnexa (now called Qsymia) and Belviq, after their makers presented additional evidence.

Some patients are also turning to surgery. Gastric bands reduce the size of stomachs, while gastric bypasses enable food largely to avoid the stomach completely. These surgeries are risky and involve long stays in hospital, but they tend to be effective, with some patients shedding up to half their body weight. Even when the weight loss is more modest, most patients end up with improved health.

Researchers at Imperial College London recently suggested that up to two million people in Britain alone would benefit from it. A less extreme alternative is a gastric balloon, developed by Obalon Therapeutics.

The balloon is held in a small capsule. After patients swallow it, the capsule dissolves, allowing the balloon to be inflated via a tube. This reduces the space left in the stomach, and eliminates the need for invasive surgery, or even sedation. So far, trials in the UK and US suggest it is both safe and effective.

The last resort – treating the obese

The final (and most expensive) approach is to treat conditions arising from obesity. The two conditions most directly linked to obesity are diabetes and heart disease. A BMI of over 35 (the definition of morbid obesity) increases the risk of developing diabetes by up to 90 times.

So, with obesity rates skyrocketing, and the population getting older (another risk factor for diabetes), the number of cases is soaring. Globally, diabetes is expected to affect 350 million people within 15 years, up from 275 million now.

This means the sums spent on dealing with diabetes will also rise. Transparency Market Research, a research company, estimates that the global market is seeing compound growth of nearly 20% a year. This means $114bn a year will be spent by 2016.

A big chunk of this will go to those who make and distribute associated medical devices, such as blood sugar monitors and insulin pumps. But the market for drugs that can combat the disease is also huge, which is why drugs firms, such as Novo Nordisk, are investing billions in research, and companies are trying out various new treatments, including stem cell therapy.

Being overweight also puts strain on the heart and raises both blood pressure and cholesterol. These are huge markets: blood pressure treatments are worth over $66bn globally, and cholesterol a further $20bn.

For now, the main treatment for high cholesterol is to take statins, which inhibit an enzyme in the liver. However, Canadian biotech company Resverlogix Corp is trialling ‘epigenetic’ drugs, which interact with specific genes in the body to increase the production of HDL (the ‘good’ form of cholesterol).

The six stocks to buy now

Weight Watchers International (NYSE: WTW) is the world’s leading diet firm, running clubs and selling a range of ready meals. It’s had a tough time recently: competition from online rivals has hit sales and forced it to cut earnings forecasts.

But if new management can turn things round, it still has a strong brand and should benefit from further international expansion and the possible launch of products aimed at men.

The recent drop in the share price means it trades at just eight times its Cape (its price/earnings ratio based on ten-year earnings).

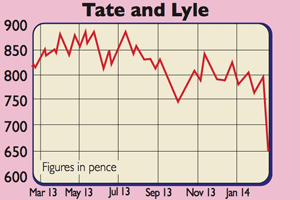

For most of its history Tate & Lyle (LSE: TATE) was one of the world’s best-known sugar firms. But a few years ago it sold its branded sugars to American Sugar Refining, and now focuses on artificial sweeteners and other ‘superfoods’.

Recently the shares took a hit when it warned that Splenda, which accounts for 20% of sales, faces price competition from Chinese producers. But analysts think new products, such as sugar substitutes Tasteva (derived from stevia) and Purefruit (from monk fruit), should more than compensate.

Soda-Lo, its salt substitute, also looks very promising. Tate & Lyle pays a dividend of 4% and trades at 11.5 times 2015 earnings.

On the surgery side, the top maker of gastric bands, with just under a third of the US market, is Allergan (NYSE: AGN). It also markets gastric balloons under the name of Orbera, which deliver major weight-loss benefits without the need for major surgery. Its other products include Botox and anti-glaucoma drugs.

Analysts expect double-digit earnings growth for the next few years, so its p/e (price-to-earnings) ratio is set to fall from its current level of 27, to 20 next year and 16 by 2017.

Vivus (Nasdaq: VVUS) has benefited from the US regulator’s decision to reverse its position on weight-loss drug Qsymia (previously Qnexa). JP Morgan reckons annual sales of Qsymia could hit $835m by 2019.

While sales of Qsymia and royalties from anti-impotence drug Stendra are Vivus’s sole source of income, it has drugs in the pipeline focused on sleep and female sexual dysfunction.

In the short term, it’s set to spend a large sum on research and building its network of sales reps. But it has a large cash reserve and trades at five times 2017 earnings.

The market leader in diabetes treatments is Danish company Novo Nordisk (NYSE: NVO), favoured by Research Investments newsletter writer Dr Mike Tubbs.

Recent innovations include the NovoFine Plus diabetes pen, which makes insulin injections less uncomfortable, and reduces breakages. It continues to benefit from strong double-digit growth at its insulin division and has a strong pipeline, including obesity treatment liraglutide (based on its blood sugar drug Victoza), which may be approved by the US regulator later this year.

A high-risk option is Canadian biotech Resverlogix Corp. (Toronto: RVX). Second-stage trials of its epigenetic cholesterol drug RVX-208 were disappointing, hammering the share price last summer. But subsequent analysis of the data showed it was far more effective when used along with another treatment, reducing the number of ‘major adverse cardiac events’ in high-risk patients.

The company is now raising more money to conduct further trials. There are also hopes that RVX-208 could be used as a treatment for diabetes.