What’s happened?

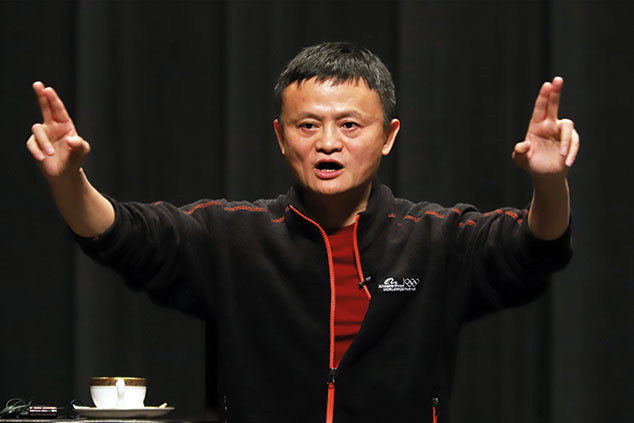

Jack Ma, the richest man in China and founder of the e-commerce giant Alibaba, has put the issue of long working hours in the spotlight with his contentious claim that China’s “996” culture of extremely long working hours is “not a problem”, but rather a “blessing”.

The “996” refers to the practice of working 12-hour days (from 9am to 9pm) on six days a week. Such long hours are common among China’s army of software developers (among many other classes of worker) and they are getting very irritated about it. In late March a group of anonymous developers used GitHub (the world’s largest host of source-code, which Beijing can’t readily censor because it’s so useful to Chinese techies) to launch an anti-996 campaign.

The developers have named and shamed big tech firms that force workers to put in excessive hours that leave them exhausted and unproductive – or, as Ma would have it, properly committed to the “happiness and rewards of hard work”.

But aren’t we working fewer hours than we used to?

Yes, that’s the trend. John Maynard Keynes famously predicted in his 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” that technological advances would free us from toil such that a century on (by 2030) we might each be working no more than 15 hours a week. Similarly, his near-contemporary

Bertrand Russell reckoned that if work were shared out equally the average working day would need to be just four hours. In his 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness” the great philosopher wrote that such a well-organised, short working day would “entitle a man to the necessities and elementary comforts of life” – leaving the rest of his day free for science, painting, writing and so on.

The result, he thought, would be a guarantee of “happiness and joy of life, instead of frayed nerves, weariness and dyspepsia”. (He didn’t mention too much about who would be looking after the children or cleaning the bathroom.)

So how close have we got?

We might not have quite entered the Keynes-Russell nirvana, but we are working about half the number of hours of 150 years ago, and significantly fewer than 50 years ago (when we worked about 40 hours a week on average).

In the late 19th century, workers in industrialised countries such as Britain generally worked 60 or 70 hours a week, or more than 3,000 hours a year – in Jack Ma’s 996 territory. But a consistent long-term trend is that as economies get richer, people tend to work fewer hours. (That remains true of the UK, even though in the first half of this decade working hours ticked up, by about 3%, as the economy recovered from the financial crisis and recession.)

In the most recent year for which the OECD club of developed nations has compiled figures (2017), the average Briton spent 1,514 hours at work. Assuming weekends off plus 28 days paid holiday a year, that’s the equivalent of a 32.6 hour working week. Looked at another way, it’s equal to four working days of a length that Jack Ma would view as laughably lightweight (9am to 6pm with almost an hour for lunch).

How do we compare internationally?

We’re moderate slackers, but not outrageously lazy. Of the 36 industrialised nations surveyed by the OECD, the number of hours worked by an average worker in the UK is a quarter of the way along the range from low to high. The average for the OECD nations as a whole is 1,744 (a 37.6-hour week); both Japan and the US are pretty close to this figure.

The hardest workers are in Mexico (2,257 hours), followed by South Korea, Chile, Greece and Israel. The figure in France is exactly the same as in the UK, while the supposedly less work-inclined southern Europeans – in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, as well as Greece – all work significantly longer hours than we do.

By contrast, the biggest slackers are all in well-off northern Europe: Denmark, Norway, Netherlands, Sweden and Iceland all work a bit less than we do. And bringing up the rear, working a pleasantly relaxed 1,356 hours per year, are the Germans.

But aren’t the Germans famously hard-working?

No, they are famously productive. The OECD data highlights a striking inverse correlation: as the number of working hours in a country rises, the labour output per worker-hour tends to fall. Germany is at the extreme end of that spectrum. A similar phenomenon is seen on the micro-level of the individual. A raft of academic studies has found that, after a certain point, working long hours is counter-productive in terms of productivity and performance.

This tipping point varies between 40 and 50 hours a week, and is hit earlier when the work includes long shifts of 12 hours or more. And at 48 hours a worker’s output drops sharply, according to one recent Stanford study.

What about health impacts?

Equally, a vast body of academic research (for example, a 2004 meta-survey of the literature by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) has found that working long hours (more than 40 hours a week) is associated with poorer health outcomes. These include weight gain, higher consumption of alcohol and tobacco, higher risk of heart disease and stroke, and more work injuries.

There’s nothing new about the realisation that working too hard is bad for you, of course. Adam Smith himself noted that the “man who works so moderately as to be able to work constantly, not only preserves his health the longest, but in the course of the year, executes the greatest quantity of works”.